The idea of a “fatherland” is not much thought or talked about, as it seems so obvious. But for many ethnic Korean residents of Japan, the yearning for the “fatherland” remains, as they strive to maintain their identity as Koreans.

A documentary depicting ethnic Koreans in Japan who say their hometowns are in South Korea, but believe their fatherland is North Korea, was screened in Seoul as part of a three-day event starting Friday. Park Yeong-i, director of “The Sky Blue Symphony,” expressed hopes for better relationships between the ethnic Koreans in Japan and the two Koreas, during his visit here.

|

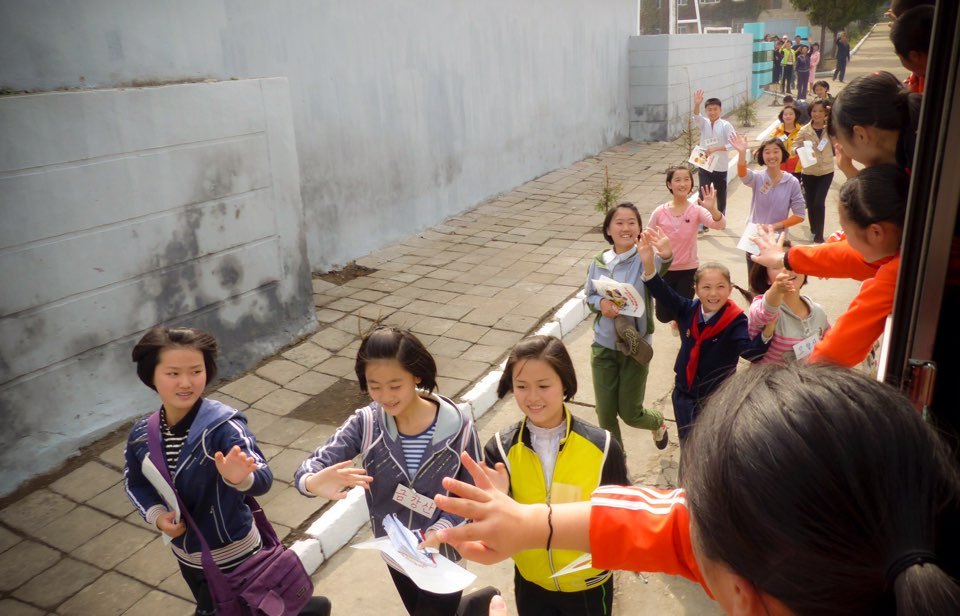

North Korean students bid farewell to ethnic Korean students living in Japan as they leave North Korea. (Park Yeong-i) |

This group, known as zainichi in Japanese, consists of Koreans who moved to Japan mostly during the early 1900s before the Korean Peninsula was split into South and North at the end of World War II. They have often been victims of discrimination in Japan, with their ambiguous status not protected by South Korea or North Korea.

They have fought to gain a foothold in mainstream Japanese society, but the zainichi are still left out in many ways. Almost seven decades have passed since the end of the Korean War (1950-53) and these ethnic Koreans continue to strive for protections that no country guarantees them.

The documentary, first released in 2016, drew tears from the South Korean audience on Friday, as it showed the struggles of ethnic Korean students in Japan to find their true identity.

Zainichi and North Korea

In the documentary, the students are asked where their families came from. They give names of cities in South Korea, such as Jeju. But when they are asked where their fatherland is in their hearts, they answer, “North Korea.”

According to Park, about 90 percent of the zainichi came from the southern part of the Korean Peninsula. But because North Korea supported the community from early on, it was natural for the zainichi to feel closer to the communist country than South Korea.

During the Japanese colonial period from 1910 to 1945, ethnic Koreans in Japan were Japanese nationals. After Korea was liberated in 1945, those wishing to stay were given the status “Joseonjeok,” meaning they were from the Korean Peninsula. Joseon referred to the entire Korean Peninsula at the time.

Two separate governments came to power in the southern and northern parts of the Korean Peninsula divided by the 38th parallel, following separate elections in the southern part occupied by the US military and the northern part occupied by Soviet forces.

When the 1950-53 Korean War ended in an armistice, the Korean Peninsula was no longer one country that ethnic Koreans could call a fatherland.

Since then, they have sought to maintain their Korean cultural heritage, building their community and establishing Joseon schools to provide “nationalistic education.”

It was North Korea that came to the assistance of the Joseonjeok in Japan when they were living lives of hardship.

In 1957, Pyongyang sent 120 million yen ($1.12 million) to the schools, which Park explains would be worth about $17 million today.

