|

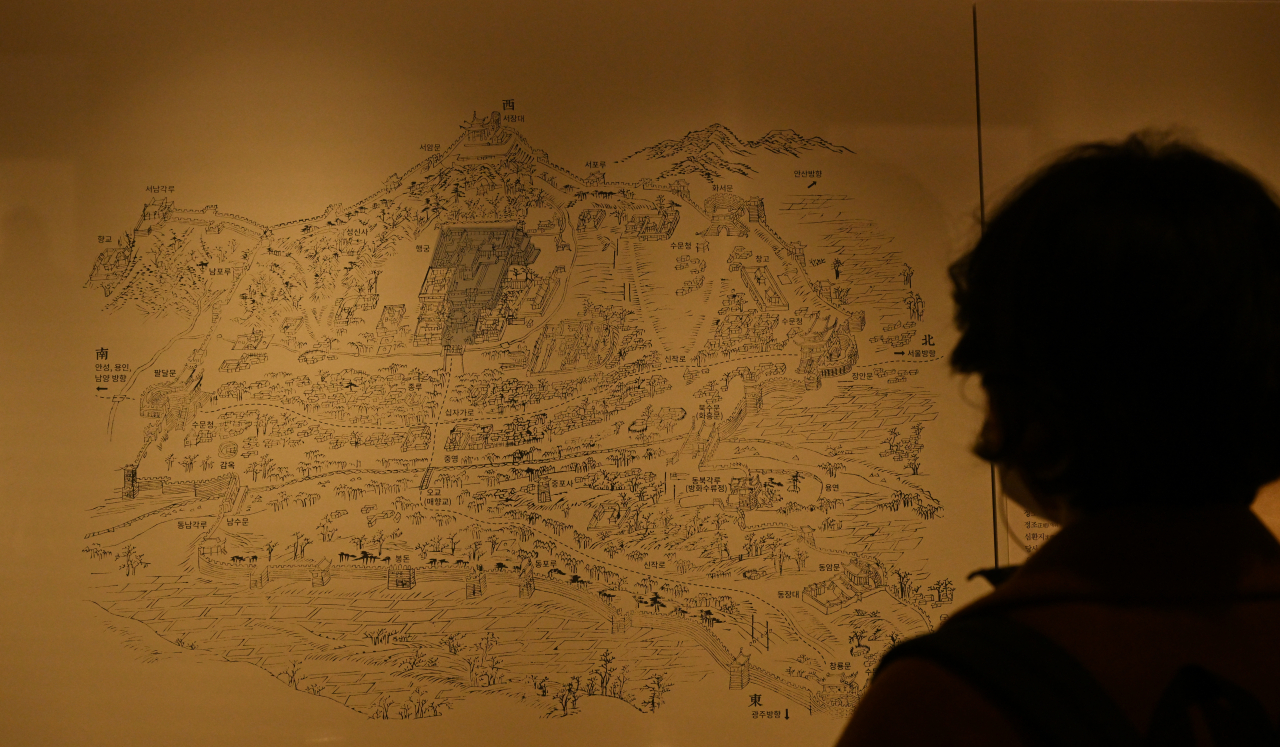

A visitor looks at the complete map of the Hwaseong fortress, through a copied page from the “Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" at the National Museum of Korea. (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald) |

When planning a new building, it is challenging to envision its potential collapse or destruction, along with the subsequent rebuilding process.

However, a remarkable example of resilience can be found in the 18th-century Hwaseong fortress in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province.

Despite enduring multiple instances of damage, the fortress, situated at the foot of the mountain Paldalsan, still proudly stands as it was built hundreds of years ago.

The secret behind its enduring presence lies in its "Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" (1801) construction records.

Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, Hwaseong was a project spearheaded by King Jeongjo (1776–1800), with the crucial design of the new city being undertaken by his adviser and scholar, Jeong Yak-yong.

Construction commenced on Jan. 7, 1784, with workers diligently carving stone materials from rocks. The monumental project involved the expertise of over 1,800 master craftsmen from 21 different fields. The endeavor reached completion on Sept. 10, 1786, followed by a celebratory banquet on Oct. 16.

King Jeongjo had specifically instructed for comprehensive records to be kept, documenting every aspect of the fortress's construction from its very inception.

