Experts agree on need to raise charges to the level of cost, call for linking to fuel prices

Korea Electric Power Corp. asked the government on April 26 to raise electricity rates by an average of 13.1 percent. The firm increased charges twice last year, in August and December.

The root cause of repeated requests to hike electricity rates is that KEPCO sells electricity below cost. Inflation fears have led the government to apply tight price controls on rates, even as rising international oil prices increase the cost of production.

|

An employee works at Korea Power Exchange in Samseong, Seoul, with electricity usage rising amid continued hot weather. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) |

Experts share the view that electricity prices should be raised to cost levels to enable KEPCO to end its chronic run of deficits. The state monopoly recorded 3.5 trillion won ($3 billion) in net losses in 2011 alone.

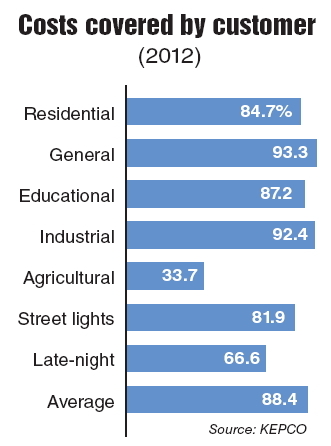

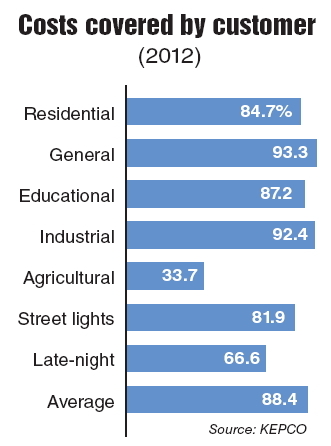

Its cost recovery is estimated at 88.4 percent for 2012. This means that for every 100 won of electricity KEPCO sells, it loses 11.6 won. Experts believe that the continued below-cost prices stimulated a surge in inefficient use of electricity. In other words, people were using cheap electricity like water. Excessive electricity consumption was one of the factors blamed for nationwide brownouts on Sept. 15.

Cheap prices, excessive consumption

According to one KEPCO official, higher electricity charges are inevitable, and will curb demand if they are introduced before usage peaks in the summer.

An official of the Ministry of Knowledge Economy agrees, saying: “It is important to reduce demand for electricity this summer, considering difficulties in matching surging demand with supply change. Charging more is one effective tool to do that.”

Korea consumes more electricity than other countries. Its electricity use against gross domestic product was 1.7 times larger than the average for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in 2009. Japan used 61 percent of the OECD average and the U.S. used 107 percent.

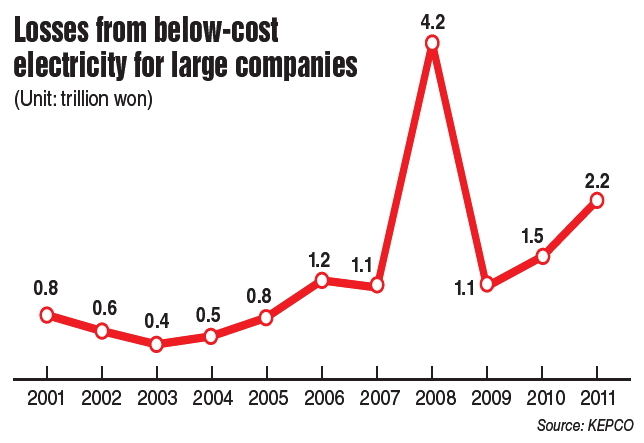

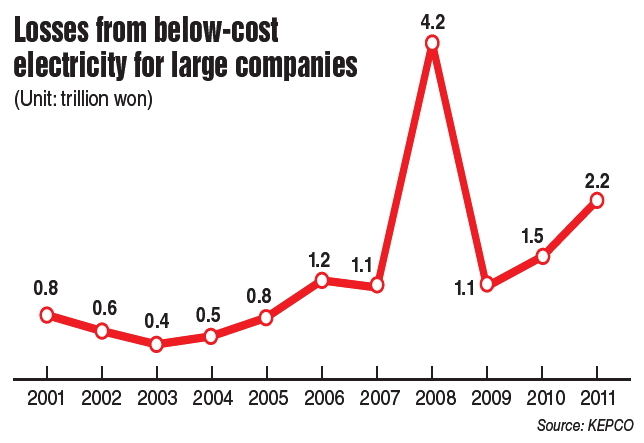

According to the International Energy Agency, if electricity use by the manufacturing sector is measured against GDP, the U.S. marked 51 percent, Japan 31 percent and Germany 37 percent of Korea’s rates in 2011. Based on this, it would seem there is room to reduce electricity waste and demand by raising rates for industry, which accounts for 55 percent of the nation’s demand. According to KEPCO, which has followed the government’s policy to foster the manufacturing industry for economic growth, it lost a total of 14.4 trillion won from 2001 to 2011 from below-cost sales of electricity for industrial use.

