|

Health care workers transport a COVID-19 patient outside an isolation ward in a public hospital in Seoul. (Yonhap) |

Omicron is by far the most heavily mutated variant of COVID-19 to date, and on course to dethrone delta as the dominant strain.

Since the strain was first detected in Korea on Dec. 1, the variant has been found in over 160 cases here. Of them, 39 have recent travel history and the rest are close or indirect contacts. Community transmission, public health authorities say, is probably already underway.

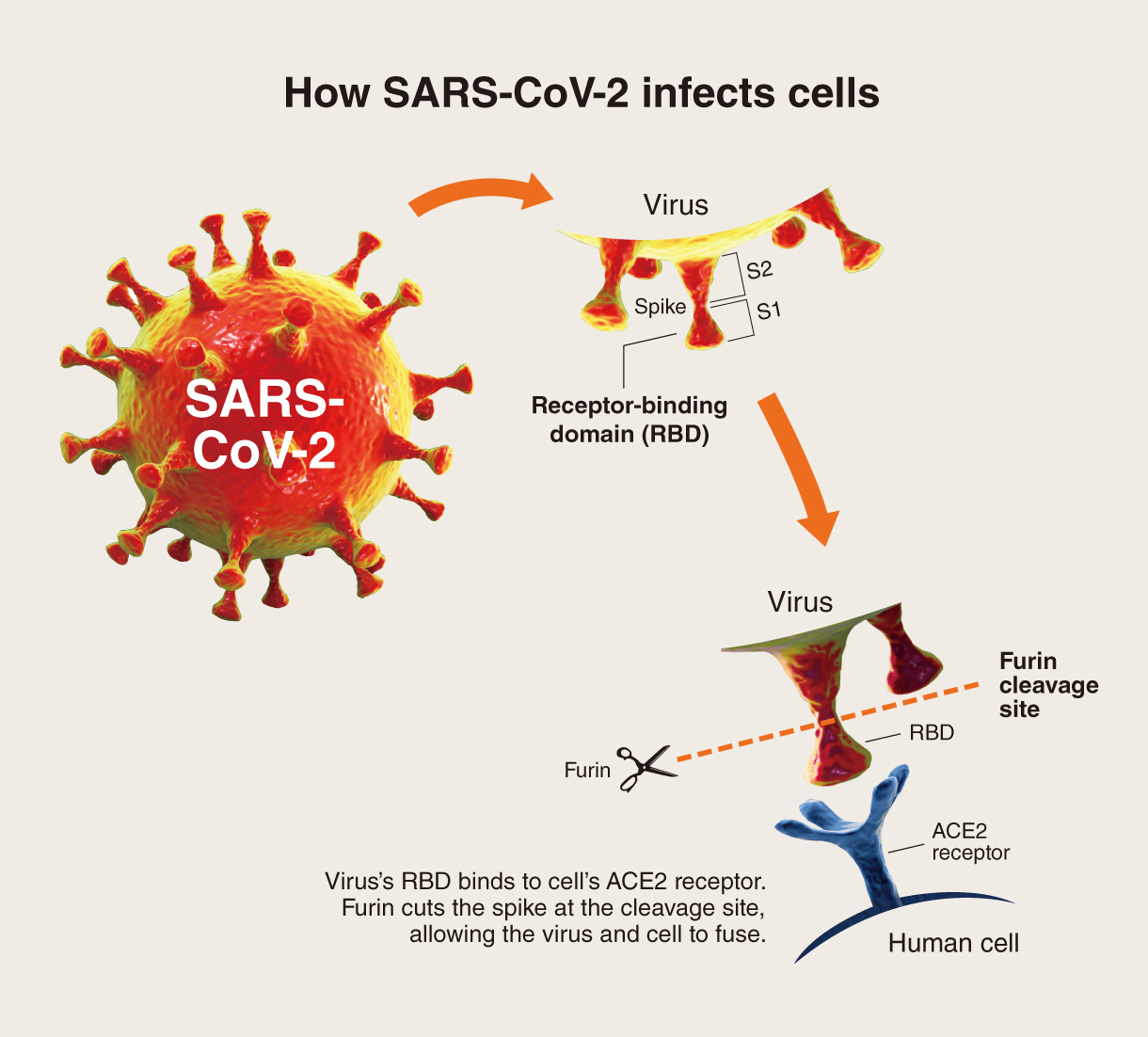

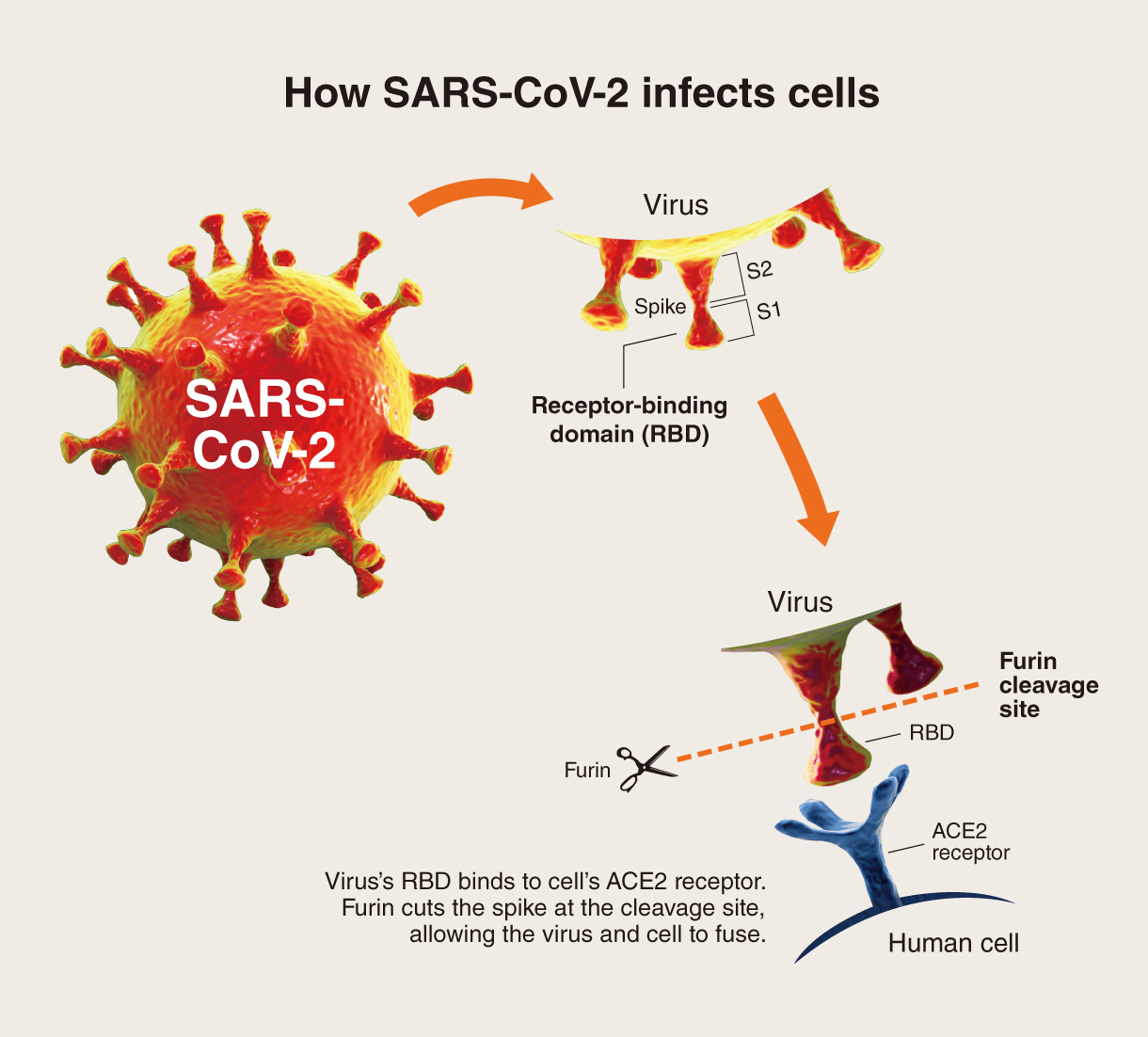

To understand the implications of the newest variant, too nascent to be able to grasp the full extent of its abilities, it’s important to first understand the role the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19, plays during an infection.

|

How the coronavirus infects cells |

The spike proteins comprises two subunits, S1 and S2. The outermost point of the spike, S1, includes the receptor-binding domain, or RBD, that binds to the human cell’s ACE2 receptors. After it is bound, S2 is responsible for mediating the fusion of the virus with the cell.

Omicron possesses multiple mutations in the RBD part of S1 that appears to give the virus higher affinity for ACE2. It also has mutations near the furin cleavage site of S2, which is where an enzyme called furin snips the spike and triggers virus-cell fusion. Mutations around this site could allow the cleavage to occur more efficiently and as a result boost the virus’ transmissibility.

