|

A signage for loans to households and micro-business owners is seen at a commercial bank branch in Seoul. (Yonhap) |

SEJONG -- South Korea’s benchmark interest rate has been set at an all-time low of 0.5 percent per annum for 10 months since May last year, as the central bank tries to prop up a lackluster economy that has faltered in the wake of the novel coronavirus.

The record-low rate could benefit many households and micro-business owners who resort to financial loans in this unexpected situation.

But the Bank of Korea will have no choice but to conduct rate hikes eventually on a mid-term basis, given that the low-rate era causes inflationary pressure, which would undermine private consumption.

Under such a scenario, a large portion of outstanding loans could pile up. Soured loans could threaten soundness of financial services firms including commercial banks and pose high risks to the overall economy.

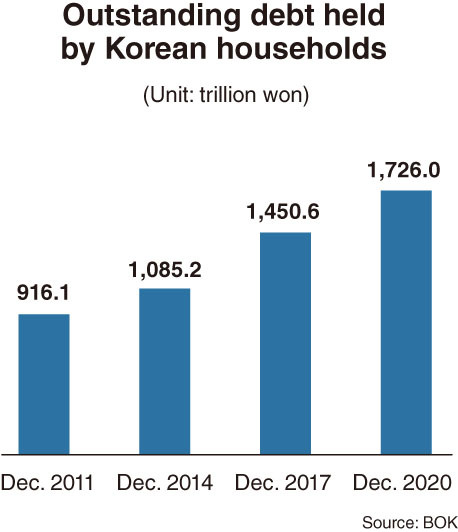

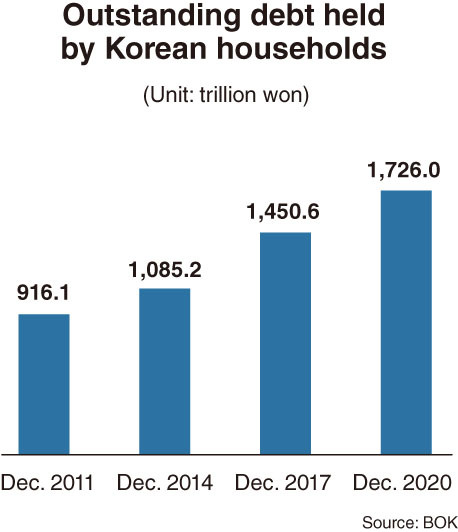

According to the Bank of Korea, the outstanding household debt -- the total of financial loans plus credit card-based payment services extended to households -- came to an all-time high of 1,726 trillion won ($1.52 trillion) as of December 2020.

|

(Graphic by Kim Sun-young/The Korea Herald) |

The debt held by the household sector surged by 18.9 percent in only three years from 1,450.6 trillion won in December 2017 -- or by 59 percent from 1,085.2 trillion won in December 2014 and 88.4 percent from 916.1 trillion won in December 2011.

The benchmark rate has stayed under 2 percent -- ranging between 0.5 percent and 1.75 percent per annum -- during the Moon Jae-in administration that began in May 2017. It triggered a nationwide fever of purchasing apartments by taking out mortgages or investing in stocks via credit-based borrowings.

The fever accelerated in the last one or two years, fueled by fears that residents might never be able to purchase an apartment if they wait any longer.

More and more people have also opened stock trading accounts as the nation’s main bourse Kospi continued to advance to renew record-highs despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The stellar rise was also seen as partly due to the provisional ban on short selling by the financial authority to block reckless share dumping. Other new individuals who joined as investors in the capital market are estimated to have been spurred by their frustrations with skyrocketing real estate prices.

But concerns are growing as commercial banks are poised to scrap offering discounted lending products following climbing rates on government bonds.

A recent move is that some major banks have halted -- or scaled back -- offering of prime rates to borrowers such as salaried people and civil servants, or to households applying for mortgages.

NH Bank has decided not to provide customers with mortgages at prime rates -- in which lending rates had gone down by 0.2 percentage point -- any longer. Shinhan Bank has conducted a similar measure, by slashing benefits, over formerly discounted rates on some mortgage products.

Woori Bank has suspended prime rate discounts of between 0.3 and 0.6 percentage point, which had been offered to customers for credit-based loans.

These moves could suggest that the banking sector is betting on an economic recovery and subsequent hikes of the benchmark rate by the BOK.

In the wake of the suspension of interest discounts, customers will have to bear higher interest burdens when they apply for rollover of loans or sign new borrowing contracts.

Should the central bank move to raise the base rate, it would be more worrying for those who have taken out loans on floating rates. Past cases have shown that when the US conducts rate hikes to normalize the interest level, Korea is likely to follow suit to prevent capital outflow.

“As a large portion of households and small business owners are saddled with debt, preemptive guidelines by the government are urgent before the benchmark rate is hiked,” a brokerage firm-based analyst said.

“Without a soft landing of the record-high household debt, the economy would face a variety of hurdles,” he said. “Due to the pandemic, many households have already lost capacity to repay their debt from unemployment or worsened earnings.”

By Kim Yon-se (

kys@heraldcorp.com)