Budget planners, politicians in head-on clash over tax cuts for the rich, corporations

Billionaire investor Warren Buffett’s recent call for higher taxes on the U.S.’s super rich drew much attention from Koreans.

Korean media also reported moves by wealthy Europeans to follow Buffett’s lead by offering to pay more taxes to help cut the mounting debt of their governments.

Many commentators here have contrasted the initiatives by the American and European billionaires with what they regard as rich Koreans’ lukewarm attitude to assuming more social responsibility. Some also say a lesson should be drawn from their example in settling the long-standing discord here over whether to cut taxes for the wealthy.

“My friends and I have been coddled long enough by a billionaire-friendly Congress,” Buffett said in a New York Times opinion piece in August, with his line later quoted by President Barack Obama to back up his call for spreading the pain when drafting a plan to cope with the mounting U.S. deficit.

What differentiates the tax debate here from the U.S. is that lawmakers have pressed the government to scrap the plan to reduce taxes on the rich and corporations. Over the past months, politicians and state budget planners have engaged in a bruising confrontation over whether to lower top rates of tax on personal income and corporate profits next year.

In December 2009, the National Assembly put a two-year moratorium on the lowering of top income and corporate tax rates from 35 percent to 33 percent and from 22 percent to 20 percent, respectively. Lawmakers, however, have recently pressed the government to scrap the tax cut plan, which will affect people making more than 88 million won ($82,200) per year and companies with annual profits of more than 200 million won. Members of the ruling Grand National Party have been as aggressive as opposition legislators in pushing intransigent budget planners to withdraw the plan.

Some observers expected the government to put forward an eased stance on the issue of tax cuts when it announces a set of measures to change the tax system this week. An official at the Strategy and Finance Ministry, however, flatly dismissed such speculation, saying, “We will continue adhering to our existing position.”

The ministry’s refusal to pay heed to demands from political circles heralds rough sailing ahead for parliamentary deliberations on tax-related laws and next year’s budget. GNP officials have vowed to draw up their own versions of bills to block tax cuts if the government insists on lowering rates as scheduled.

“We have no practical means to prevent the parliament from reversing the tax cuts scheme. But we have our own principles to abide by,” said the ministry official who requested anonymity.

On the surface, the confrontation between political parties and budget planners revolves around economic reasoning to justify their cases. Government officials say the rate cuts will induce companies to invest more and wealthy people to spend more money, boosting domestic demand and thus helping revitalize the economy. Party officials have countered that lower tax rates will only benefit the rich and big companies, saying the additional revenue raised by keeping current rates can be used to support small businesses and working-class people. A report from the parliamentary Special Committee on Budget and Accounts estimated the tax cuts would lead to an annual revenue loss of about 4.5 trillion won ― 3.9 trillion won in corporate tax and 600 billion won in income tax.

Political motives

Behind the arguments based on economic logic, however, are more immediate political motives, many observers note.

Both the ruling and opposition parties have regarded tax cuts as unacceptable at a time they are competing to come up with a flood of welfare measures to gain an upper hand in the run-up to the parliamentary and presidential elections next year. The main opposition Democratic Party recently put forward a plan to finance its welfare package, including free medical care, free school meals and free nursing of children as well as halving college tuition fees, which is estimated to cost 33 trillion won per year. According to the plan, the expenditure is to be covered with 12.3 trillion won saved from trimming state-funded projects, 6.4 trillion won from improving the efficiency of social safety networks and the largest proportion of 14.3 trillion won from revenues raised from the scrapping of the tax cut plan.

DP Chairman Sohn Hak-kyu claimed in a recent radio address that additional tax cuts for the wealthy would be a catastrophic policy, only increasing the burden on the poor and the middle class. Party floor leader Kim Jin-pyo pledged that the DP would push for the annulment of the planned rate cuts during the regular parliamentary session.