What omicron’s mutations can tell us

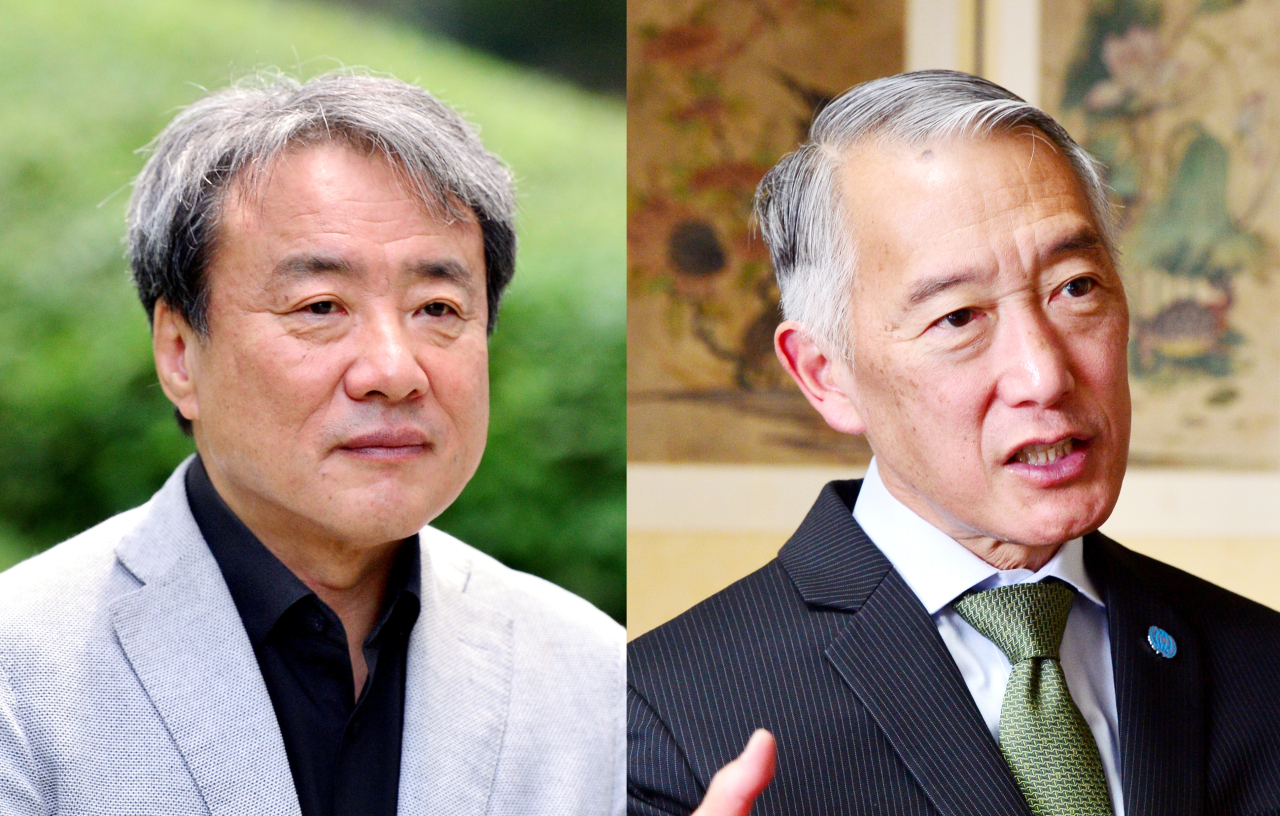

Dr. Paik Soon-young, an emeritus professor of microbiology at Catholic University of Korea, says omicron has features that may make it more transmissible and immune-evasive. But on the bright side, the newest variant of concern looks like it will be less severe, he said.

Not every mutation seen in omicron is relevant nor worrisome, he said. But omicron’s emergence has sparked concerns due to the sheer number of changes in its spike protein -- a whopping 36, according to early samples. The locations of the mutations in the spikes can provide some clues as to how much risk it may pose, he said.

About two-thirds of the over 30 spike-protein mutations found in omicron are shared with other major variants that have turned out to be more infectious and evasive of vaccines and monoclonal antibodies, he said.

In South Africa, where the new variant was first detected, cases have multiplied rapidly, outpacing earlier variants. Outside of South Africa, it has already replaced delta in London and is on course to becoming dominant in the rest of Europe and in the US by sometime in January, according to projections by health agencies there.

