An organ of the Chinese Communist Party warned last week South Korea would pay the price for agreeing with the US to launch a vice-ministerial consultative body tasked with studying how to improve the implementation of Washington’s extended deterrence against evolving nuclear and missile threats from North Korea.

The Global Times said in an editorial Seoul should ask itself whether it could afford to push for the establishment of the envisioned mechanism, which the newspaper suspected might transform into an Asian version of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization that would be postured against China and Russia as well as the North.

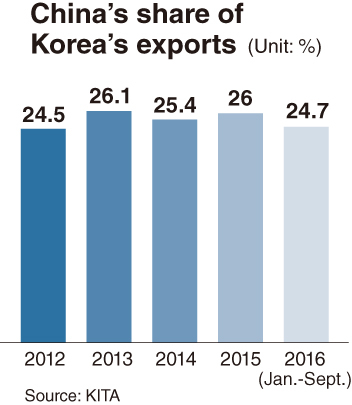

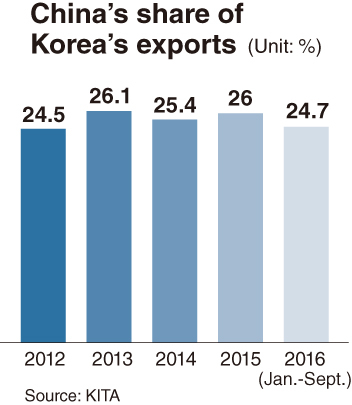

The editorial went the extra mile to point out South Korea’s external economic vulnerabilities, including reliance on China for about a quarter of its trade volume.

It appeared to be making yet another veiled threat of possible economic retaliation against Seoul for moves annoying Beijing.

Concerns were raised here in July that China might get South Korea to pay the economic price for allowing the US to deploy an advanced missile defense battery on its soil.

While expressing strong displeasure with Seoul’s decision that it sees as infringing on its strategic security interests, Beijing has so far refrained from mentioning possible retaliatory measures.

Experts here see little possibility of China going for significant economic retaliation for South Korea’s diplomatic and military decisions that displease it, noting such a response may also have negative consequences for its own economy and international reputation.

South Korean exporters’ heavy dependence on China certainly leaves them particularly vulnerable to trade restrictions by Beijing. Such measures, however, could boomerang to hit some Chinese manufacturers in areas such as liquid-crystal displays and semiconductors, which still depend on intermediary goods and equipment imported from South Korea.

China may also be concerned that retaliation against South Korea in disregard of international standards would hamper its efforts to be granted a market economy status by western economies at the end of this year as understood when it joined the World Trade Organization 15 years ago. Its unreasonableness could loom larger as South Korea is one of a few major economies with which China has concluded a free trade accord.

What makes it riskier for South Korean exporters to remain heavily reliant on China is the shift of focus in the world’s second-largest economy and rapid technological advancement by their Chinese competitors, economists note.

As its economy becomes more sophisticated, China has undertaken multiple stages of production in-country rather than remaining a final assembly base for components manufactured in South Korea and other countries. To facilitate this transition, China last year announced a plan named “Made in China 2025,” which is designed to transform the country into a world manufacturing power.

As a result, many South Korean companies have lost ground in the Chinese market and vied with Chinese rivals for global market shares.

South Korea’s exports to China fell by 9 percent from a year earlier in September, marking the 15th consecutive monthly decline, according to data from the Korea International Trade Association.

China’s share of South Korea’s exports, which rose from 10.7 percent in 2000 to 26 percent last year, slid to 24.7 percent in the first nine months of the year.

China also seems to be increasing pressure on South Korean exporters in a less conspicuous way through nontariff tools. According to Chinese quarantine data cited by the Beijing branch of the KITA, 61 shipments of South Korean food and cosmetics products were rejected by China’s customs authority in August, soaring from five in the previous month.

Economists here also worry that heavy dependence on China may lead South Korea to be hit harder by a slowdown or turbulence in the Chinese economy, which grew by 6.7 percent in the third quarter on the back of stimulus measures that critics say come at the cost of much-needed structural reform.

According to analysis by Choi In, a professor of economics at Sogang University in Seoul, South Korea’s economic cycle has followed a course decoupled from global economic trends since the 2000s. He attributed this phenomenon to the South Korean economy’s growing and heavy dependence on China over the period.

“The utmost task facing the Korean economy is to reduce its excessive dependence on China,” he said.

Observers note economic overreliance on China has resulted in Beijing becoming heavy-handed with Seoul in dealing with other matters between them, including illegal operations by Chinese fishing boats in the waters off South Korea’s west coast.

In a departure from the previous protocol, China sent working-level officials to a National Day reception hosted by the South Korean embassy in Beijing last week, while a South Korean vice foreign minister attended a similar event at the Chinese embassy in Seoul in September.

“What this means is that China just makes little of us,” a participant at the Beijing reception was quoted by a South Korean newspaper as saying.

Some observers say South Korea’s economic dependence on China may have led Chinese officials to feel it easier to express their discontent with Seoul’s moves to strengthen security partnership with Washington in such a non-diplomatic manner.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)