GNP officials apparently feel as much need to thwart the tax cut scheme as it tries to court voters’ support with welfare measures also forecast to cost trillions of won. The ruling party’s stance has been hardening since former Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon’s bid to block the opposition-controlled city council’s plan to provide free meals to all elementary and middle school students failed in August after less than a third of eligible voters ― required for the ballot boxes to be opened ― came to the polls. Oh’s fall in his anti-populism crusade, which came on the heels of a string of by-election defeats, pushed the ruling party to shed its conservative policies.

In the aftermath of the April 27 by-elections, in which opposition runners trounced ruling party contenders in key constituencies, GNP lawmakers agreed to roll back the planned tax breaks for the wealthy.

“Our position against additional tax cuts is firm and cannot be compromised,” said Rep. Kim Song-sik, deputy chief policymaker of the GNP. He insisted the government’s adherence to tax cuts is nothing but inertia lacking in logic and relevance.

“No matter what position the government is to take, there will be no change in the party’s stance,” he said.

Many observers note the GNP apparently feels further pressed on the tax issue in the face of the by-elections scheduled for Oct. 26, which will elect the successor to Oh who resigned after the referendum on free school meals was scuttled, and other local government heads.

Government officials have remained firm in their stance to push ahead with lowering rates as planned. In a meeting with members of the parliamentary budget committee last month, Finance Minister Bahk Jae-wan countered demands from political circles, saying consistent policies are important and that a reversal would be detrimental.

He indicated, in particular, corporate tax rate cuts would benefit more than 50,000 companies, only about 200 of which belong to the top 30 business conglomerates.

“Lower corporate tax rates will be beneficial mainly to small- and medium-sized companies,” he said.

Global trend

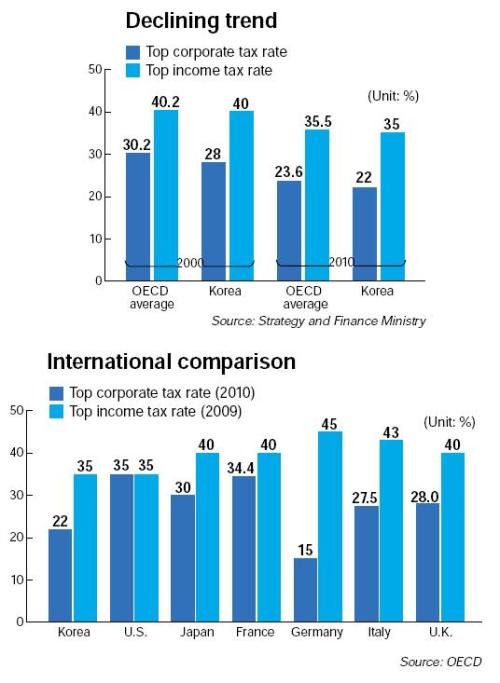

The minister also noted the global trend has been to lower income and corporate tax rates. Figures from his ministry showed top corporate tax rate in member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development declined from an average 30.2 percent in 2000 to 23.6 percent in 2010. The OECD average of top income tax rate fell from 40.2 percent to 35.5 percent over the same period.

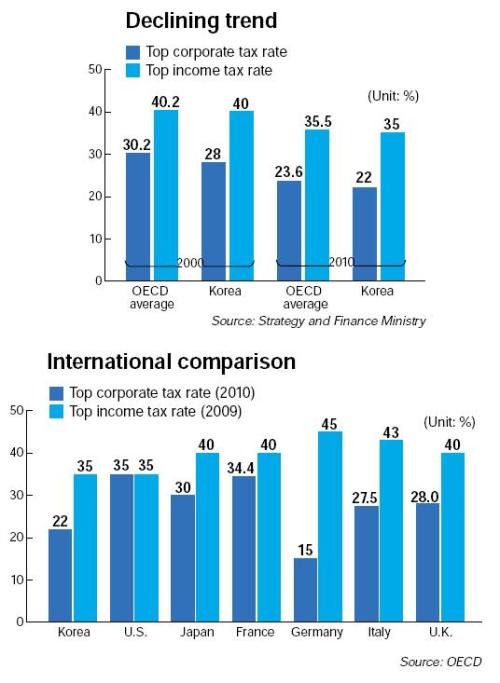

Ministry officials said a corporate tax cut is needed to enhance the competitiveness of local businesses, indicating Korea’s rate is higher than its competitors such as Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong which have their top corporate tax rates below 20 percent.