“Cheap electricity attracted energy-intensive facilities, such as carbon fiber factories and information technology data centers, from abroad,” said Yang Yi-won-young of the Korean Federation for Environmental Movement.

“The lowest rates system for light load hours or times of low electricity usage, currently applied to industrial and commercial users, instigated electricity consumption. Some high-rise office buildings show off glittering glass faades, but disregard concern about energy efficiency. Large discount stores were open overnight, for example,” she said.

Need to raise rates fairly

The government has not decided yet on the proposal for a raise in electricity charges, considering inflation and other economic factors, but it seems unavoidable to raise them, given the accumulating deficit of the state enterprise.

“It is inevitable to raise electricity charges for most users as international petroleum and gas prices have risen,” Minister of Strategy and Finance Bahk Jae-wan said during his visit to a foreign-invested firm in Cheonan, South Chungcheong Province, on May 23.

“Prices are relatively stable and the Ministry of Strategy and Finance is well aware of the necessity of raising charges,” Minister of Knowledge Economy Hong Suk-woo said on May 17.

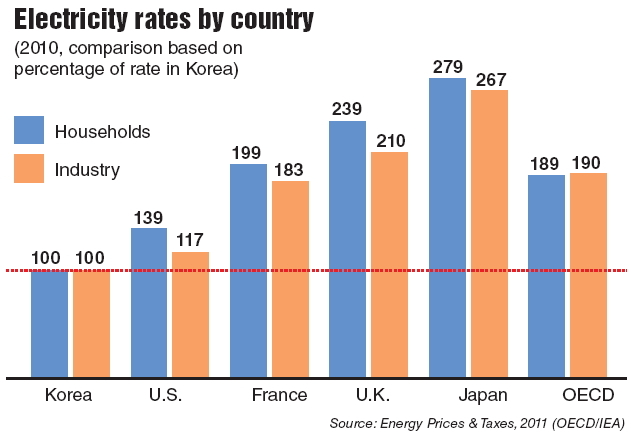

“Currently, our industrial-use electricity charges are the cheapest in the OECD. So far, companies have performed their industrial activities for a comparatively cheap price. I want them to understand that fully,” Hong said.

Korea provided the cheapest electricity in the OECD in 2010. Its charge per kilowatt-hour used in households was $0.083, cheaper than the OECD average of $0.157. Corresponding figures were $0.116 for the U.S. and $0.233 for Japan. In terms of the unit price applied to industrial electricity, Korea marked $0.058, lower than the OECD average with $0.11, the U.S. with $0.068 and Japan with $0.154.

Some local news media report that the government will likely raise industrial and household electricity charges by 6 percent and 3 percent, respectively, this time.

The problem is, then, how to raise rates in a fair way for different users.

Experts argue that the government should raise industrial electricity charges, because industrial use takes up most of the nation’s demand. In 2011, KEPCO lost 1.6 trillion won from industrial power supply, and 500 billion won in sales of agricultural electricity. Of the industrial sector deficit, 76 percent benefited large manufacturers. Of the losses from agricultural electricity charges, 40 percent went to benefit large agriculture companies. Due to the below-cost sales of electricity, KEPCO, continued to support large manufacturers such as Samsung Electronics and Hyundai Motor, which are making profits.

“Price hikes should be approached from the perspective of curbing demand. To do this effectively, it should target those users with low energy efficiency,” Yang of the Korean Federation for Environmental Movement said.

“A progressive scale, currently applied to households, should be extended to commercial users including office buildings and large retail outlets.”

Another expert said that electricity charges should be determined to move in step with the cost of supply.

“Electricity charges need to be raised,” Jhung Han-kyung, senior researcher of the Korea Energy Economics Institute, said.

“The cost of generating power varies according to the demand for electricity. Costs go down as demand lowers, and up when electricity is in high demand. So, it would be reasonable to differentiate rates by demand or usage.”

Backlash from businesses

Business circles oppose the reported scope of rate hikes for industrial electricity.

“It is not right to raise only industrial electricity charges sharply,” Lee Dong-geun, executive vice chairman of the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry, told reporters on May 30.

