|

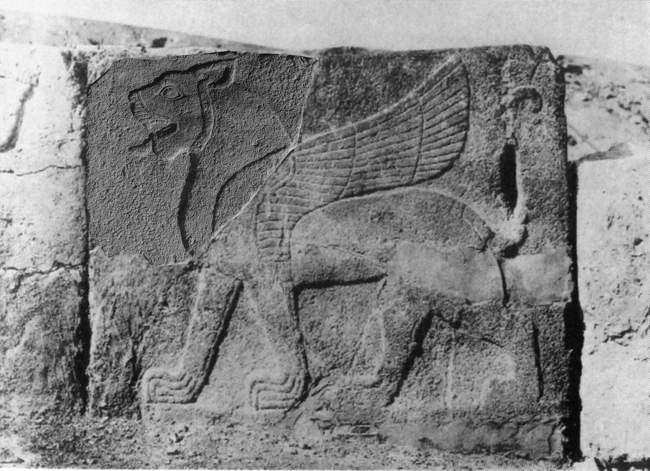

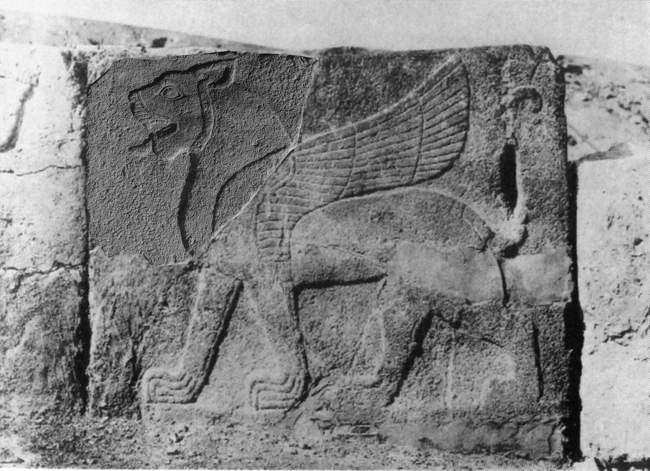

This image made available by the Joint Turco-Italian Archaeological Expedition on Nov. 1 shows a file photo of a reconstruction of the lion head fragment set into the slab now in the Anatolian Civilizations Museum in Ankara, Turkey. (AP-Yonhap News) |

ISTANBUL (AP) ― Few archaeological sites seem as entwined with conflict, ancient and modern, as the city of Karkemish.

The scene of a battle mentioned in the Bible, it lies smack on the border between Turkey and Syria, where civil war rages today. Twenty-first century Turkish sentries occupy an acropolis dating back more than 5,000 years, and the ruins were recently demined. Visible from crumbling, earthen ramparts, a Syrian rebel flag flies in a town that regime forces fled just months ago.

A Turkish-Italian team is conducting the most extensive excavations there in nearly a century, building on the work of British Museum teams that included T.E. Lawrence, the adventurer known as Lawrence of Arabia. The plan is to open the site along the Euphrates river to tourists in late 2014.

The strategic city, its importance long known to scholars because of references in ancient texts, was under the sway of Hittites and other imperial rulers and independent kings. However, archaeological investigation there was halted by World War I, and then by hostilities between Turkish nationalists and French colonizers from Syria who built machine gun nests in its ramparts. Part of the frontier was mined in the 1950s, and in later years, creating deadly obstacles to archaeological inquiry at a site symbolic of modern strife and intrigue.

“All this is very powerfully represented by Karkemish,’’ said Nicolo’ Marchetti, a professor of archaeology and art history of the Ancient Near East at the University of Bologna. He is the project director at Karkemish, where the Turkish military let archaeologists resume work last year for the first time since its troops occupied the site about 90 years ago.

At around the same time, the Syrian uprising against President Bashar Assad was escalating. More than 100,000 Syrian refugees are sheltering in Turkish camps, and cross-border shelling last month sharpened tension between Syria and Turkey, which backs the rebellion along with its Western and Arab allies. Nuh Kocaslan, mayor of the nearby Turkish town of Karkamis, said he hoped the Syrian war would end “as soon as possible so that our region can find calm,’’ and that the area urgently needs revenue from tourists, barred for now from Karkemish because it is designated a military zone.

Archaeologists say they felt secure during a 10-week season of excavation on the Turkish side of Karkemish that ended in late October. One big eruption of gunfire from the Syrian side turned out to be part of a wedding celebration. The team arrived in August, one month after Syrian insurgents ousted troops from the Syrian border town of Jarablous. A Syrian government airstrike near Jarablous killed at least eight people that same month.

About one-third of the 90-hectare archaeological site lies inside Syria and is therefore off-limits; construction and farming in Jarablous have encroached on what was the outer edge of the ancient city. Most discoveries have been made on what is now Turkish territory.

When a British team began work in 1911, the undivided area was part of the weakening Ottoman Empire. Germans nearby were constructing the Berlin-Baghdad railway, which traverses the ancient site along the border. Archaeologist C.L. Woolley and his assistant, Lawrence, found basalt and limestone slabs carved with soldiers, chariots, animals and kings; many are displayed today in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, the Turkish capital.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)