Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes often gradually show symptoms of depression as their illness progresses.

The link between diabetes and depression had long been suggested, but not proven, by scientists as far back as the 1680s when renowned English doctor Thomas Willis first stated the hypothesis.

A team of Korean and American scientists, led by Dr. Lyoo In-kyoon of Ewha Brain Institute and Division of Life and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Ewha Womans University, corroborated this through cross-sectional research. They studied and compared patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, or T1DM, who had depressive episodes, with other groups including people without T1DM and with T1DM but were not depressed.

Dr. Lyoo and Dr. Yoon Su-jung of Catholic University of Korea’s College of Medicine joined Dr. Alan M. Jacobson of Joslin Diabetes Center, and Dr. Perry F. Renshaw at the University of Utah Department of Psychiatry and the Brain Institute for this study, supported by Korea’s Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

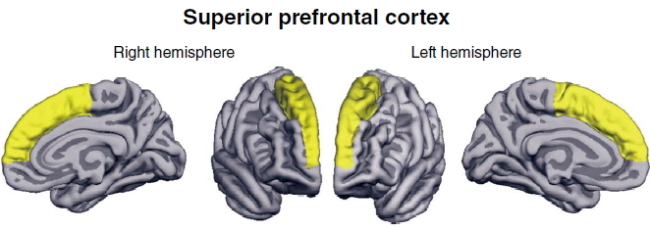

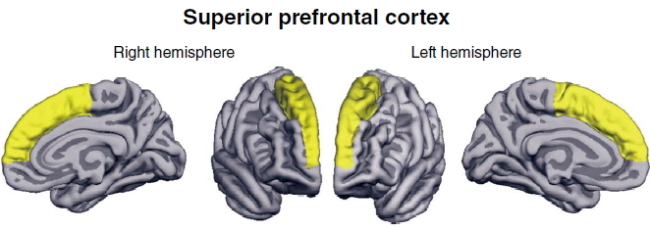

Their results showed that the superior prefrontal cortex of patients had been negatively affected by T1DM, which contributed to “the increased risk for comorbid depression,” the group said in the Archives of General Psychiatry, a journal on psychiatry, neuroscience and behavioral science.

The superior prefrontal cortex is the upper front part of the human brain, located below the forehead, whose main functions include managing emotions and memories.

Lyoo’s team reported that T1DM can damage this brain region through a thinning of the superior prefrontal cortex, which can undermine its “executive function and cognitive performances.”

“We found that patients with T1DM, relative to healthy control subjects, had thinner cortical thickness in the superior prefrontal cortex region,” Lyoo said in the journal.

“We have here provided the first neuroanatomic evidence of prefrontal cortical deficits as brain correlates of comorbid depression in T1DM.”

Also, its neuroanatomic images showed that patients with weak glycemic control system, one of the causes of diabetes, had greater deficiency in their superior prefrontal cortex.

Lyoo said that he hopes that this latest discovery could provide a foothold in developing “mechanism-based strategies” for treatment and prevention of T1DM-based depression.

However, his team suggested that it needs to carry out a different type of research to further corroborate its evidence of the link between T1DM and depression.

“Future longitudinal studies will be needed to confirm this brain-based and potentially self-perpetuating cycle between T1DM and depression,” Lyoo said.

The team conducted cross-sectional studies using high-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which is a short-term-based research, as compared to longitudinal studies which take a longer period of time.

The Korean government has been expanding its support for research on chronic diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and diabetes as ages rapidly society.

Diabetes occurs when the body is susceptible to high blood glucose due to resistance to insulin, a sugar regulating hormone.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is most common among adults as they exercise less and gain more weight while getting older due to work and stress, while T1DM is found among children and teenagers, only accounting for 10 percent of all patients diagnosed with both types globally, according to the Science Ministry and the World Health Organization.

A growing number of young adults and children are also being diagnosed with type 2 due to obesity problems, health officials warned. The prevalence rate of diabetes in Korea stands at around 8 percent.

Some 3.2 million Koreans were suffering from diabetes as of the end of 2010, with the number expected to exceed 5 million in 2030 and reach 6 million by 2050, the Korean Diabetes Association said.

By Park Hyong-ki (

hkp@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Korea, don't repeat Hong Kong's mistakes on foreign caregivers'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050481_0.jpg)

![[KH Explains] Why Yoon golfing is so controversial](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050608_0.jpg)