Consequently, the exhaustive ten-chapter document comprising nine books, "Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" was completed, providing a meticulous chronicle of the fortress's original construction.

|

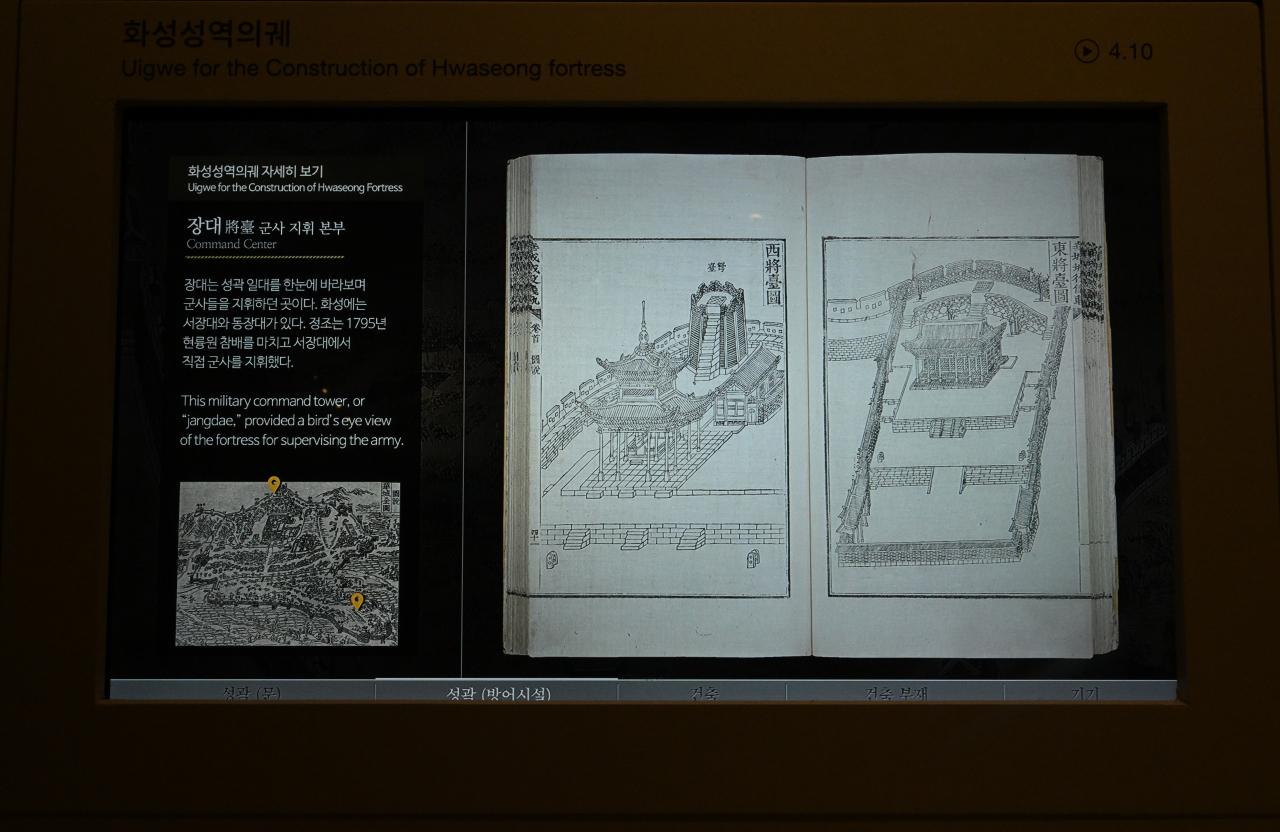

A digitized version of a page from the “Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" shows "jangade," or the military command tower of Hwaseong. (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald) |

The Joseon era witnessed the creation of numerous historical records focused on the royal kings, including notable works such as "Joseon Wangjo Sillok," or Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, "Seungjeongwon Ilgi," or Diaries of the Royal Secretariat and Uigwe, a compilation of royal ceremonies and protocols.

The term Uigwe derives from the combination of "euisik," meaning ceremony, and "gwebum," meaning example. The Uigwe served as a valuable guide for future generations, providing comprehensive insights into these important occasions.

Uigwe was inscribed in the UNESCO's Memory of the World register in 2007 for its historical significance as well as the aesthetic beauty in its depictions and illustrations. But its importance goes beyond royal affairs and encompasses records related to the construction of palaces and fortifications, as exemplified by the "Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe."

Among over 637 different types of Uigwe, 32 of them focus on the theme of construction, such as building new palaces, royal tombs, gates or pavilions, according to research done by Kim Dong-wook, a professor at Kyonggi University's architecture department. Among them, "Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" is the only one that focuses on the plan of a city with fortification.

Significant damage was inflicted upon certain sections of Hwaseong throughout history, spanning from the late Joseon era through the Japanese colonial period and up to the Korean War. Notably, during the Korean War, both the Janganmun and Changnyongmun gates suffered complete destruction.

Thanks to the detailed records found in the Uigwe, the original form of the fortress was successfully reconstructed when the initial restoration plan in 1964 was finally executed during the comprehensive five-year project between 1975 and 1979.