Aside from its highly altered spikes, omicron also has mutations in the nonstructural proteins that are responsible for viral replication. These mutations appear to have damaged the nonstructural proteins from functioning properly, and thereby may work to attenuate the virus’ ability to cause severe disease.

Early reports from South Africa have linked omicron with mild disease, he said. One study said the risk of hospital admissions among adults was 29 percent lower with omicron than the original virus -- while noting, that may have been influenced by the fact that the majority of the South African population has already been previously exposed to COVID-19.

Korea’s data is still scant, but none of the patients with confirmed or suspected omicron infection fell sick enough to be hospitalized, experiencing only minimal to mild symptoms to date, according to the official data.

Still, Paik said the same rules -- personal hygiene, crowd avoidance and mask wearing -- remained vital to guard against omicron. Even if the virus may be less virulent in itself, if a large number of people become infected, then that would translate to a corresponding increase in hospitalizations and deaths.

He added that it was not easy to predict how the variant might behave using only its mutation profile. Other alarming variants that came before, like delta plus, have failed to spread as far as initially feared. There was a complex interplay of variables such as vaccination rates and our collective behaviors that could impact the course of a virus.

So how did omicron end up with over 50 mutations?

Omicron has accumulated a lot of mutations of the past variants, he said. This could be explained by what is known as recombination, where two strains swap fragments of genetic material during a co-infection event -- although it is also possible that it could have developed these mutations independently.

The current variant landscape in Korea is mostly delta and very few omicron. He said that for instance, over the process of competing for dominance, the two variants could, in theory, merge and spawn another recombinant variant.

“Variants are not all bad news,” he said. “The virus’ instinct isn’t to kill, but to hang around us as long as it can. So if omicron is indeed less severe, and it goes on to overtake delta, then it may improve our odds against the pandemic. Then again, it’s too early to tell.”

Some relief was expected as new antiviral pills were coming, which are projected to be “a better match for not just omicron but variants in general than monoclonal antibodies,” he said.

Monoclonal antibodies, which are developed to prevent viral entry by targeting specific receptors, might not recognize the mutated bits of the virus’ spike protein. Pills, on the other hand, are designed to inhibit replication of the virus after infection is already underway.

Even if it’s mild, it’s come at a bad time

Dr. Jerome Kim, the director general of the International Vaccine Institute, said, “While maybe less severe or mitigated by vaccination, the fact that omicron is so much more transmissible means that the absolute number of hospitalizations could rise.”

Korea’s hospitals and ICUs are already suffering from the ongoing outbreak. “If it even adds 10 percent on top of the current ‘delta-related’ pressure on health care -- where would we be?”

Kim said some lessons to take away from the latest surge was a reminder that vaccine-induced antibody protection against disease decreases with time. “The elderly should probably have been boosted earlier and messaging about risk should have accompanied the loosening of restrictions more intensively,” he said.

“Omicron, with its mutations and the loss of protection seen over time, is one variant we need to be worried about and get boosted for,” he said.

The mutations in the spike protein, where many of the vaccine-induced protective responses are directed, make omicron “a more difficult target not only for vaccines, but also for several of the therapeutic monoclonal antibodies,” he said. Compared to delta, with omicron, there may be 30 to 40 times reduction in the level of protection as measured by neutralizing antibody.

“Even with the two-dose mRNA vaccine primary series, early data from test tube studies from several different groups suggests that unless the levels of protective antibody can be increased -- i.e. boosting --, many, if not most of the tested samples could lose the ability to ‘neutralize’ COVID-19.”

Though omicron may weaken our vaccine-derived neutralizing antibodies, another component of the immune systems known as T cells might still recognize the new variant and limit progression to severe COVID-19.

An article that Kim co-authored, published Sept. 8 in Nature, said that compared with neutralizing antibodies, COVID-19-specific memory T cells are “maintained for a relatively long time.”

“There is increasing evidence that variants of concern rarely escape memory T cell responses elicited by infection or vaccination,” it read.

In bracing for an omicron spread, he said public health authorities should monitor ICU and isolation ward capacities and prepare for potential curtailment of medical services to essential only. Enhanced restrictions on gathering, reinforcement of distancing and workplace safety were among tactics to be considered.

There should also be an expedited review of the monoclonal antibody treatment being used here and its ability to neutralize omicron, while purchasing and evaluating emergency approvals of antivirals and antibody therapies.

“I presume the government is already doing all this,” he added.

As for prospects of updated vaccines coming along, he said that at this point, there wasn’t much information available on whether the new vaccines would be able to generate higher levels of protection than the mRNA vaccines.

