|

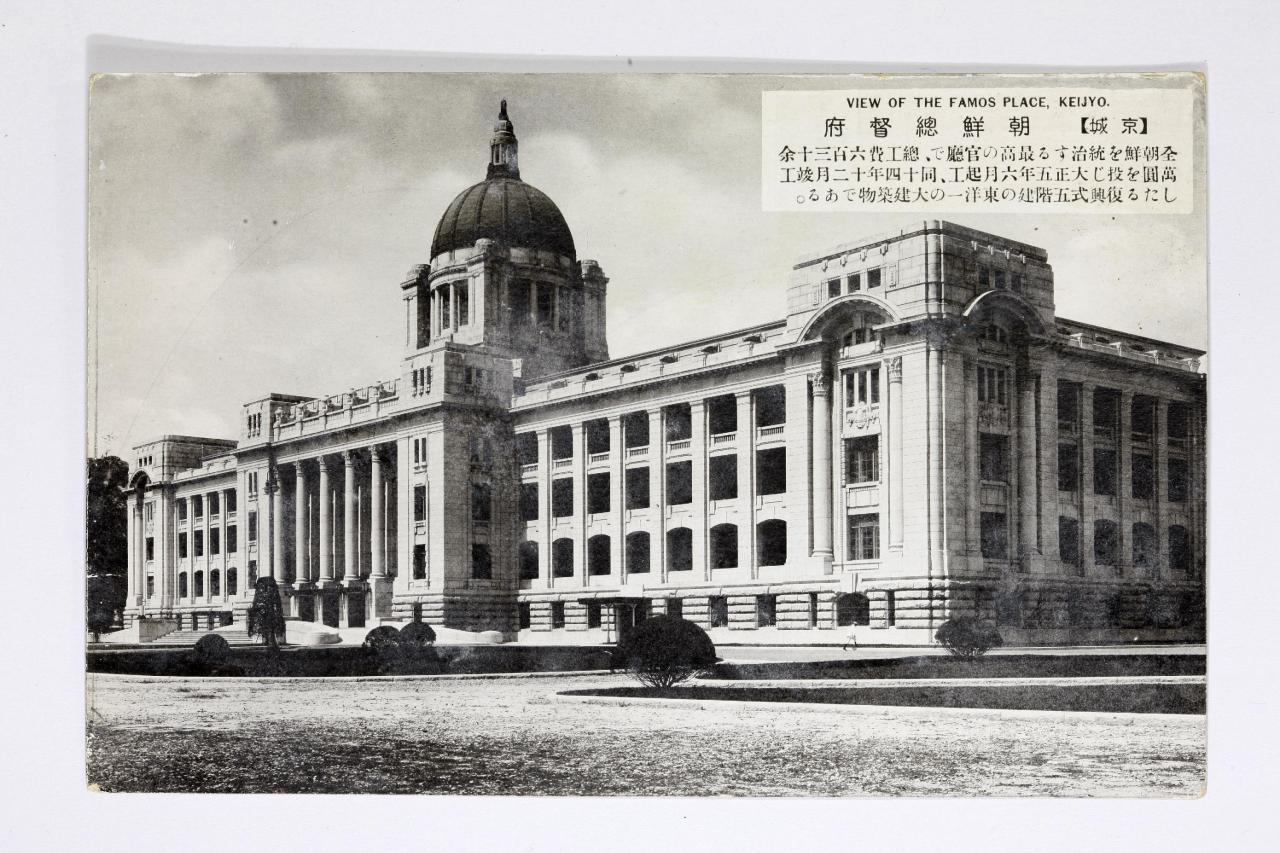

Archival photo of the former Japanese General Government building located in front of Gyeongbokgung Palace in central Seoul (Busan Museum) |

Walking around Seoul, one can easily spot buildings built during the Japanese colonial era.

Park Ga-hee, 31-year-old resident of a neighborhood next to Gyeongbokgung Palace in central Seoul, passes by the Bank of Korea Money Museum on her way to and from work. The building, built in 1912, was the headquarters for the Bank of Joseon during the Japanese colonial era.

“I am aware that the building was used to colonize Korea. It is not a pleasant thing to see the building,” Park said. “But at the same time, that is part of our history. I have complicated and ambivalent feelings toward such heritage,” Park said.

Annexed by Japan in 1910, Korea regained independence at the end of World War II, on Aug. 15, 1945. The buildings from that era are now almost 100 years old or older, provoking debates over whether to preserve the heritages or tear them down for redevelopment.

|

The Seoul Hall of Urbanism and Architecture building is located on the site of the annex of the former National Tax Service building, which was demolished in 2015. The Seoul Metropolitan Council building, formerly known as Keijo Public Hall, is seen on the right. (Seoul Metropolitan Government) |

In 1995, the year that marked half a century after liberation, the Korean government began demolishing the Japanese General Government building, built right in front of the Gyeongbokgung Palace in central Seoul.

“There were intense discussions on whether to destroy the building at the time,” said Alfred B. Hwangbo, professor of the School of Architecture at the Seoul National University of Science and Technology. “It was the 1990s, and the nation was deeply divided about how to accept Korea’s modern history.”

Seoul city tore down another building in 2015 -- the annex of the former National Tax Service building near Deoksugung Palace in central Seoul, to mark the 70th anniversary of liberation in August. The annex, situated between the palace and the Seoul Metropolitan Council building, was built by the Japanese in 1937 in an alleged attempt to conceal the palace from view, experts said.

However, other buildings from the Japanese colonial era still remain intact around the country. In Seoul, those buildings include the Seoul Metropolitan Library, the Seoul Metropolitan Council and Culture Station Seoul 284.

