|

A currency dealer at KEB Hana Bank in Seoul looks at computer monitors during a lunch break on March 13, when the US dollar hovered around 1,218 won and the Kospi plunged to close under 1,800 points. (Yonhap) |

SEJONG -- A country’s interest rate generally determines the value of its currency, although this formula may not be applicable to safe havens such as the US dollar, the euro, the British pound and the Japanese yen.

For an emerging country whose currency depends on reserve currencies like the dollar, a low interest rate incurs an outflow of foreign capital as the currency becomes less attractive to investors. Capital flight results in a cheap local currency.

Over the past few years, South Korea’s central bank has seemingly tolerated capital outflow by keeping the benchmark rate under 2 percent for five years starting March 12, 2015.

On Monday, the Bank of Korea further cut the rate by 0.5 percentage point from its former low of 1.25 percent per annum to a fresh all-time low of 0.75 percent.

The monetary easing action, carried out by seven rate setters on the BOK’s Monetary Policy Committee, may have been an unavoidable emergency measure to prop up the economy in the face of COVID-19.

But the BOK’s actions stand in sharp contrast with those of the US Federal Reserve, which has also cut its rates twice -- first by 0.5 percentage point on March 3 and then by 1 percentage point on March 15, to the range of 0-0.25 percent.

For several years, the US continually hiked its rates in anticipation of unforeseeable shocks that might force eventual rate cuts. During the first half of 2019, the Fed’s rate reached 2.25-2.5 percent.

On the contrary, Korea has maintained low rates for years. BOK Gov. Lee Ju-yeol and his six colleagues were tightfisted in their resistance to preparing for a worst-case scenario caused by negative external factors such as a natural disaster.

As a result, a number of capital market participants and research analysts have cast doubt on the efficacy of Monday’s rate cut.

Capital market indices are heralding the further weakening of the Korean won, which has already lost ground to major currencies, including reserve currencies.

|

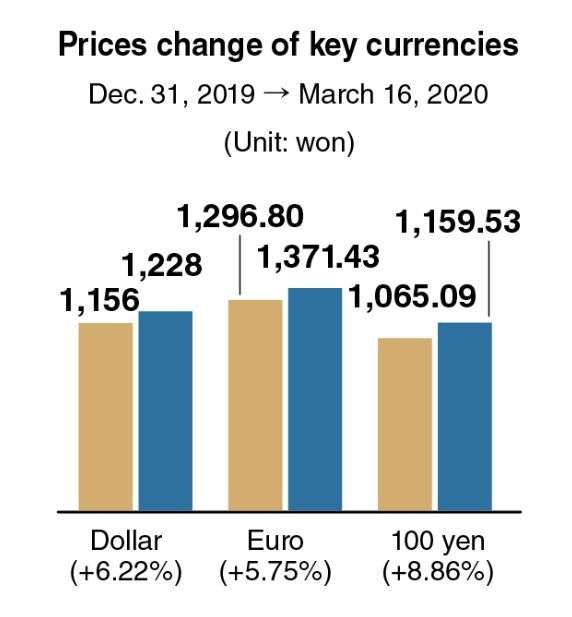

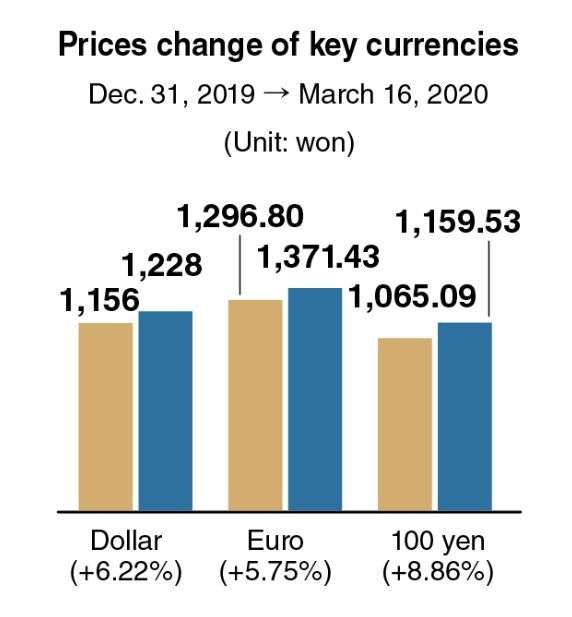

(Graphic by Kim Sun-young/The Korea Herald) |

Compared with the last trading session of 2019, the US dollar had climbed 72 won (6.22 percent) to trade at 1,228 won as of Monday.

The euro, which stood at 1,296.80 won on Dec. 31, had risen 74.63 won (5.75 percent) to 1,371.43 won.

The Japanese currency surged by 94.44 won (8.86 percent) over the same period, from 1,065.09 won per 100 yen to 1,159.53 won.

“Despite the quantitative easing involving the drastic lowering of the benchmark rate in the US, investors would ultimately choose safe assets amid uncertainty from the novel coronavirus,” an analyst in Yeouido said. “In the coming trading sessions or weeks, the value of the won against the dollar may reach its weakest level in about 10 years.”

He also said “the cheap won (or low purchasing power) also means Korea cannot benefit from the low-priced international crude products, which are traded with the greenback.”

West Texas Intermediate, which was priced at $61.06 per barrel on Dec. 31, 2019, has traded under $35 since the second week of March.

There had been a series of calls from some local market insiders for the BOK to raise the interest rate. They warned of record-high household debt and instability in exchange rates.

While the US and some major economies were normalizing their interest rates through rate hikes, Korea’s central bank has played a significant role in attracting huge amounts of capital to the real estate sector since 2014, when the key rate began its long fall from 2.5 percent per annum.

The new coronavirus is dealing a serious blow to China, Korea and the entire world. But the Korean won has been hit worst among the major currencies, including the Chinese yuan.

The yuan hovers around 175 won, up more than 5 percent from the last session of 2019, when it stood at 166.04 won.

Korean households are expected to reduce consumption due to low purchasing power, and businesses could face a heavier burden in terms of raw material procurement.

The won’s weak position could benefit exporters. But economists say that price competiveness in outbound shipments is meaningless when the currency depreciates to such abnormally low levels.

By Kim Yon-se (

kys@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Health and care] Getting cancer young: Why cancer isn’t just an older person’s battle](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050043_0.jpg)