“Industrial circles regard it appropriate to increase them by 3 percent, which is the inflation rate.”

A sharp increase in electricity charges would add to the problems of small and medium-sized companies already in financial difficulty, so it may weaken the industrial competitiveness of Korea, the KCCI says.

“It is desirable to raise charges gradually in balance with the other categories of users and on the basis of cost recovery percentages. The authorities are urged to keep equity with other users including households when they raise rates,” Lee said.

“Rate adjustments should be transparent and reliable so that businesses will be able to make predictable business plans in the medium and long term.”

Businesses point out that cost recovery of industrial electricity ― an estimated 92.4 percent in 2012 ― is higher than that of households, which is 84.7 percent. In 2011, cost recovery of household electricity was 86.4 percent against 88.7 percent for industrial electricity. After the two rate raises last year, the gap widened.

Civic groups and KEPCO, however, say that businesses have benefited from the below-cost sales of electricity under the policy to promote manufacturing.

Cost basis and competition

Currently, electricity charges are divided into seven categories: residential (households), general (commercial), educational, industrial, agricultural, street lights and late-night use. Except for the late night category, electricity charges are divided up according to the end user. Generally, household supply runs at a low voltage, and industrial electricity at a high voltage. Low-voltage supply is more costly, because it requires long lines of transmission and distribution as well as voltage-reduction appliances.

Experts say that it would be rational to differentiate charges by voltage rather than by end user. Their point is to raise fees depending on voltage and the times of use, which affects demand and power generation costs.

“In the current pricing system, charging by voltage is a long-term issue under review. It is a cost-based, reasonable charge system,” said a KEPCO official, “Electricity is a sort of product, so it is right based on market principles to charge according to how much of it a consumer buys, not who buys it.”

Other alternatives floated by state think tanks such as the Korea Development Institute include the introduction of competition into the industry.

In fact, a package of measures to reform the monopolistic local electric power industry was adopted in 2001. As a result, power generation was separated from power transmission and distribution, and six power generation companies were spun off from KEPCO.

The six are five thermal power companies, and one hydroelectric and nuclear power company. These six companies account for 80 percent of Korea’s power generation facilities, and 90 percent of total power generation.

However, KEPCO still monopolizes retail as well as wholesale channels. Efforts to introduce competition in the field of power transmission and distribution, which means electricity provision, were stalled in 2004.

In the current structure competition or integration cannot be expected to yield positive results, experts note.

Jhung expects consumers to benefit if the government opens the wholesale and retail markets to competition.

“Price competition among electricity wholesalers and retailers will offer end users various rates as seen in the telecommunication market,” he said.

The Korean Electricity Regulatory Commission, which deliberates and decides on electricity charges and other important matters, shares the view that competition in both power generation and distribution will lead to wider consumer choice.

Some experts mention the need to establish an independent regulator of electricity charges. They point out that the current commission under the control of the Ministry of Knowledge Economy is not wholly free from politics. Lawmakers of rival parties call for caution against or oppose increased charges, especially for households. The ruling Saenuri Party stresses the public consensus, while the main opposition Democratic United Party opposes the rate increase for households. The opposition party also criticizes KEPCO of not doing enough to cut costs.

The independent energy regulator of the kind that experts float is an agency like the Fair Trade Commission, which protects consumer interests by fostering fair competition.

There is an opinion that the government should let electricity charges move in step with market forces, not by an artificial mechanism. One of the ideas is to link charges to fuel prices. As international fuel prices go up, electricity charges rise in tandem, curbing consumption automatically. Actually, this system was adopted in July last year, but put on hold due to inflation worries. As a result, KEPCO was banned from reflecting fuel price increases in electricity charges.

In the current trade system, KEPCO purchases electricity from power generation companies for prices including proper margins, but sells it to consumers below cost under the government’s price control. So, the state corporation posted 8 trillion won in the red from 2008, while power-generating subsidiaries chalked up 4.1 trillion won in surpluses.

“Electricity charges are below cost, so if we begin to connect charges to fuel prices after raising electricity charges to the level of cost, we will see a reduction in the backlash from artificial raises,” said a KEPCO official.

As urgent as the need to raise industrial charges is the need to change agricultural charges especially for heavy users. Agricultural electricity charges have been frozen at the cost-recovery level of 34 percent for 12 years. The problem is, however, large farming enterprises benefit from the subsidized electricity originally intended to support small-scale poor farmers. KEPCO has maintained that large farm businesses should pay industrial rates.

By Chun Sung-woo (

swchun@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)