|

High-end cars are seen driving by luxury stores on Apgujeong Rodeo Street, Gangnam-gu, Seoul. (Son Ji-hyoung/The Korea Herald) |

Kim Young-woo, a 47-year-old bank employee with two teenage kids, has had trouble sleeping in recent months. Kim’s family lives in a posh neighborhood in Yeoksam-dong, Gangnam-gu, southern Seoul, but may not be able to stay there.

“My jeonse contract expires in December. I have to look for a new apartment since I was told that my landlord is moving back to this apartment,” he said. Under South Korea’s jeonse system, the tenant pays a refundable deposit to rent a home for at least two years.

But over the past two years, the cost of a jeonse deposit for a 109-square-meter apartment in Kim’s neighborhood has surged more than 30 percent to at least 1.3 billion won ($1.1 million).

“The problem is not just about soaring prices, but also the high competition to get jeonse apartments because many want to live here in spite of facing a dramatic price surge. Buying is impossible, because getting a mortgage for an apartment worth 3 billion won is impossible.”

If Kim wants to stay in Gangnam, renting is his only option, given restrictions on lending and the tax burden for an apartment worth over 900 million won. He could afford a decent apartment elsewhere in the city with his jeonse deposit, but his family wants to continue living in Gangnam to maintain their quality of life.

The rationale behind Kim’s wish to stay in the Greater Gangnam area is based on a deep belief that it offers better access to Seoul’s elite schools and private education market, to the spacious parks along the Han River and its streams, and to transportation hubs and hospitals.

Greater Gangnam refers to three districts -- Gangnam-gu, Seocho-gu and Songpa-gu.

“It’s the center of everything. Good things are all here. Parents want their kids to enjoy what this neighborhood has to offer, at all cost,” said a real estate agent covering Yeoksam-dong.

|

Apartment complexes and low-rise residential buildings are seen from the observatory of Lotte World Tower in Songpa-gu, southern Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

Without financial leverage, however, few families can afford to buy or rent an apartment in Greater Gangnam.

They often go all out to scrape up the money and borrow to the hilt to climb the social ladder.

“It is a ‘foot-in-the-door’ situation,” said Kwak Keum-joo, a professor of psychology at Seoul National University. “Residents in a Gangnam neighborhood often have a sense of belonging that makes them feel comfortable and accessible to the upper class of society.”

The door to Gangnam and its vicinity seems to be closing, especially to those looking for jeonse contracts. Post-pandemic liquidity has driven up demand for housing in Greater Gangnam over the past couple of years. Now, tenants are bearing the inevitable financial burden.

