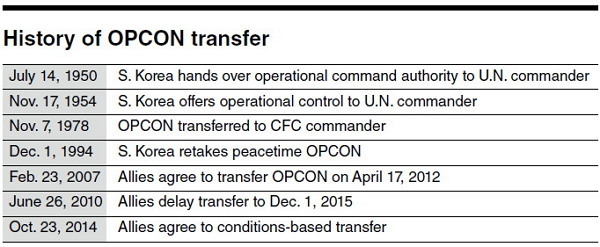

In 2007, the allies first agreed to make the OPCON transfer on April 17, 2012 ― the reverse of 7.14 ― the date when South Korea’s President Syngman Rhee gave his “command authority” to U.N. Commander Gen. Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War in 1950.

At the time, the liberal Roh Moo-hyun administration hoped to bring wartime operational control back to Korea, as it pushed to enhance Korea’s military self-reliance and “balance” the nation’s alliance with the U.S.

Washington, at the time, was in the process of a global troop realignment following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack in 2001.

After the bilateral agreement on the transfer, the allies shared a positive outlook for peninsular security. Thanks to reduced cross-border tensions during the two liberal South Korean governments that pushed for generous engagement with Pyongyang, the security environment was perceived as fairly stable.

But a series of North Korean provocations had led Seoul and Washington to reconsider the timing of the OPCON transfer. In April 2009, the North launched a long-range rocket. A month later, it conducted a second nuclear test. In March 2010, the North torpedoed the South Korean corvette Cheonan, killing 46 sailors.

Against this backdrop, the leaders of the allies agreed in June 2010 to delay the OPCON transfer to Dec. 1, 2015. They concurred that the OPCON transfer in 2012 could embolden an increasingly provocative North Korea and further raise uncertainties in the security landscape here.

Under the “Strategic Alliance 2015” plan, the allies had been preparing for the OPCON transfer based on the mutual agreement that the preparation should proceed in a direction that would strengthen their combined defense posture.

But talk of the need to delay the OPCON transfer resurfaced after the North conducted a third nuclear test in February 2013, some two months after it launched a satellite using rocketry that could be repurposed for use in long-range ballistic missiles.

Concerns rose that Seoul might not be able to acquire the full range of capabilities to lead wartime operations by the end of 2015 in terms of military equipment, strategy and operational experience, given North Korea’s enhanced nuclear and missile capabilities.

To address the concerns, Seoul’s Defense Ministry asked the U.S. last May that the allies rethink the timing of the OPCON transfer in light of the changes in the security conditions on the peninsula.

The ministry claimed that the South needed time to build its capabilities to counter the communist state’s evolving military threats. At the Security Consultative Meeting last year, the allies’ defense ministers shared the need to pursue the transfer based on the security “conditions” rather than on a fixed timetable.

The OPCON transfer has long been a highly divisive issue in South Korea.

Those supporting the transfer say that Seoul needs to reduce its heavy reliance on the U.S. and strengthen its defense capabilities. Some approach the issue from the perspective of national pride.

The proponents also point out that particularly with the intensifying Sino-U.S. rivalry, Seoul needs to improve its independent operational capabilities to ensure that it has strategic leverage with the two great powers.

But opponents of the transfer maintain that Seoul is not yet ready to deal with the unpredictable North, and that relying on the U.S., the world’s strongest military power, is the most cost-effective way to ensure national security.

Some 20 days after the outbreak of the 1950-53 Korean War, President Rhee relinquished operational “command authority” over Korean forces to the U.N. commander. After the war, the U.S. continued to hold the authority.

In November 1954, the allies drew up the “Agreed Minute Relating to Continued Cooperation in Economic and Military Matters,” a document that ensures the U.S. continues to possess “operational control” over South Korean forces.

The U.S., scholars say, wanted to have operation control over Korean troops as President Rhee threatened to “advance into the North and achieve reunification,” a move apparently to pressure the U.S. to delay its troop withdrawal and offer stronger security support.

In 1994, Seoul retook peacetime operational control from Washington in recognition of the need to make the alliance a more complementary partnership instead of relying wholly on the U.S. Washington, then, considered the transfer as it felt the need to reduce overseas American troops following the end of the Cold War.

By Song Sang-ho

(

sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)