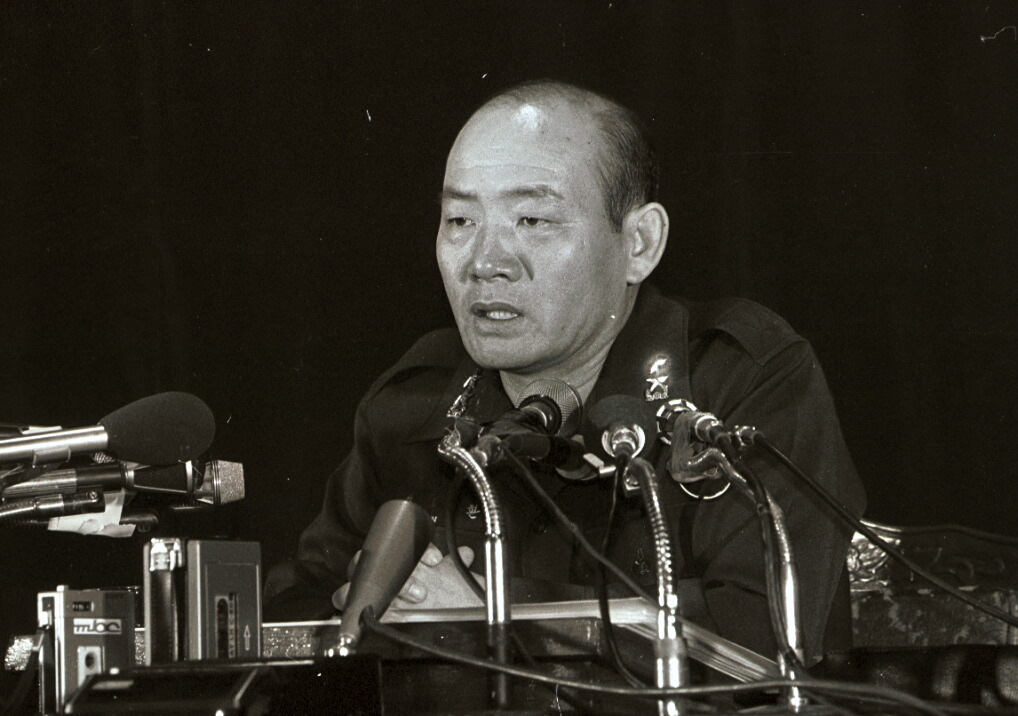

Former President Chun Doo-hwan, one of the most controversial figures in South Korea’s recent history, died Tuesday at the age of 90.

Chun, who died after suffering from multiple myeloma in his later years, leaves behind a bloody and troublesome legacy largely due to a 1979 military coup that led to a bloody crackdown on the 1980 Gwangju Democratic Uprising.

The Army general-turned-politician was born as the fourth son of 10 children in Hapcheon County, South Gyeongsang Province, in 1931, later on joining the military by attending the Korea Military Academy from 1951 to 1955.

He rose through the ranks by befriending powerful figures during his military career. He earned the trust of his predecessor, Park Chung-hee, who made him secretary to the commander of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction after showing support for Park's May 16 coup in 1961.

Chun consolidated his power by forming a secret military club named Hanahoe, composed of his classmates from the Korea Military Academy and other acquaintances. The club laid the foundation for the military coup he led in 1979 following the assassination of Park the same year.

Before serving as president of South Korea from 1980 to 1988, Chun was the nation’s de facto leader in 1979, with Choi Kyu-ha as the figurehead president.

He declared martial law in 1980, citing rumors of North Korean infiltration -- closing down universities, banning political actions and gagging the press. The move caused a nationwide uproar, with people protesting the military presence in their regions.

The opposition was especially fierce in Gwangju, with citizens mobilizing to launch protests and rallies that turned into the Gwangju Democratic Uprising. Under Chun’s direct orders, troops, tanks and choppers were deployed to suppress the protest, massacring activists over the course of two days.

In seeking to cement his dictatorship, Chun dissolved the National Assembly and effectively named himself as president by registering as the only candidate for the presidential electoral college in August 1980. He enacted a new constitution that concentrated power in the president’s hands.

Chun extended his presidential term by controlling the electoral college, continuing his dictatorship until he stepped down in 1988.

As leader of the Democratic Justice Party, he picked Roh Tae-woo as a presidential nominee in 1987. Roh announced the "Declaration of Democracy," accepting the public’s demand for a constitutional amendment to introduce the direct election system.

Despite the changes, Roh won the election and continued Chun’s legacy.

While Chun is mostly remembered as a military dictator who orchestrated bloody crackdowns and perpetrated gross human rights violations, he also brought significant policy reforms and made notable diplomatic achievements, most of which are rarely mentioned due to his dark past.

He abolished a collective punishment system and established a new college entrance admission system that allowed people with few advantages in life to climb up the ladder. He also made initial investments toward the installation of a nationwide telecommunications system.

During his term, South Korea enjoyed high economic growth and low unemployment. The country’s economy grew an average of 12.1 percent between 1986 and 1988, and some have labeled the period as the most prosperous years South Korea has ever seen.

He also introduced a minimum wage system and implemented policies mandating that the rate be negotiated each year while introducing a Reserve Officers' Training Corps recruitment system and designing protective housing policies.

At the same time, Chun abolished the nationwide curfew that was in force for 37 years while eliminating regulations on school uniforms and hairstyles. He lifted regulations on the film industry, opening the gateway for South Korea’s entertainment sector.

Chun also launched professional soccer, baseball and Korean wrestling leagues. He was instrumental in having Seoul host the Summer Olympic Games in 1988.

Yet the Samcheong reeducation camp -- established on his orders in 1980 -- drew immense controversy, as many innocent citizens were subjected to brutal conditions and forced labor. The camp was initially aimed at "cleansing" social ills such as drug trafficking.

The years after Chun’s term were marred by the crimes he committed before and during his presidency.

He and his successor Roh were arrested in 1995 during the Kim Young-sam administration, which defined Chun's military action as a coup. Chun was sentenced to death, but his sentence was later commuted to life in prison. He and Roh were pardoned in December 1997.

Chun faced criticism even later as he effectively ignored a court order to repay more than 220 billion won ($185 million) that the Supreme Court said he had misappropriated. He refused to pay the bulk of his forfeit and lost the privileges given to former presidents due to his convictions for treason and bribery.

He continued to face time in court until just months before his death, appearing in Gwangju courts on libel charges. Chun published a memoir in 2017 defending his authoritarian presidency, and some of the comments contained in the book led to a criminal defamation complaint with the prosecution.

The former leader still faces criticism today, as he never apologized to the victims of the Gwangju massacre.

In his later years Chun saw his health deteriorate rapidly, and he suffered from Alzheimer's disease and blood cancer. Chun is survived by his wife, Lee Soon-ja, three sons and a daughter.

By Ko Jun-tae (

ko.juntae@heraldcorp.com)