“Data from newer vaccines that have completed testing and are awaiting WHO approval -- Novavax, Clover, Zhifei -- or are still in testing -- Sanofi, SK bioscience, etc. -- are still pending,” he said. But if we should need one, most companies should be able to develop, test and get approval on variant vaccines “in less than half the time it took originally.”

He added that omicron gave more reason to encourage parents to vaccinate their children now, citing reports out of South Africa that it might be more severe in children.

“While omicron isn’t big here yet, it will be. And when it comes, if we aren’t prepared to get boosted and vaccinate our school-age children, we will be putting more ourselves and others at risk,” he said.

“We cannot predict when the next delta, or the next omicron will come. Until we have better vaccines that last longer, offer broader protection against diverse variants, or block transmission more effectively, we will need to be on guard.”

|

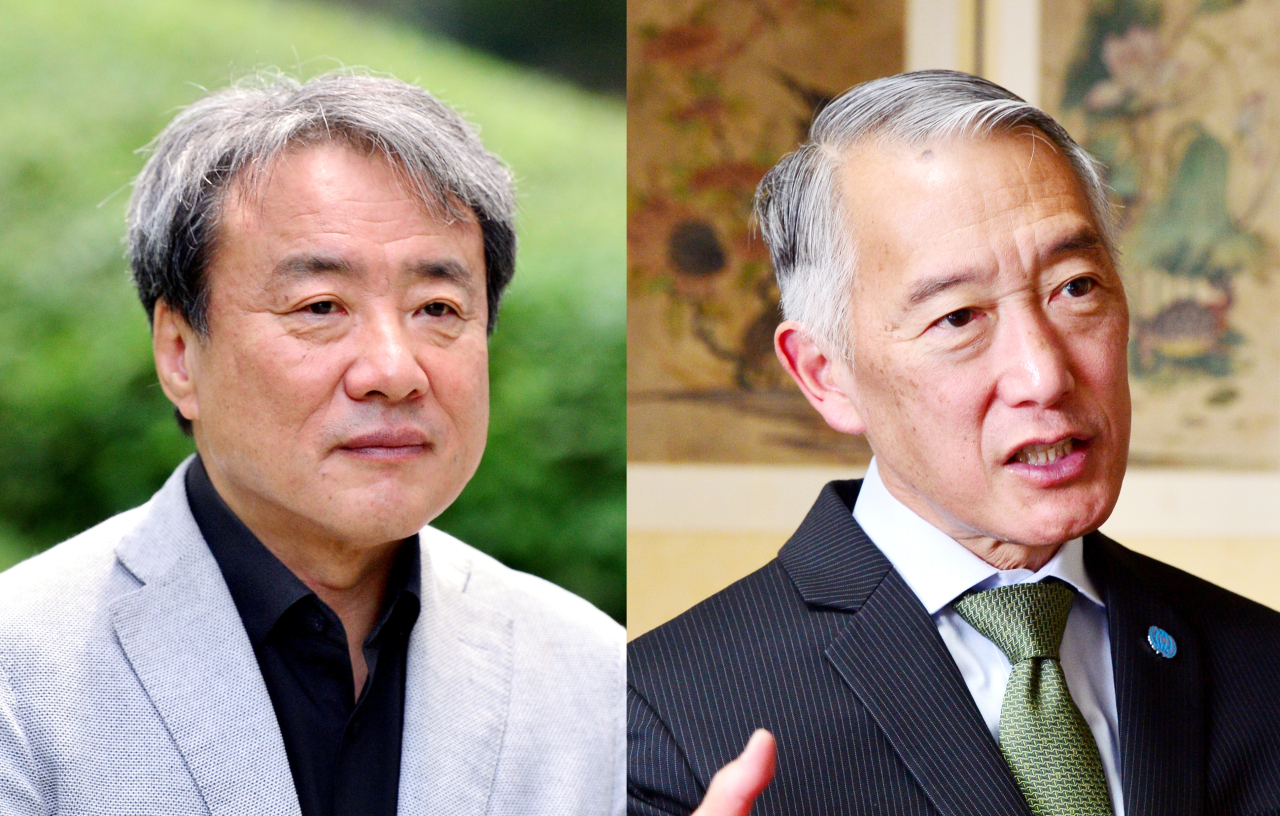

Dr. Paik Soon-young, an emeritus professor of microbiology at Catholic University of Korea (left); Dr. Jerome Kim, the director general of International Vaccine Institute (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |