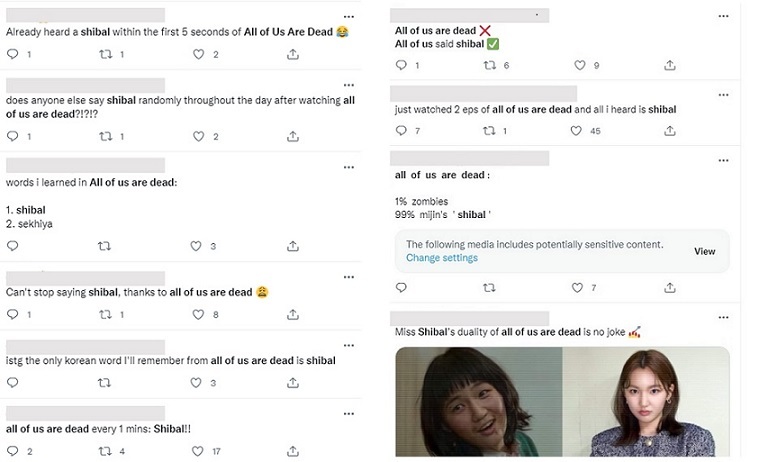

One tweet uploaded on Jan. 31 reads, “Just watched 2 episodes of ‘All of Us Are Dead’ and all I heard was ‘ssibal.’” A Feb. 1 tweet from a different person says, “the show is basically 20 percent zombies and 80 percent ‘ssibal.’”

In the first three episodes in which a mysterious disease begins to spread and turn infected people into zombie-like creatures, more than 120 curse words can be heard.

Along with “ssibal,” which is a vulgar word used when something goes wrong or to insult somebody, various curses and slang terms are exchanged between teen characters of the drama, such as “byeong-shin,” “gae saekki,” “jiral,” “jonna” and “nyeon.” These words can be translated into words like moron, bastard, bullshit and bitch, depending on the situation.

Exaggeration or reality?

The show’s use, or overuse, of slang words has even native Korean speakers divided.

While some say there are exaggerations, others think the drama portrays the language of Korean teens quite accurately.

“There was a scene in episode three, where students shouted at each other and exchanged curse words even though their homeroom teacher was right in front of them. It’s true that teenagers these days use a lot of slang words, but they tend to watch their language in front of teachers or parents,” said Park Sang-wok, a second year student at Anyang Arts High School.

Another high schooler Yoo jin-seok said he didn’t notice anything strange. Curse words are already part of school life, according to the 18-year-old living in Suwon.

“Me and my buddies use ‘ssibal’ almost every half hour whenever talking about each other’s problems or even when discussing good news.”

He said the curse word, depending on the tone the speaker is using, could also be used as a positive reaction to something.

“Of course it’s inappropriate to use swear words at school, but some, especially ‘ssibal,’ have become a common expression of happiness, sadness or surprise among teens,” he claimed.

Yoo also said words like “byeong-shin” or “saekki” are often used between close friends just casually.

A 2020 survey backs Yoo’s claim.

Of the 3,429 young students aged between 9-18 across the nation, surveyed by the National Institute of Korean Language in 2020, nearly 67 percent said they used curse words in their everyday conversation with friends. While 36.1 percent said using curse words is not the right thing to do, another 28 percent said it’s OK to use them in certain situations.

Cultural experts raise the need for local content creators to keep a balance between realistic depictions of society and a proper use of language.

“If characters from TV shows and films only use polite language, viewers would feel a great distance between the shows and their reality. A realistic representation of the times is important, which is what many people expect from the film and entertainment industry,” said culture critic Jeong Deok-hyun.

“However, producers should refrain from overusing slang words, as it can negatively affect the language habits of young students, who are more heavily exposed to the media than ever before with the rapid rise of social networking platforms.”

An expose on Korean school life?

Another aspect of the zombie-apocalypse series that has viewers hooked is its portrayal of Korean school life and interactions between students.

Chris, a 29-year-old Dutch man, said he was captivated by the scene where On-jo, one of the lead female characters, gave her name tag to her crush Soo-hyeok as a confession of love.

“I grew up in a country where school uniforms are not mandatory. Asking someone out by giving a name tag was incredibly cute and clever,” said the YouTuber, who has uploaded reaction videos to all of the episodes on his channel Boke React.

Whether or not Korean teenagers actually share their name tags as a romantic gesture has been a hot debate topic in online spaces.

In a behind-the-scenes commentary, the actress who played On-jo, 18-year-old Park Ji-hoo, said that exchanging name tags is “not a common way of confessing love among Korean high school students.”

Some argued it was one of the popular methods of confessing love back in the 2000s, when the original webtoon was released.

“Students had spare name tags just in case they lost them. I remember many couples had each other’s extra badge on the right side of their blazer. Some uploaded pictures of the them on Cyworld,” recalled Jin Jong-hwan, a 29-year-old female office worker in Seoul. Cyworld was Korea’s most popular microblogging platform before the era of Facebook and Twitter.

Another foreign viewer living in the United Arab Emirates found it interesting that students in the drama are the ones who keep their classroom clean.

“It was very interesting that the characters take responsibility for their school’s cleanliness. Students in my country do not clean their classrooms. I think it’s such a great idea that students are the ones who clean their classroom,” said Roza, aged 23.

“Another thing I found super interesting is that the characters take their shoes off in school and use slippers instead.”

Lani, a 25-year-old college student in Berlin, expressed shock at the portrayal of hatred against classmates living in poverty.

In the third episode of the show, Na-yeon calls her classmate Kyung-soo, who lives in a public housing unit provided by the government for low-income families, “gisaengsu.” It is the shortened form of a word referring to a basic livelihood support recipient. Its pronunciation is similar to the Korean word for “parasite” (gisaengchung), and is thus used to denigrate welfare recipients.

“After watching the show, I read some news articles about how some Koreans, especially those living in affluent neighborhoods, discriminate against residents of public housing complexes. I saw a picture of public apartments painted in different colors from private ones. I was surprised that Korean teenagers made new words to snub the poor, but on the other hand, Na-yeon’s hate speech represents a problem of economic segregation, which is universal across the globe,” the viewer said.

By Choi Jae-hee (

cjh@heraldcorp.com)

![[AtoZ of Korean mind] Ever noticed some Koreans talk to themselves?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/03/20241103050186_0.jpg)

![[Breaking] North Korea fires short-range ballistic missiles: JCS](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/05/20241105050038_0.jpg)