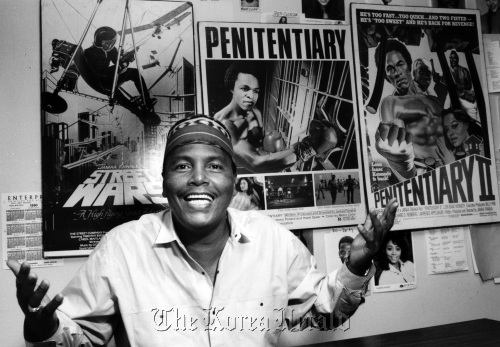

Jamaa Fanaka, who emerged as a dynamic black filmmaker with his gritty independent 1979 film “Penitentiary” and later made headlines with his legal battles alleging widespread discrimination against women and ethnic minorities in the film and television industry, has died. He was 69.

Fanaka was found dead in his apartment in South Los Angeles on Sunday, said his daughter Tracey L. Gordon. The cause of death has not been determined, but she said it probably was the result of complications of diabetes.

The Mississippi-born Fanaka was still enrolled in the UCLA film school when he wrote, produced and directed his first three feature films, financed with competitive academic grants and funds from his parents: “Welcome Home, Brother Charles” (1975), “Emma Mae” (1976) and “Penitentiary,” which was both a critical and box-office success.

In his review of “Penitentiary,” the Los Angeles Times’ Kevin Thomas wrote that Fanaka “has taken one of the movies’ classic myths, the wrongly imprisoned man who fights for his freedom with boxing gloves, and made it a fresh and exciting experience.”

What “Penitentiary” says, Fanaka told the Times in 1980, “is that no matter what kind of situation one is confronted with, within each of us is the wherewithal to triumph.”

Fanaka went on to write, produce and direct two “Penitentiary” sequels, in 1982 and 1987. His sixth and final film was “Street Wars,” a low-budget 1992 action-drama set in South L.A.

|

Jamaa Fanaka, who emerged as a dynamic black filmmaker with his gritty independent 1979 film “Penitentiary” and later made headlines with his legal battles alleging widespread discrimination against women and ethnic minorities in the film and television industry, has died. He was 69. (Los Angeles Times/MCT) |

“It’s kind of a coming-of-age story about a kid trying to decide whether he’s going to become a gangster or lead a normal life, which was basically Jamaa’s choice too,” said Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

“He loved to tell the story about coming out of the Air Force and then hanging around Compton, where he lived, and a friend of his wanting to set up some kind of crime and him seeing a recruiting office for UCLA and walking in there instead,” said Horak.

Fanaka was born Walter Gordon in Jackson, Miss., on Sept. 6, 1942, and moved to Compton with his family when he was 12.

After he transferred to UCLA from Compton College, he changed his name to Jamaa Fanaka, which is based on the Swahili words meaning “together we will find success.”

He graduated summa cum laude from UCLA in 1973 and earned his master’s from the film school in 1979.

Three of Fanaka’s films were screened late last year in “L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema,” a UCLA Film & Television Archive film series featuring movies by African-American and African former students who attended the UCLA film school in the 1970s and early ’80s.

Horak, who was one of the curators of the film series, said Fanaka’s films are “extremely interesting because they navigate a path between basically Hollywood-style filmmaking and independent filmmaking ― very low budget, but at the same time very close to the community. He used amateur actors in secondary roles and shot in the community, and the stories came out of that community.”

One thing Fanaka “complained about a lot is that the ‘Penitentiary’ films ― and even the earlier films ― were picked up by a video distributor and distributed as blaxploitation films,” Horak said.

“He did not like that moniker because he said even though they’re made like blaxploitations ― cheap and all of that ― his goal was not to exploit anyone, and they were a more serious intent than most blaxploitation films.”

Fanaka was the outspoken founder of the Directors Guild of America’s African American Steering Committee.

In 1999, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a District Court’s decision to dismiss Fanaka’s race-discrimination lawsuit suit against the Directors Guild in which he claimed it was part of a “conspiracy” to keep women and minorities out of the industry.

And in 2002, the 9th Circuit upheld a district court decision to dismiss Fanaka’s race discrimination lawsuit filed against the major film studios and networks.

Fanaka continued to feel strongly about the issue, Horak said, “and he was very much an advocate not only for himself but for a younger generation of African-Americans trying to break into the industry.”

Besides his daughter Tracey, Fanaka is survived by his other children, Michael, Katina and Twyla; his parents, Robert Gordon Sr. and Beatrice; two brothers, Robert Jr. and Joseph; a sister, Carmen Sanford; and nine grandchildren.

By Dennis McLellan

(Los Angeles Times)

(MCT Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)