'Difficult heritage’

Heritage sites from the colonial era are usually referred to “dark heritage,” or “negative heritage.” Some experts, however, argue those terms are not appropriate because they emphasize the negative sides without reflecting on other stories about the buildings. It is also important to see how they were used after the colonial era.

“Memories of pieces of architecture change over time,” said Song Seok-ki, a professor at the Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Kunsan National University. In the case of the Japanese General Government building, the building was used as the Capital building until the early 1980s and as The National Museum of Korea in the 1980s. The Korean government made use of the building for longer than Imperial Japan did.

|

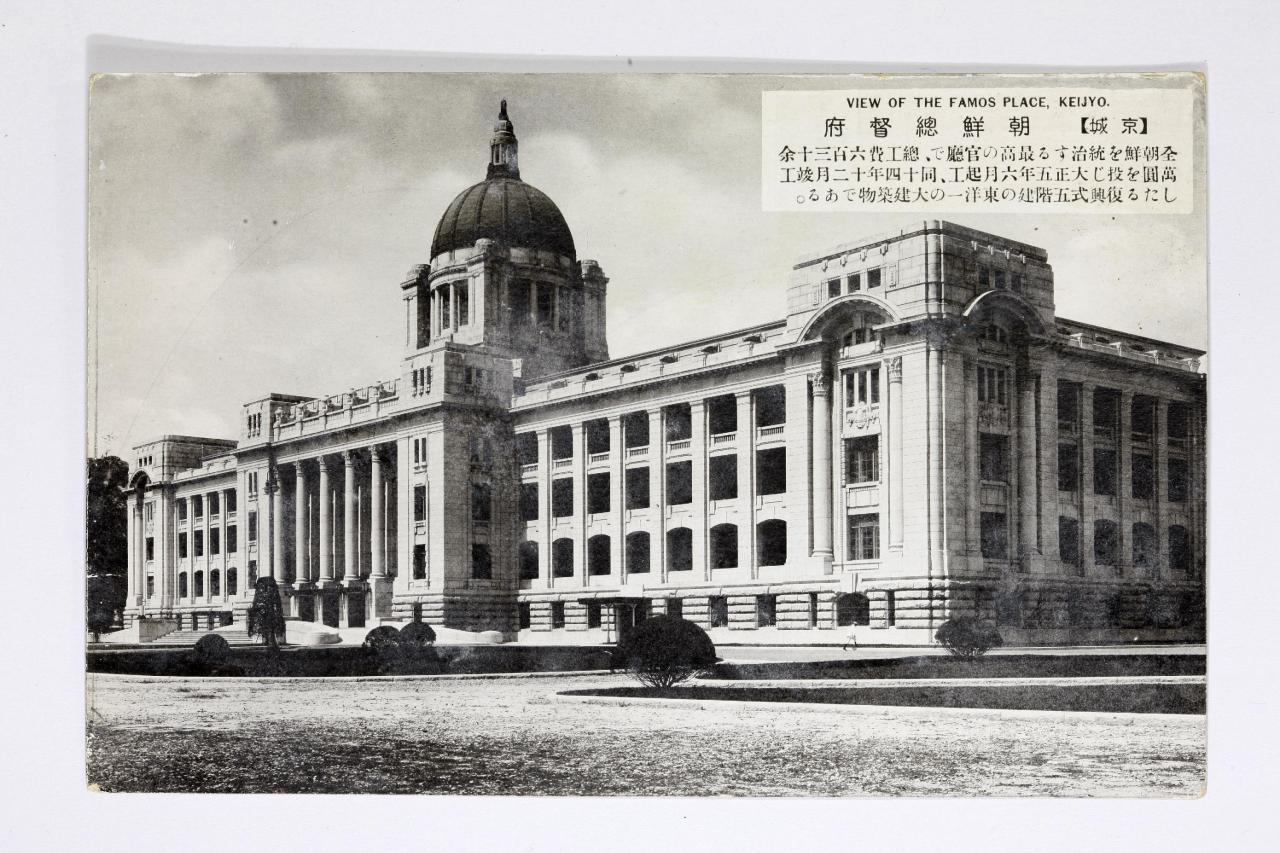

Archival photo of the Seoul Metropolitan Council building, formerly known as Keijo Public Hall or “Buminkwan” (Seoul Museum of History) |

"Memories overlap over time, and we should not define the meaning of architecture, simply pulling out a certain memory, which can be read as a political action. The issue is not as simple as it may seem,” he said.

Lee Hyun-kyung, a researcher at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities, University of Cambridge, suggests the term “difficult heritage” rather than “negative or dark heritage,” warning that the memories towards structures should not be confined to the exploitive usages.

“I don’t think our memories of the Japanese colonial era will change for many years. But we need to understand the accumulated histories about the building although a certain memory can be dominant,” Lee said.

For instance, what is now used as the Seoul Metropolitan Council building in central Seoul, was once a cultural complex in the Japanese colonial era where Imperial Japan propaganda was staged. The building, which was formerly called Keijo Public Hall, was known as ‘Buminkwan’ in Korean.

“Buminkwan was where the last independence protest took place in July 1945, which is a meaningful moment in history to us. That is why we cannot simply call it a negative heritage,” Lee said.

Experts, however, point out a growing trend among young people of visiting regions where Japanese-style houses are clustered, such as Gunsan in North Jeolla Province, to enjoy the exotic atmosphere. Gunsan was used as gateway for shipping rice from Korea to Japan during the colonial era, and many Japanese people settled in Gunsan.

“We should also be cautious about commercially appropriating heart-breaking history,” Song said. “Younger people visit the city and take photos in front of Japanese-style houses without knowledge about the city’s history. It seems that some education on the background of Japan’s exploitation of the city needs to be reinforced at the government level.”

By Park Yuna (

yunapark@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Health and care] Getting cancer young: Why cancer isn’t just an older person’s battle](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050043_0.jpg)