"History through The Korea Herald” revisits significant events and issues over the seven decades through articles, photos and editorial pieces published in the Herald and retell them from a contemporary perspective. – Ed.

|

South Korean officials inspect the bodies of North Korean commandos who sneaked into South Korea on a mission to assassinate then-President Park Chung-hee. (National Archives of Korea) |

It was one of the most daring infiltrations by North Koreans into South Korea after the war of 1950-53 -- 31 commandos on a mission to break into the presidential office in Seoul and assassinate then President Park Chung-hee.

On the night of Jan. 21, 1968, a team of 31 armed North Korean guerrillas arrived in the mountains near Cheong Wa Dae, four days after crossing the Military Demarcation Line on foot.

When stopped by police at a checkpoint near Jahamun, Jongno-gu, the North Koreans -- donning South Korean army uniforms -- said they were counterespionage agents and refused to show their IDs.

Upon receiving a report on the suspicious group, the chief of Jongno Police Station went out in a jeep to challenge them. The commandos shot him and his driver.

The commandos also threw a grenade at a passing bus full of civilians, and exchanged fire with the South Korean police and military.

In the dayslong chase that followed, 29 of the North Koreans were killed, one was captured alive and one was assumed to have fled to the North.

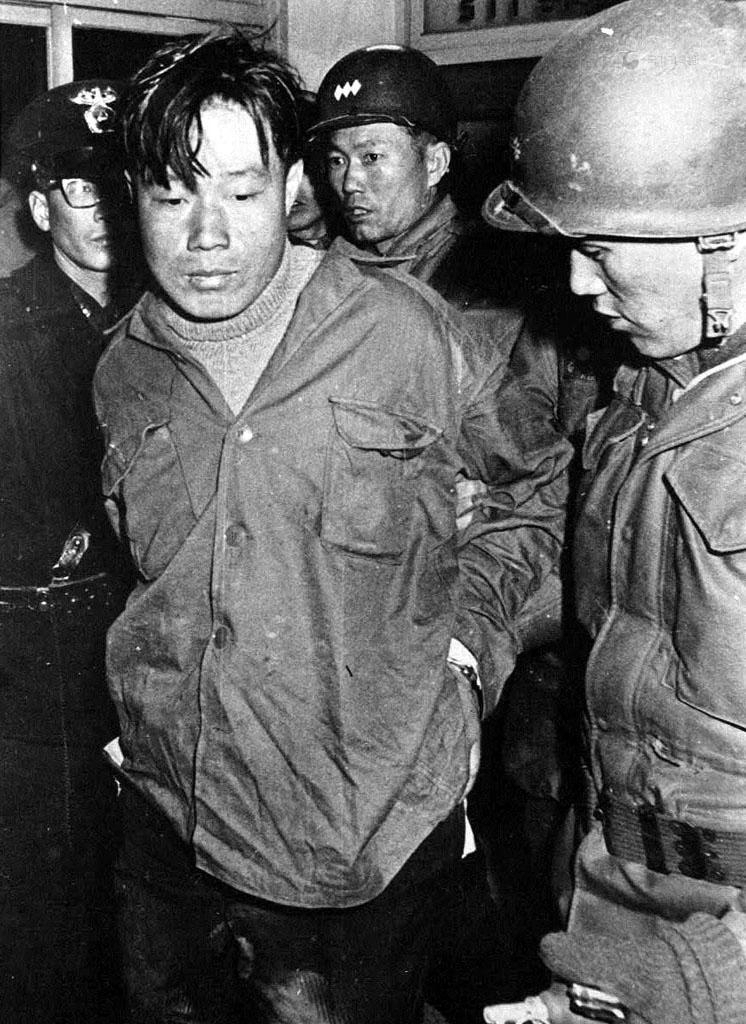

The captive, 25-year-old Kim Sin-jo, ended up changing his allegiance to South Korea and later became a Protestant pastor there.The number of South Korean casualties varies according to different sources, but about 23 soldiers and policemen and seven civilians were killed, including a 15-year-old boy on the bus and the district police chief. Between 50 to 60 South Koreans were injured.

The Jan. 23, 1968 issue of The Korea Herald carried several related articles on the front page under the headline “31 red agents intercepted in Seoul.”