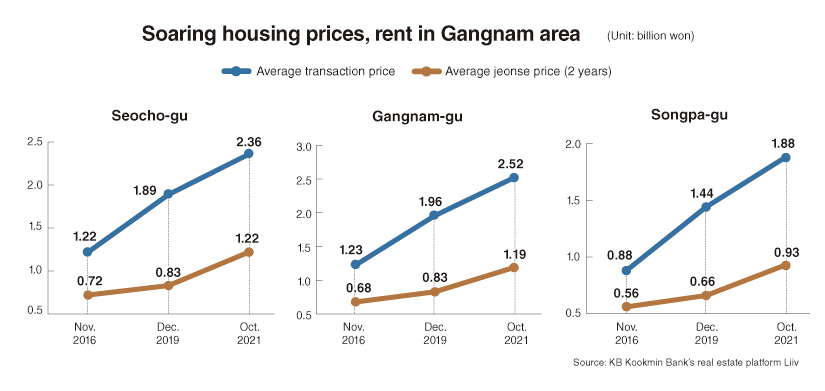

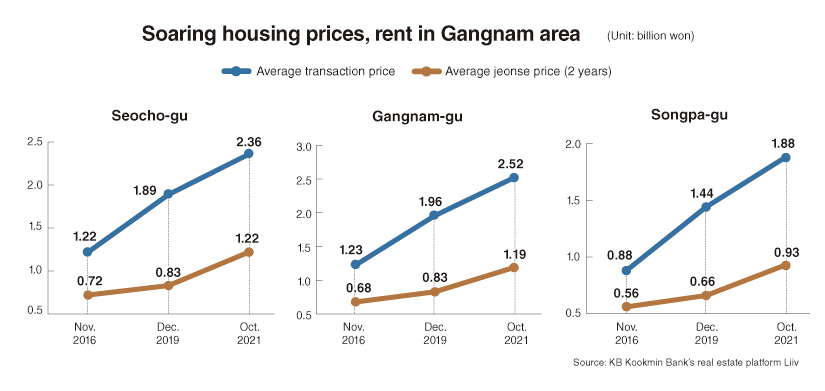

The cost of jeonse deposits in the Greater Gangnam area jumped by an average of 40 to 45 percent from January 2020 to October this year, according to data from KB Real Estate Liiv.

This compares to the 25 to 30 percent average increase in purchase prices for homes in the three coveted districts during the same period.

South Korea’s financial authorities have intensified the jeonse squeeze, along with the housing squeeze in the Greater Gangnam area, by declaring battle against speculative housing transactions there in an effort to limit household debt, which is considered a powder keg for Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

The price of proximity

The double whammy of higher rents and tighter lending criteria affects not only Korean families, but also single-person households in Greater Gangnam.

The area is home to some of Seoul’s busiest business districts, including the tech hub Teheran-ro, where tech ventures can take advantage of ultrahigh-speed optical communication networks. That impressive infrastructure has led to the birth of a number of successful tech ventures in the area, such as e-commerce giant Coupang and mobile travel app Yanolja. Global tech giants such as Apple, Google, Oracle and Qualcomm, to name a few, launched their Korean operations there.

The tech hub has attracted top talent from across Korea.

A 34-year-old single woman surnamed Kim had to relocate from Incheon in February 2020 when she landed a job in Greater Gangnam. Not wanting to commute over 2 1/2 hours a day, she signed a two-year jeonse lease for a place in Songpa-gu in a low-rise residential building, known as a “villa” here, for about 100 million won.

The bargain price was backed by a loan that her workplace sponsored, reducing her debt burden.

Over the course of a year and a half, the price of jeonse in nearby buildings has risen as much as threefold, according to Kim.

Should her landlord decide not to extend the jeonse contract and move into the unit instead, Kim may be headed for financial trouble. In that case, she would be forced to seek out costlier monthly rent elsewhere.

In Korea, jeonse leases are generally preferred because the monthly cost of borrowing money for a deposit tends to be lower than the alternative -- paying monthly rent and a smaller deposit.

Kim also believes another relocation at this point would affect her quality of life.

“I hope to extend my contract,” Kim said. “Rents are skyrocketing, and I cannot find a cheaper space elsewhere. I really enjoy the decent living conditions, various facilities around me and the transportation infrastructure.

“But if I end up being evicted, I’ll have to consider a monthly rental contract, but I think I’ll have to spend a third of my income paying monthly rent if I stay in the Gangnam neighborhood. Monthly rent is my last option.”

During the term of her jeonse contract, Kim changed jobs and got a pay raise. That is not necessarily good news. It poses something of a headache for her.

“A pay raise could affect my loan conditions,” Kim said. “I’m concerned that I might no longer be qualified for the loan because of the pay raise and that I might be unable to borrow as much as I could before.”

Wealth hides in shabby buildings

The high-end districts of Gangnam-gu, Seocho-gu and Songpa-gu have for decades symbolized Koreans’ intense fervor for education, glitzy streets lined with luxury goods stores, a bustling nightlife and the development and convergence of innovative technologies.

It took only a few decades for what was once muddy farmland to turn into the center of everything.

Government offices, prosecutors’ offices, the Supreme Court, prestigious high schools, a bus station and other important sites have been relocated there since the 1970s under an urbanization plan led by ex-President Park Chung-hee. Residents were offered tax breaks at the time, as the government sought to curb the expansion of commercial facilities in northern Seoul bordering on the Han River.