|

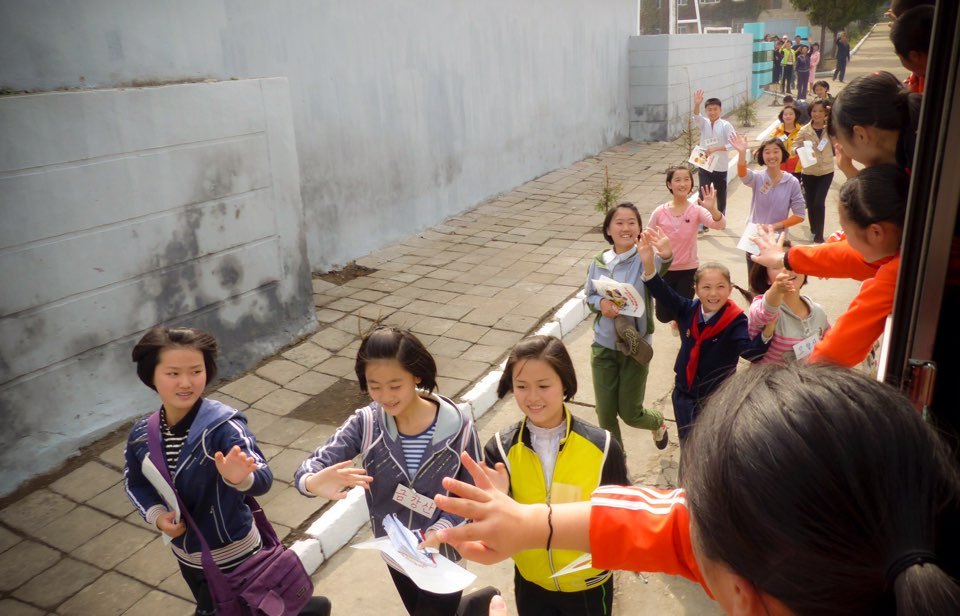

An ethnic Korean student cheers in front of the crater on Paektusan. (Park Yeong-i) |

“There is a well-known saying. Kim Il-sung said even if they are on a tight budget and cannot build one or two more factories, the country should still support the overseas Koreans,” Park said, referring to the founder of North Korea.

“So, it is obvious that we feel closer to North Korea than the South.”

Across Japan, 8,000 students attend 64 Joseon schools. All Joseon students visit North Korea for their graduation field trip. The documentary follows 11 senior students from the Ibaraki Joseon School who travel to North Korea, visiting Pyongyang, Paektusan and other historic sites.

Keeping their identity as Koreans

The zainichi have struggled to earn their rights as residents and citizens in Japan. One battle they are fighting is to obtain equal rights for zainichi students. The Japanese government provides tuition support to all high school students, but Joseon schools are excluded.

Tuition at Joseon schools is not cheap. According to Park, it costs an average of about 400,000 won per month.

Japanese law also does not recognize Joseon school diplomas, and their graduates are ineligible to sit university entrance exams. These students can be admitted to university under a separate system, implemented by the universities.

The majority of zainichi have obtained South Korean nationality, but some have chosen to remain Joseonjeok -- which is not a nationality, but a mere status. Still, Joseonjeok can apply for visas to travel outside of Japan and are given special permanent resident permits.

They can also visit both North and South Korea, because of their special status.

“My nationality is South Korean. But I am still trying to find what is the fatherland to me,” Park said.

Park, a third-generation zainichi, explained that it was not strange for him and those older them him to harbor hostility toward South Korea and Japan. Sentiment toward South Korea, however, is changing nowadays, because South Korea is paying closer attention to the zainichi and providing more support. K-pop culture has also had an impact on the younger generation.

A South Korean civic group called Mongdang Pencil: People Working with Korean Schools has also played a role in changing the minds of the zainichi.

The group was established in 2011, first as part of the effort to help the people there when a magnitude 9 earthquake hit the Pacific coast of Tohoku in Japan, causing a massive tsunami.

Park, who also graduated from a Joseon school and a Joseon university, started his film career at age 30, influenced by Kim Myeong-joon, who directed “Our School,” a film about the zainichi, in 2007. Kim is the secretary-general of Mongdang Pencil: People Working with Korean Schools.

The scenes in which the students visit North Korea were all filmed by the students, as South Korean film directors were not allowed to enter the country.

Kim encouraged Park to make the documentary, saying it would be meaningful for ethnic Koreans in Japan to be able to make their voices heard via film.

Stereotypes about North Korea

The lively scenes in the documentary provide a peek into the everyday lives of North Koreans, making viewers rethink their attitudes about the people there. The documentary, while it avoids praising the communist regime, highlights the more human side of life in North Korea -- the easygoing music teacher making jokes and supportive adults who encourage students.

|

Director Park Yeong-i (Courtesy of Park Yeong-i) |

Park, who has made about 20 visits to North Korea, raised concerns that the outside world is looking at North Korea with jaundiced eyes. Regardless of politics, people are the same, he said.

When asked about the recent reports highlighting the dire food situation in North Korea, based on his latest visit to the country’s rural areas from late May to early June, Park said it is not as bad as has been reported.

“Of course, there are still many who are in difficult situations, but it is not like a life-or-death struggle,” Park said.

“In Pyongyang, interest in health has risen and there are so many products related to healthy diets now.”

Park also pointed out that South Korean and other foreign media are far from objective in their depictions of North Korea, grossly overemphasizing the negative aspects.

“You should look at how information is provided to media outlets. For example, it is highly likely that the informants in North Korea will say negative things about the regime and get paid. Those stories sell better,” Park said.

He also denied a recent news report from a South Korean daily that North Korea’s Mass Games -- a coordinated gymnastics and artistic performance -- had stopped due to a food shortage. While it is true that the exercises were suspended for some time, that was because North Korean leader Kim Jong-un had ordered changes to the program, Park said.

The Mass Games resumed in their new format on June 20, when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Pyongyang.

By Jo He-rim (

herim@heraldcorp.com)