|

US presidential candidates Hilary Clinton(left) and Donald Trump |

While both Republican candidate Donald J. Trump and Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton pledge greater infrastructure investment that could create opportunities for Korean businesses, they also advocate protectionism, signaling a change, if not a complete overhaul, of trade policies.

“Overall, the protectionist tone will be enhanced in (US) trade policies either way,” said Park Seon-hu, a researcher at Industrial Bank of Korea’s economic research institute. “If Trump wins the election, he is very likely to demand revisions to the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement due to the constant deficits from US trade with Korea.”

Trump has argued for a withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiation of the North America Free Trade Agreement, known as NAFTA, and the imposition of high taxes on imports from Mexico and China.

Clinton, who supported free trade during her years as secretary of state, has shown conditional opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade deal after some flip-flops.

Clinton is not forecast to take a sudden U-turn in current policies, but is expected to impose regulations on imports of some oversupplied goods such as steel, metals and chemicals, according to the researcher.

Clinton has also been calling for strong punishments on unfair trade practices conducted by other countries in a bid to protect American business’ interests.

“Anti-dumping lawsuits filed by the US would continue to increase, while pressure on the foreign exchange policies of China, Japan and Korea are expected to mount,” said an official at Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency’s office in Washington via email.

If the new US government moves to revise the FTAs and impose higher tariffs on its long-time trade partners, China may take retaliatory moves against the US, the KOTRA official said.

“In that case, there could be a trade war between the US and China,” he said. “Whoever wins, there will be more negative factors than positive ones for the Korean economy. The government will need to prepare measures to help minimize the damage to Korean businesses.”

|

Source: Korea Customs Service |

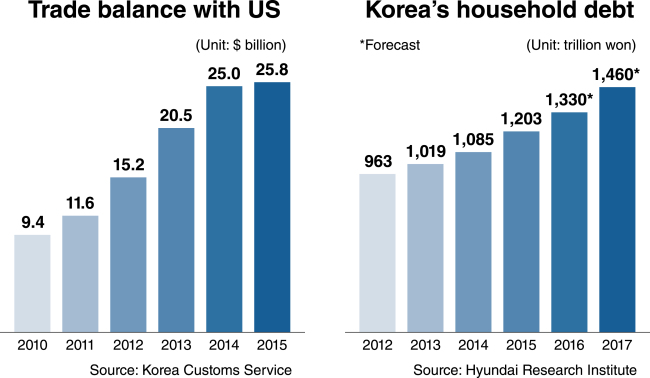

The US is the second-largest single market for Korean exporters. Since the Korea-US FTA took effect in 2012, the county’s trade surplus with the US constantly grew from $15.2 billion in 2012 to $25.8 billion in 2015, according to data by Korea Customs Service.

Another external risk for the Korean economy is rate increases by the Federal Reserve.

Already, there are concerns about the impact of future US rate hike on the debt-ridden household economy, as many commercial banks here moved to raise mortgage interest rates since the Fed sent a strong signal that it would raise its key rate band in December.

|

Janet Yellen, chair of the Federal Reserve |

Theoretically, a US rate hike is expected to force the Bank of Korea to hold its base rate at the current 1.25 percent a while longer. If foreign investors start pulling out their money from the Korean capital market as they go after a higher rate, the BOK would have to consider raising its rate to help stabilize financial markets.

“In theory, when talking about the low base rate, we should consider the risks of capital outflow,” said BOK Gov. Lee Ju-yeol at a press conference in September. “A US rate increase and resulting strong dollar could raise capital outflow risks in emerging markets, and therefore Korea can consider raising the lowest effective level.”

If the Korean central bank follows the US in the long run, the country’s massive household debt might turn into a “time bomb” as many pundits warn here.

As of the second quarter of this year, the aggregate household debt stood at about 1.26 quadrillion won, spiking 126 trillion won from a year earlier.

Hyundai Research Institute said in a recent report that the total debt would reach 1.33 quadrillion won by the end of the year, and it is forecast to rise 9.8 percent next year.

“Due to the all-time-low benchmark interest rate, households are relying on leveraging as borrowing costs are lower than before,” the report said. “Since income growth has been too sluggish, some low-income households are borrowing loans from banks to pay living costs.”

Household debt was pointed out as the biggest risk to the country’s financial system in a survey by the BOK of around 80 financial experts last week.

As much as 70 percent of the experts cited the debt issue, while 51 percent mentioned US monetary policy.

“If the Fed views the US economy in a positive manner in December, the pace of rate hikes can be faster than expected,” said Park Jong-kyu, a researcher at Korea Institute of Finance. “This will cause burdens on indebted households and companies to surge.”

Soured diplomatic relations with China are also putting the Korean economy at risk, since the nation’s largest trading partner may take retaliatory measures against Korean businesses.

Korea’s ties with China had been more optimistic than previous governments during the first years of the Park Geun-hye government, until before Korea announced in July the deployment of a US advanced missile defense system THAAD in Seongju, North Gyeongsang Province, which China has been strongly opposed to.

Korea’s exports to the country stood at $116 billion in 2015, accounting for about 26 percent of total exports.

Right after the announcement, performances of Korean entertainers there were abruptly canceled and broadcasting of new dramas featuring Korean actors was postponed. Some even raised worries that Chinese consumers could boycott Korean cosmetics and other products.

With heavy reliance on the Chinese markets, leading South Korean businesses are also suffering from tighter import regulations imposed by the Chinese government while losing competitiveness in major industries.

Financial jitters in Europe are also persistent risks for the Korean economy.

Britain’s decision to leave the European Union -- known as Brexit --by March 2017, the possibility of the European Central Bank tapering its quantitative easing and the eroding fiscal soundness of some European banks are likely to influence the international financial market as well as the Korean market, where a third of shares are owned by foreign investors.

“There are a number of jittery factors happening at the same time in Europe,” said Lee Sang-won, a researcher at Korea Center for International Finance. “In the mid- and long run, the EU’s solidarity would get weaker while the ECB’s monetary measures become less effective, which will lead to dire market outlook.”

By Song Su-hyun (song@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)