Seoul also built sports venues south of the river to host the 1988 Summer Olympics -- a symbol of national pride and prosperity during the period when Korea experienced its fastest economic growth.

In the meantime, wealth has been concentrated in the Greater Gangnam area, where some 1.6 million people, or 17 percent of Seoul’s population, reside. About 1 in 20 Greater Gangnam residents is officially “rich.”

According to “Korea Wealth Report 2021” by KB Financial Group, some 82,000 high-net-worth individuals -- people with over 1 billion won in financial assets -- dwelled there as of 2020, making up almost half of Seoul’s 178,600 ultra-affluent.

In 2020, some 5,500 people in the three districts gained high-net-worth status, a third of Seoul’s 16,000 entrants.

The purchasing power of the area’s residents shows no signs of weakening. A third of new foreign cars in Seoul -- under 23 brands, including the high-end Bentley, Lamborghini, Maserati, Porsche and Rolls-Royce -- have been registered in Greater Gangnam over the past three years, according to data from the Korea Automobile Importers & Distributors Association.

Five of the 10 department stores with the highest revenues in Korea were located there. Those five locations combined generated more than 20 percent of the 28 trillion won that flowed into all department stores nationwide.

|

A street view of Galleria Department Store in Gangnam-gu, Seoul. (Son Ji-hyoung/The Korea Herald) |

Oddly, some of the richest neighborhoods in Greater Gangnam consist of apartment buildings that are nearly 50 years old.

According to the Land Ministry, a number of residential units in the Apgujeong Hyundai apartment complex and the adjacent Apgujeong Hanyang apartment complex -- both located in northern Gangnam and built between the late 1970s and early 1980s -- sold for around 32 million won per square meter this year.

In one of these buildings, a 245-square-meter apartment in the Apgujeong Hyundai complex built in 1979, fetched 8 billion won. It was the largest deal this year for a single unit in an apartment complex built before 2009.

Reconstruction jackpot

The hype about worn-out apartments stems from expectations that prices will see sudden upshots over the course of reconstruction. A reconstruction project involves tearing buildings down and replacing them with buildings that serve the same purpose.

Korea has a history of refurbishing residential areas across Seoul. Owners of old homes often enjoyed a financial bonanza. The Gangnam area and neighboring districts spearheaded that trend.

A recent example is Gaepo President Xii in southern Gangnam. The apartment complex, built in 1982 with 2,800 households, will have to make way for high-rise luxury apartment buildings with 35 floors -- enough for 3,400 households, including some homeowners within the existing complex.

The reconstruction project, the largest in Gangnam’s wealthy Gaepo-dong, will replace the shabby apartment buildings with upscale apartments by 2024. Residents will have waited more than a decade, since 2012.

On top of all the conveniences that Gangnam neighborhoods have to offer, the apartment complex will feature rooftop pools, indoor climbing facilities, an indoor golf course and cinema rooms.

|

A vacant low-rise apartment building is seen against the backdrop of a reconstruction site of Gaepo Jugong Apts. 4 at Gaepo-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

In adjacent Seocho-gu, large-scale apartments built in 1974 for 3,600 households are set to attract up to 7,400 households through a 2.6 trillion won reconstruction deal. Under the project, 7 out of 10 households will enjoy Han River views.

Reconstruction projects do not necessarily start with the oldest buildings.

To proceed with reconstruction, homeowners or the authorities need to prove that an apartment building is on the verge of crumbling. Once the property is declared unsafe, steps can begin in a process that usually takes more than a decade. But oftentimes, reconstruction plans for worn-out apartments trigger blistering conflicts among homeowners, municipal authorities and builders.

The Eunma apartments in southern Gangnam, built in 1979, are one example. Eunma gained approval in 2001 to establish a “reconstruction association,” an initial step to allow homeowners to set up an advocacy body representing them.