They also said that not cutting rates for about 130,000 people with higher incomes would seem unequal when people in lower income brackets already benefited from the lowering of rates under bills passed by the parliament in 2008.

A ministry official also raised questions about the wisdom of the political parties’ expenditure plans.

“According to the schemes of the major political parties, all additional revenues are supposed to be spent on populist programs,” he said. “It will only hamper the achievement of the balanced budget, erasing the virtuous cycle effect expected from tax rate cuts.”

Such a stance is harder than an earlier suggestion by Chief of Presidential Staff Yim Tae-hee that the implementation of tax rate cuts could be delayed beyond the start of next year, while the principle is retained.

Remnant of MBnomics

Some political commentators said the government’s firm stance may reflect President Lee Myung-bak’s wish to maintain the core component of his economic policy known as MBnomics coined after the initials of his given name, which was designed to boost the economy by lifting regulations on and strengthening support for businesses. They say a reversal would amount to the declaration of the death of MBnomics, which is already in tatters after its key measures including the privatization of public corporations have been jettisoned.

Ironically, Lee’s shift in policy to taking more care of the underprivileged over the past year has made the government’s stance vulnerable to criticism from political circles.

In his address marking Liberation Day last month, Lee pledged to strengthen efforts to promote shared growth of large and small businesses and reduce the widening gap between rich and poor. He further promised to achieve a balanced budget by 2013 a year earlier than scheduled in a measure to cope with the global debt crisis.

Critics say his pledges will assure no one unless his administration withdraws the planned tax breaks for the wealthy.

“(President Lee) should keep in mind that the first step toward what he described as eco-systemic development is the scrapping of tax cuts for the rich,” said DP lawmaker Noh Young-min in response to his address.

The confrontation over tax cuts is linked to the debate over the country’s fiscal health and tax burden. The government recently announced detailed measures to achieve a balanced budget by 2013 as promised by Lee. According to official statistics, the government debt stood at 359.6 trillion won at the end of 2009. But counting debt guarantees to state-funded agencies and debt owned by public corporations, the sum was estimated to soar to about 1,637 trillion won in 2009, according to GNP lawmaker Lee Hahn-koo. He expressed doubt the government could achieve the balanced budget as planned while pushing for tax cuts and spending a huge amount of money on the four river restoration project cherished by President Lee. Rep. Lee Yong-sup of the DP also said it was nothing but unrealistic optimism to aim to achieve the balanced budget by 2013 as the forecast for economic growth may be revised down.

There are varied views on the proper level of tax burden. The tax burden as a percentage of gross national product, which was 21 percent in 2007 under the presidency of Roh Moo-hyun, decreased to 19.3 percent last year as a result of the Lee administration’s tax cut policy. The OECD average stood at 26.7 percent in 2010.

“No one can be sure of the proper level, but I think it is desirable to reorganize the tax system with the goal of placing the tax burden ratio in the low 20 percent level,” said GNP deputy chief policymaker Kim.

Political circles remain cautious on the issue of increasing taxes including creating a wealth tax, which could be a double-edged sword for them.

While no ruling party lawmakers advocate tax increases, opposition legislators appear split on the matter. In a recent meeting of DP lawmakers, Rep. Chun Jung-bae called for a bolder and more positive approach to tax increase, suggesting the introduction of a wealth tax. But Rep. Kim Dong-cheol said the party should try to reflect public sentiment on the issue.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)