|

The Jan. 23, 1968 edition of The Korea Herald |

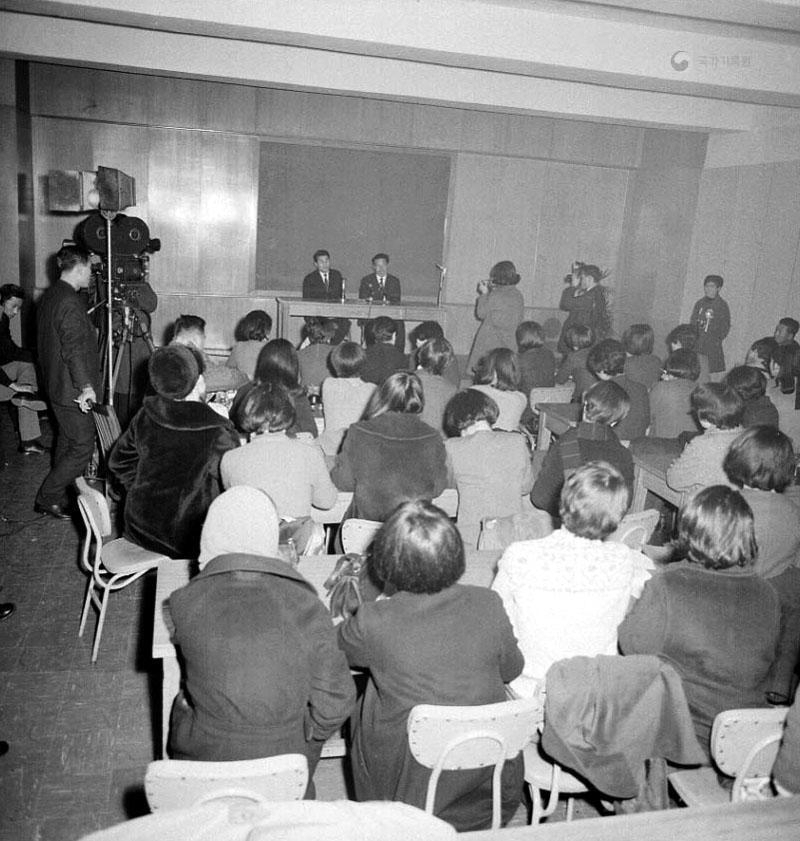

Kim told a press conference at the Republic of Korea Army Counter Intelligence Corps that the armed agents were organized into a “suicide team” to attack the presidential mansion late Sunday night or early Monday morning, according to an article titled “Cheong Wa Dae target of North Korean agents.”

|

North Korean infiltrator Kim Sin-jo was captured alive and later defected to the South. This photo shows Kim being escorted from a police station on Jan. 22, 1968. (National Archives of Korea) |

Kim identified himself as a second lieutenant of the 124th North Korean People’s Army.

“Commanded by a North Korean army captain, each of the 31 agents organized into six groups were armed with an automatic rifle, a Russian-made pistol, eight hand grenades and an antitank grenade,” the article reads.

“Kim said the first suicide group was given the mission to attack the second floor of the presidential mansion, the second group the first floor, and the third group the office of the presidential bodyguards.”

The fourth group was supposed to attack the office of the presidential secretaries and the fifth group was to kill sentries manning the entrance to Cheong Wa Dae and the main presidential mansion.

A sixth group, consisting of drivers, was to storm the motor pool to steal cars for the ride back to Munsan, and then cross the Imjin River to the North, Kim was quoted as saying.

|

Kim Sin-jo attends a press conference, which was broadcast live on TV. (National Archives of Korea) |

“He said the armed Communist marauders were trained for two years at the 124th North Korean People’s Army with the assigned mission of overthrowing the ROK government,” the article reads.

“He said about 2,400 selected North Korean army soldiers were currently receiving guerilla-type training … for more massive attacks on ROK government offices and industrial facilities.”

Born in Chongjin, North Hamgyong Province, Kim said his parents and three sisters lived in his hometown, and that his parents were working in a textile factory in Chongjin.

After crossing the MDL on the night of Jan. 17, the 31 commandos had camped their first night in the South at a US military zone on the western front. They crossed the frozen Injin River on the evening of Jan. 18 and then camped the second night in a mountain in Paju, Gyeonggi Province before marching through the mountains toward Seoul.

According to a New York Times article dated Feb. 18, 1968, on their first day in the South “the south-bound commandos had come upon four woodcutters, who were taken prisoner for five hours and then released with the warning that they and their families and their village would be annihilated if they told the police.”

Despite these threats, the woodcutters ended up reporting them to the police.

Impact and aftermath

That North Korean infiltrators reached to within 300 meters of the presidential residence came as a shock to the Park Chung-hee regime, and led to a flurry of measures to bolster the South’s readiness for such attacks.

One of the most immediate actions taken was the extension of mandatory military service by six months to 36 months for the Army and the Marines. It was also increased by three months to 39 months for the Navy and the Air Force, shifting from a previous policy of reducing the service term.

According to "Korean Contemporary History Walk," written and compiled by renowned media and communications professor Kang Jun-man, the incident also nudged the Park administration to speed up its launch of homeland reserve forces in April that year; issue resident registration numbers and cards for all South Koreans aged 18 and up in November the same year; and beef up anti-Communist campaigns.

Barbed wire was installed at the MDL and civilian access was blocked from the route that Kim and his team took in Bukaksan north of Cheong Wa Dae until it was reopened in April last year.

Just two days after the North Koreans’ shocking incursion into the heart of Seoul, North Korean forces attacked and captured the USS Pueblo, an environmental research ship attached to the US Navy intelligence as a spy ship.

North Korea stated that the ship intentionally entered their territorial waters 14 kilometers away from Ryo Island, but the US maintains that it was in international waters when it was attacked.

The Feb. 18 New York Times article reads, “Seoul waited for the US to show its anger and indignation at these affronts to its ally and itself. But the American response was not one to provide much comfort.”

The commando attack on Park was “virtually ignored,” it said, adding that “the taking of the spy ship inspired US anger, then some mumbles about measures to get it back, finally an American contact with North Korea through the Panmunjom armistice machinery to negotiate the return of the Pueblo’s crew.”

As retribution for the Jan. 21 incident, South Korea began training its own squad of killers called Unit 684 later that year on Silmido, an uninhabited island near Incheon, to infiltrate North Korea and kill its then leader Kim Il-sung.

However, the assassination mission was canceled, as Unit 684 members revolted on Aug. 23, 1971. They killed most of the guards on the island and went into the mainland via boat, where they hijacked a bus to Seoul.

The bus was stopped by the army in Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul, and 20 of the Unit members on board were shot or committed suicide with hand grenades.

The four survivors were sentenced to death by a military tribunal and executed in 1972. The story was made into the 2003 film "Silmido," which was a critical and box office success.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)