But the decadeslong spat has caused an exhausting delay for over 4,400 households in one of Gangnam’s oldest apartment complexes. Seoul has constantly rejected its reconstruction plans. Homeowners have failed to establish a body so far.

Despite the wrangling, Eunma apartment owners have largely seen their illiquid assets rise sharply in value.

A study carried out by the Korean Center for City and Environment Research at the request of the National Assembly Secretariat showed that Eunma apartment prices surged by 1 billion won on average in the decade leading up to 2020, regardless of their size.

Over the course of that time, homeowners have often sought to relocate as their homes began to grow older. More Eunma apartment owners chose to become landlords instead of living there.

About 3 in 10 owners actually lived in their apartments as of 2020. In 1999, in contrast, 58.8 percent of Eunma unit owners dwelled there.

The research also indicated that the Eunma apartments are seeing more intrafamily transactions -- meaning that aspiring buyers are increasingly losing out to the reconstruction jackpot.

Inheritances and gifts from family members who owned Eunma apartment units accounted for over half of all transactions from January to August of 2020. The proportion barely exceeded 10 percent over the past two decades.

Gangnam children

The “Gangnam real estate never dies” phenomenon also reflects parents’ desire for the ideal environment where their children can study.

As of 2020, Greater Gangnam was home to a third of Seoul’s 14,000 “hagwon,” academies that offer private education and help kids prepare for university entrance exams, data from the Korean Educational Development Institute showed.

Parents in Gangnam were spending 1.2 million won per month on average on tuition, according to a 2019 estimate from the district office.

|

Hagwon advertisements hang outside Eunma Shopping Complex with Eunma Apartments in the background in Daechi-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

What adds fuel to the Gangnam property price upsurge is that excellent students outside the Gangnam districts are not enjoying the same educational opportunities.

The Moon Jae-in administration is moving to abolish special-purpose high schools, established exclusively for elite students across the country, in the belief that they foster elitism.

But the policy, experts say, is likely to lead to fiercer competition among parents to buy or rent homes in either Gangnam-gu or Seocho-gu -- locally known as Seoul School District No. 8 -- so their kids can attend the prestigious private high schools there.

“Special-purpose high schools have so far eased the problems caused by the housing shortage in the Greater Gangnam area,” said Koo Jeong-woo, a sociology professor at Sungkyunkwan University. “If Korea shuts off such elite schools, there are few alternatives left for parents who are keen on children’s education. … The abolition of elite schools has driven up housing prices across the Greater Gangnam area.”

The hefty costs are leaving the younger generation frustrated and anxious about starting families, with the pandemic widening economic polarization, he added, and exacerbating the problems Korea is facing due to its aging population.

“Considering the high cost of living and starting a family, more people would in the long run choose to deviate from the conventional cycle of dating, marriage and childbirth. They might rather be self-satisfactory, by fulfilling their everyday needs with cultural activities.”

Kwak of Seoul National University also suggested that those who grew up outside Gangnam tend to fantasize about life in Gangnam. They often decide to do whatever it takes to parent their kids in the Gangnam area, largely in the belief that kids in Gangnam will form exclusive personal connections that last into adulthood, bringing opportunities to request assistance or exchange favors within a privileged peer group as they grow up.

“The ‘I’m not from Gangnam, so my kids should be from Gangnam’ mindset triggers a phenomenon in which those who can barely afford a family life in Gangnam squeeze into Gangnam and have their kids enjoy the benefits,” Kwak said.

“The fact that they live in the Gangnam area offers them a sense of relief that ‘I’m on the right track, and I’m raising my kids properly.’ Otherwise, they fear moving out of Gangnam because, if that’s the case, they would have nothing left and think what they lived for was nothing.”

By Son Ji-hyoung (

consnow@heraldcorp.com), Jie Ye-eun (

yeeun@heraldcorp.com) and Byun Hye-jin (

hyejin2@heraldcorp.com)

By Korea Herald (

khnews@heraldcorp.com)