President Moon Jae-in’s government is seen to be moving to decouple security and historical issues from South Korea’s economic ties with China and Japan.

Moon expressed such intention during phone talks with his Chinese and Japanese counterparts a day after being sworn in last week.

|

(Yonhap) |

He asked Chinese President Xi Jinping to lift restrictions and sanctions imposed on South Korean people and businesses apparently in retaliation for Seoul’s hosting of a US anti-missile shield, called the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, while saying he understood Beijing’s concern.

“Moon’s remarks can be interpreted as a request to separate the THAAD issue from economic matters,” said Lee Jun-sang, an economics professor at Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul.

It has yet to be seen whether Xi, who was said to have reiterated China’s objection to the THAAD deployment during the phone talks, will respond affirmatively to the request from the new South Korean leader.

Throughout his election campaign, Moon had insisted that the new Seoul government should be given time to review and, if necessary, reconsider the deployment of the US missile defense system.

Observers say it will be hard for Moon to roll back the deployment at the risk of weakening the Seoul-Washington alliance, which he described as the foundation of South Korea’s diplomatic and security policies during his phone conversation with US President Donald Trump on the day he took office.

The conflict over the THAAD deployment may be expected to be resolved in a context of “big deals” between the US and China.

During his phone talks with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Moon said most South Koreans were against an agreement reached by his conservative predecessor’s government with Tokyo on settling the issue of Japan’s pre-1945 wartime sexual enslavement of Korean women.

But he also noted historical issues should not hinder the two countries from strengthening practical cooperation to build a future-oriented partnership.

The Abe administration has been tempted to use economic leverages to put pressure on South Korea in the course of diplomatic discords.

In January, Tokyo suspended talks with Seoul on reopening a currency swap line in protest against the installation of a statue symbolizing Korean women forced into sexual slavery in the South Korean city of Busan.

Financial officials here are worried China may also refuse to extend a Seoul-Beijing swap deal worth $56 billion, which is set to expire in October, in yet another reprisal against the THAAD deployment.

A report released early this month by the Hyundai Research Institute, a private think tank, forecast Beijing’s retaliatory moves would cost Korea 8.5 trillion won ($7.54 billion) in economic losses this year, mostly in the sectors of tourism, distribution and cultural contents.

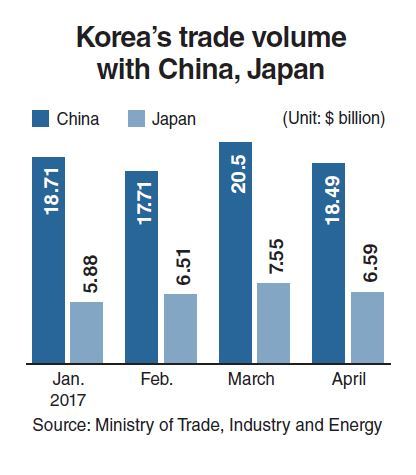

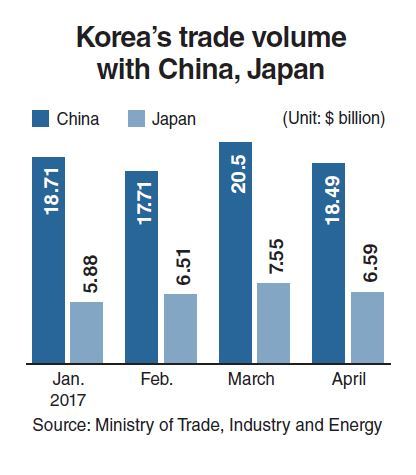

But the country has seen its exports to China increase over the past months despite Beijing’s toughened regulations, showing Chinese manufacturers still rely heavily on intermediary goods from Korea.

The bilateral free trade agreement between the two countries, which took effect in 2015, has also served to keep Beijing from going against the rules-based trade in an outright manner.

Han Jae-jin, a HRI researcher, said it is necessary to facilitate additional negotiations on opening the service sector, which is not covered by the present trade accord between Korea and China.

Prolonged diplomatic disputes over historical and territorial issues have held back Korea and Japan from realizing the full potential of trade and investment between them.

Economists here note the two neighboring countries share interests in cooperating to deal with low birthrates, aging populations, a new industrial revolution and rising protectionism across the globe.

Chung In-gyo, an economics professor at Inha University, said efforts should be stepped up particularly to conclude a bilateral trade pact to cope with the changing global economic environment.

In a larger context, Korea and Japan can work together with China for tripartite cooperation in cautioning against and lessening the negative effects of protectionism pursued by President Trump.

Top financial and monetary policymakers from the three countries vowed to “resist all forms of protectionism” in a joint statement issued after their meeting on the sidelines of an annual gathering of the Asian Development Bank early this month.

They agreed that “trade is one of the most important engines of economic growth and development,” the statement said.

The language was stronger than a statement released by the financial and monetary chiefs of the Group of 20 economies in March, in which they dropped the line against protectionism apparently in the face of objection from the US.

But China embarrassed the finance ministers and central bank governors from Korea and Japan by sending its vice finance minister and a working-level official from the People’s Bank of China to the meeting.

Commentators here said such behavior could be seen as a “childish” expression of China’s sense of superiority that would serve little to set up the country as a respectable global leader.

They indicated China should have behaved better than notifying Korea and Japan of the change of its participants just a day before the meeting as the rejection of protectionism is a crucial issue for the world’s second-largest economy and biggest exporter, too.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Korea, don't repeat Hong Kong's mistakes on foreign caregivers'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050481_0.jpg)

![[KH Explains] Why Yoon golfing is so controversial](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050608_0.jpg)