Concerns have been raised that Korea’s long-term fiscal soundness will be undermined by President Moon Jae-in’s policies that are set to be accompanied by a sharp rise in government spending.

His administration has made clear it will expand annual fiscal expenditure at a faster pace than the country’s nominal economic growth rate, which is equal to real growth rate plus inflation.

On his campaign trail, Moon pledged to increase government spending by at least 7 percent annually throughout his five-year presidency to carry out his income-led growth policy.

Since his inauguration in May, the new government has rolled out measures designed to increase welfare benefits, create more jobs mainly in the public sector and help small businesses pay minimum wages, which are set to rise next year.

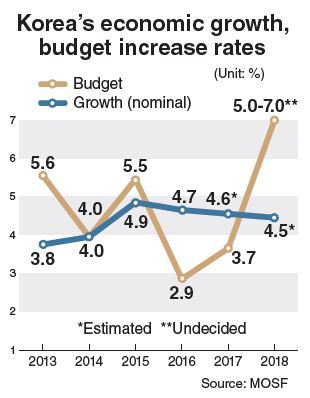

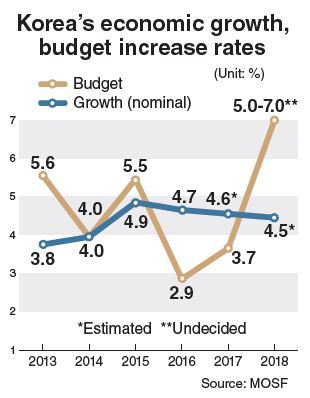

Korea’s national budget rose 2.9 percent last year and 3.7 percent this year, with its nominal growth rate standing at 4.7 percent and 4.6 percent, respectively, in the corresponding years, according to data from the Ministry of Strategy and Finance.

The ministry is working on a budget plan for next year, which will be submitted to the National Assembly in September.

Ministry officials suggest the 2018 spending plan will call for a more than 5 percent increase from this year’s budget set at 400.5 trillion won ($353 billion).

The new administration’s fiscal policy departs from previous efforts to prevent fiscal conditions from deteriorating.

A five-year fiscal management plan set up last year by the administration under Park Geun-hye, Moon’s predecessor, capped the fiscal spending increase rate at an annual average of 3.5 percent for the period between 2016 and 2020.

Under the plan, the ratio of national debt to gross domestic product was to remain at 40.7 percent in 2020, little changed from 40.4 percent in 2017.

At the time, Finance Ministry officials forecast the ratio would reach 62.4 percent by 2060, if the welfare system was kept at the current level.

But a report released by the National Assembly Budget Office last year predicted the figure could rise to 151.8 percent. It warned that the continuous rise in fiscal spending might not be covered by issuing state bonds from 2033, putting the government at the risk of financial collapse.

The Moon administration has said it will be possible to fund his welfare and employment programs, which are estimated to cost 178 trillion won over the coming five years, without incurring additional debt.

It plans to secure some 60 trillion won in what it hopes will be a natural rise in tax revenues and 95.4 trillion won through the readjustment of fiscal expenditures.

A draft tax code revision announced by the government last week is expected to bring 5.47 trillion won in additional revenues annually by raising rates applied to wealthy individuals and large profitable companies.

The funding plan is deemed by many as too optimistic.

But the government’s reluctance to get more workers to pay taxes and raise value-added taxes would limit room for collecting more revenues, leaving it with no choice but to issue debt.

Korea has recorded annual fiscal deficits over the past several decades except for five years -- 1987, 1988, 2002, 2003 and 2007. Such occasional surpluses were due to an unexpected increase in revenues rather than curbing fiscal spending.

Even if the new administration’s funding plans manage to cover the costs of Moon’s welfare and employment programs, burdens arising from them will be carried forward to the following governments.

“It would be impossible to curtail spending programs being introduced by the Moon administration,” said Yoon Chang-hyun, a professor of finance at the University of Seoul, adding they would force succeeding administrations to continue to implement expansionary fiscal policy.

An economist at a private research institute, who asked not to be named, said the new government could feel free to increase fiscal spending to finance popular programs due to past efforts to maintain fiscal health, but unrestricted expenditure would leave burden on future generations.

Arguments have been growing that the country needs to enact a law aimed at guaranteeing fiscal soundness as it sees structural and obligatory parts of government spending expanding at a steep pace.

The previous administration submitted a bill aimed at consolidating fiscal soundness to the parliament last year.

But lawmakers turned it down out of concerns that the proposed law would result in curbing welfare spending.

Experts agree fiscal roles need to be strengthened in coping with low birth rates and population aging, settling economic and social polarization and preparing for a new wave of industrial innovations.

But unprincipled spending swayed by political considerations and social sentiments would result in degrading the budget and fiscal management system, they say.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)