|

John Sichi, an American father whose two children were taken to Korea by their non-custodian Korean mother in 2019, walks on a portable treadmill on a street in Seoul, Nov. 29. (Choi Jae-hee / The Korea Herald) |

On a late November afternoon, John Sichi was walking on a treadmill on a street in Seoul. The exercise equipment featured signs on both sides that read “I miss my children so much” in Korean. Next to it stood life-size photos of two toddlers -- a girl and a boy.

It was the American father’s way of expressing his frustration with the South Korean authorities, whose inaction he said is preventing his children from returning to him, their custodial parent.

“I had no more ways to meet my children. She keeps refusing to return my kids, defying the court orders. It's bizarre. You won full custody of a child, but lost everything all of sudden,” he said.

‘Walking, but going nowhere’

Sichi lived in San Francisco with his wife and two children. In November 2019, after a “small fight,” his Korean wife flew to Korea, taking with her the kids who were then just toddlers. She never returned, insisting on raising them on her own in Korea. She didn’t let him stay in touch with them, either.

“My wife basically has full control over the children. They are likely to see a different version of me from the reality,” he said.

Sichi took the matter to court in both the US and Korea. Between 2020 and 2021, he won legal custody of the children and a court order mandating their return to him was issued in both the San Francisco County Superior Court and the Seoul Family Court.

In February, when Korea’s Supreme Court ruled in his favor, finalizing the lower court’s decision and rejecting his wife’s appeal, he thought he would finally be able to reunite with his children.

But that didn’t happen.

Despite the court orders, receiving 5 million won ($3,851) in fines and having to serve 30 days of detention, his wife has not let go of the children, who are now 6 and 5 years old (Korean age).

The last time Sichi saw them was about a year ago during a supervised visitation granted by a local court. It has been three years since he has lived with his kids.

Out of frustration, he started walking on a portable treadmill out in the open in October. He demonstrates in Gangnam, Yeouido and various other spots in Seoul in a desperate effort to catch people’s attention.

The treadmill symbolizes the frustrating situation he is in, where he tries everything possible to bring his children back but sees no progress.

Sichi’s wife could not be reached for comment.

Sichi is among six American parents whose Korean spouse has unilaterally taken their children to Korea and has refused to return them between 2020 and 2021, according to the US State Department’s annual report on international parental child abduction that was published in September.

Half of the parents were unable to retrieve their children even after obtaining legal custody and the right to recover them through legal proceedings, largely due to “delays in law enforcement,” it said.

The report categorizes Korea as one of the countries deemed non-compliant with the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, with the cases remaining unresolved for a year and seven months on average.

Signed by 93 countries on Oct. 25 in 1980, the Hague abduction convention is a multilateral treaty aiming to secure the prompt return of children under the age of 16 who have been wrongfully removed from their country of habitual residence. Korea signed it in May 2012 and the following year enacted a new act to deal with international parental child abduction cases.

Why the inaction?

Despite the convention, local law and court orders mandating an abductee child’s return to its custodial parent overseas, forceful enforcement rarely takes place in South Korea.

Local legal experts point to a lack of compulsory regulations that apply to the court’s child recovery orders.

“There is a law called the Civil Execution Law, which stipulates that law enforcement officials can forcibly take movable assets away from a debtor and deliver them to his or her creditor. This law, however, does not apply to the retrieval of abducted children,” said Han Jang-hun, a senior staff attorney of law firm Win & Partners.

With no such rule in place, enforcement officials tend to play a passive role in bringing the abductees to foreign parents with custody, he said.

The only viable option for foreign custodial parents to retrieve their abducted children in Korea at this point is “indirect enforcement,” he continued, like getting the court to order fines and detentions to push the Korean parents to give up the child.

But what if they continue refusing to let go of the kids, even with those penalties?

That is what the former wife of Jay Sung, a 42-year-old Korean American living in Washington, has chosen to do, Sung told The Korea Herald.

Sung's former wife -- who took their 6-year-old son Bryan to Seoul in June 2019 when they were in the midst of a divorce -- has already received court-ordered penalties, including fines and detentions. But she is still refusing to return his son, he said.

