Skepticism is growing over the South Korean military’s ongoing efforts to counter North Korea’s escalated nuclear threat amid increasing calls for a major revamp of its ineffective deterrence strategies and weapons systems.

After the North’s third atomic test on Tuesday, Seoul’s Defense Ministry vowed to accelerate the processes of building the “Kill Chain,” a preemptive strike system, and deploying strategic ballistic missiles, which can cover the whole area of North Korea.

On Thursday, it also unveiled strategic ship-to-ground, submarine-to-ground cruise missiles, underscoring they were capable of surgically striking “specific windows of the North Korean leadership’s offices.”

But these may not be effective enough to cope with the North’s asymmetrical military strategies and assets that include nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, analysts pointed out.

“North Korea now exploits asymmetric and non-linear forms of warfare. It has adapted to the U.S.-ROK (Republic of Korea) military superiority by finding strategies and exploiting the capabilities of asymmetric negation,” said Michael Raska, research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.

“Therefore, South Korea’s new defense strategy must now allow greater flexibility and adaptability to shifts in strategic environment with military forces having the flexibility and robustness to operate in divergent scenarios.”

To this end, Raska stressed Seoul should pursue military innovation and break away from its long-standing, “static, defensive posture” emphasizing conflict and war avoidance, path dependence and over-reliance on the U.S. forces.

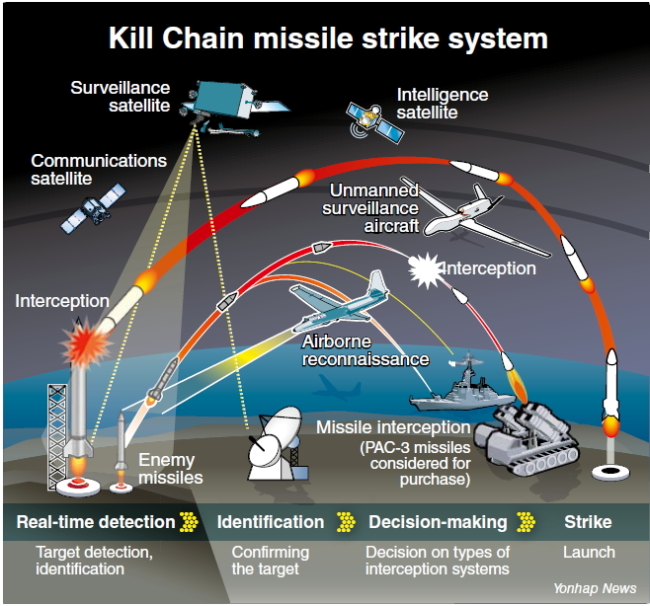

The “Kill Chain” system is at the center of Seoul’s preemptive strike theory. Mobilizing all intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance assets of the South Korea-U.S. combined forces, the system aims to launch strikes within some 30 minutes after signs of Pyongyang’s imminent nuclear or missile provocations are detected.

Seoul initially planned to construct the system by 2015 to target the North’s key missile bases and nuclear facilities including those in its main Yongbyon complex. It consists of four implementation stages ― detection, assessment, decision and strike.

“Using mobile launchers, the North may launch a strike and move away within some 20 minutes. It is very difficult to detect and hit each one of them in a short period of time,” said a military expert, who declined to be named, citing his organization’s policy.

“It would have some psychological impact to threaten the North. But frankly speaking, it is like the North with nukes has live ammunitions while we are bluffing them with blank ammos.”

The North is known to have some 100 mobile launchers that can carry mid-range ballistic missiles that put the whole of South Korea within striking range. The launchers are mounted on large military vehicles with six to eight wheels. Analysts believe the vehicles have been smuggled from China or modified based on Chinese models.

The North reportedly has up to 40 mobile launchers that can carry Scud missiles with ranges of between 300 and 1,000 km, up to 40 launchers for Rodong missiles with a range of 1,300 km, and 14 launchers for Musudan missiles with ranges of between 3,000 km and 4,000 km.

Aside from the constraints caused by the mobile launchers, some experts expressed concern that under the Kill Chain system, the South would have to rely inordinately on U.S. intelligence assets. Seoul retakes wartime operational control from Washington in December 2015.

Seoul plans to deploy a military reconnaissance satellite by 2021, while uncertainty still remains high over the fate of Seoul’s high-profile project to acquire the high-altitude Global Hawk spy drones made by Northrop Grumman based in Virginia.

Seoul has sought to buy four of the long-endurance drones by 2015 with an initial budget of 450 billion won ($414 million), but the project has been stalled due primarily to their increased prices.

“(Given the OPCON transfer), the problem facing the South Korean military is that it should excessively depend on the U.S. for intelligence as it does not have a military intelligence satellite and any high-altitude spy drones,” said Kim Yeoul-soo, politics professor at Sungshin Women’s University.

“The South has to build a complete system that can monitor all of North Korea around the clock with a military geostationary orbit satellite and spy drones so that it can lessen our reliance on the U.S.”

Amid the increasing nuclear threat, calls have mounted that Seoul should start considering whether to develop its own nuclear deterrence or ask the U.S. to redeploy its tactical nuclear weapons.

But experts largely concur that “nuclear balancing” is unrealistic given that the U.S., the South’s central security ally, has been leading the global initiative of arms control under its much-trumpeted vision of a “nuclear-free world.”

“Should the North become a de facto nuclear state, there might be no other option for Seoul but to develop its own nuclear arms to deter the North. Obama’s nuclear-free world vision is, frankly, only idealistic. We never know what kind of a nuclear policy the next U.S. government might adopt,” said the anonymous security expert.

“Seoul can claim to the U.S. that it needs to have nukes as a political, defense means, not for any actual military use. The South is not a rogue state, would not threaten others, but just for self-defense. With nuclear arms, the North would regard the South as a legitimate negotiating partner of the same military might.”

Some experts noted that Seoul has focused mainly on the hardware of its military rather than the software, underscoring it should alter its military concepts, tactics and strategies in line with the changing security landscape.

“South Korea has focused primarily on the ‘hardware’ side ― allocating resource for the procurement and acquisition of selected advanced weapons technologies, systems and platforms whether imported or indigenously developed platforms, which were then integrated into existing organizational force structures and operational concepts,” said Raska of Nanyang Technological University.

“However, the required ‘software’ components ― the relevant organizational, conceptual and doctrinal innovation to utilize the new technologies ― have not been implemented.”

The military expert also pointed to the protracted over-reliance on the U.S. forces coupled with existing inter-service rivalries and their varying doctrinal and technological preferences as major hurdles facing the South Korean military.

“One could argue that South Korea’s traditional security paradigm precluded greater flexibility and adaptability in translating selected defense reforms into practice, and essentially led to incremental military innovation,” he said.

“The principal challenge for South Korea’s military is developing a ‘dynamic’ range of capabilities that are agile, flexible, affordable and multi-mission oriented for a broader range of potential contingencies.”

To deal with the incremental military challenges from the North, experts also stressed Seoul should bolster its security cooperation with the U.S. and Japan.

Some also argue when the North Korean threat further increases with additional nuclear tests, Seoul might have to consider asking the U.S. to delay the transfer of wartime operational control.

Kim Jang-soo, the designate for the incoming government’s top security official, has said that the OPCON transfer would proceed as planned unless there are “serious security problems” caused by armed clashes between the two Koreas or South Korea’s lack of preparation for the transfer.

During a summit meeting in 2010, President Lee Myung-bak and his U.S. counterpart Barack Obama agreed to delay the transfer to December 2015 from April 2012 in the wake of the North’s sinking of a South Korean corvette.

By Song Sang-ho (

sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)