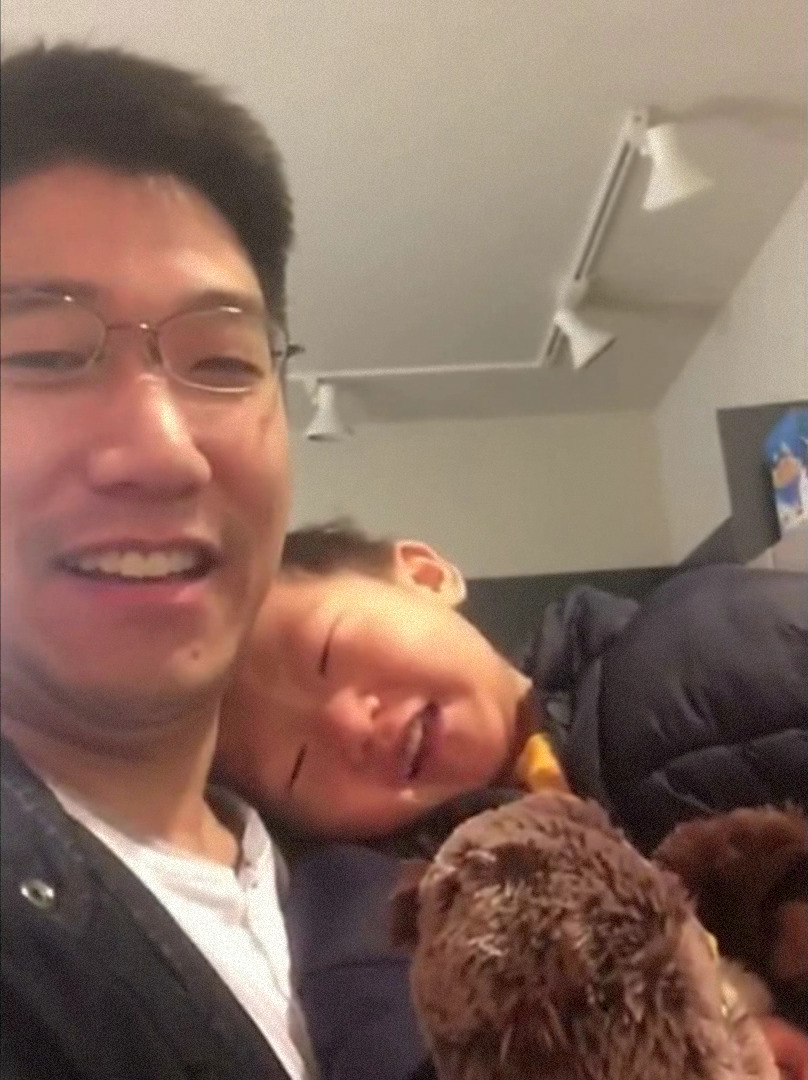

|

Jay Sung and his 6-year-old son Bryan. Sung, despite winning full legal custody of his son, still has not received Bryan from his ex-wife in Korea. (Courtesy of Sung) |

Sung was granted sole physical custody of the child by the Washington State Court in December 2019, and the Seoul Family Court ordered his ex-wife to return the child in accordance with the Hague convention in December of that year. The return order was later upheld by both the High Court and the Supreme Court in 2020 and 2021.

“Currently, Bryan’s mother and her family are laughing the court orders off. Nothing really happens after insignificant fines and a short detention,” he said.

Stressing that child abduction is not a “mom versus dad problem,” Sung called for stricter legal frameworks that guarantee the return of children who were wrongfully removed from their home country by a noncustodial parent.

“It should be very tempting to see this issue as a ‘mom versus dad’ problem because it’s less complicated that way. However, this is rather an issue of ‘legal versus illegal.’ The child who is taken out of his jurisdiction has to be brought back,” he said.

Sichi took issue with Korean officials’ prioritizing the opinion of the abductee children over the court’s decision on their custody.

“The officials ask children to choose between mom and dad. (…) We don’t let a 3-year-old kid make life-altering decisions,” he said. "If your children say they don’t want to go to school, it’s nice to hear their opinions, but adults are the ones who can make the right choices."

In America, court officials conduct a child recovery process in which child psychologists help abducted children who are at risk of serious emotional and psychological problems understand court decisions, encouraging their voluntary return to a country where a parent with custody lives. In France, children’s court-ordered return to their country of habitual residence is enforced without regard to their opinions.

To a query from The Korea Herald, a Justice Ministry official said it is largely on “humanitarian grounds” that Korean enforcement officials find it hard to forcibly separate a child from the abducting parent, particularly when the child insists on staying with the said parent.

"The government reviews all possible measures to carry out its statutory duty under the (Hague) treaty. We have been talking with the local court about the possibility of revising court rules to strengthen the law enforcement process regarding parental child abduction cases."

Adding a clause to the civil law stipulating the return of the abducted children is one of the options on the table, the official said.

Japan, which joined the Convention in May 2013, revised its civil law to include regulations on parental child abduction in 2019 after it was removed from the US State Department's list of countries showing a pattern of noncompliance with the treaty, according to news reports.

This week, the special adviser on children’s issue to the US State Department, Michelle Bernier-Toth, held a meeting with the ministry officials in Seoul to discuss unresolved child abduction cases, among other issues.

"Preventing and resolving cases of international parental child abduction is one of our top priorities. The department engages actively with parents, stakeholders, and countries across the globe, to identify, resolve, and prevent IPCA cases. South Korea is a key ally of the US. We have confidence that our Korean counterparts will work with us to resolve this issue," said Katherine Tarr, deputy spokesperson of the US Embassy in Seoul.

The Justice Ministry official said "the government is fully aware of the US State Department’s concerns about the country’s lack of enforcement of return orders in abduction cases. We are trying to come up with measures to deal with the unresolved (Hague) convention cases in Korea.”

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)