"The authenticity and preservation status of a historic building are vital factors for it to be appropriately acknowledged by UNESCO and designated as a World Heritage Site," Kim Jin-sil, a researcher at the National Museum of Korea, told The Korea Herald. "Upon inspecting the Hwaseong Fortress, the inspectors’ foremost concern was whether it had been faithfully restored to its original state."

The word-for-word and picture-by-picture descriptions found in the "Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" undoubtedly played a decisive role in its recognition, according to Kim.

However, there were obstacles encountered during the reconstruction process. As stated by the head of the architecture company who oversaw the project, one of the greatest challenges was the interpretation of the Uigwe, as they were written in Chinese characters. It took several years, until halfway through the project in 1977, for the city of Suwon to publish a translation.

|

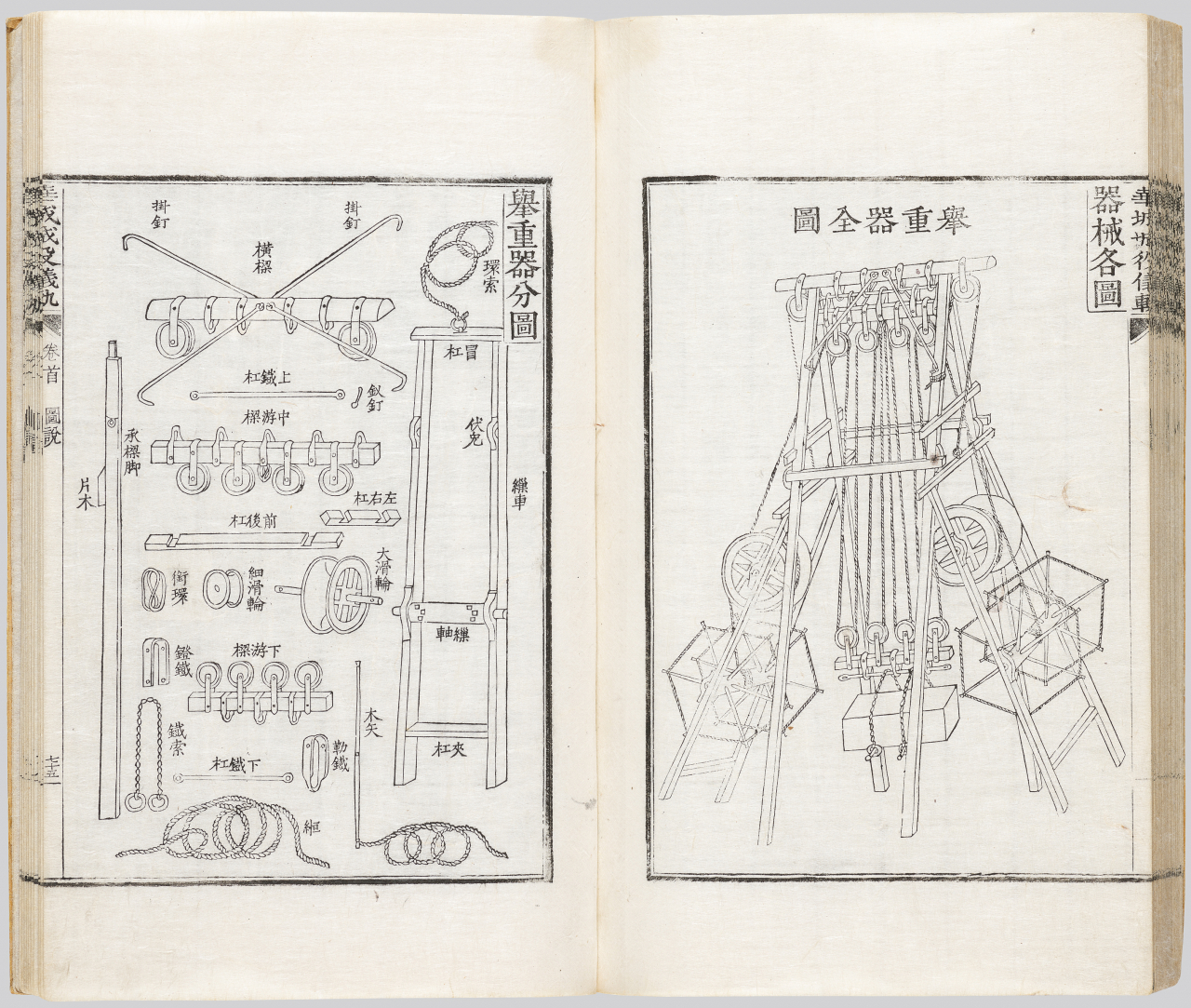

Inner parts and the finished piece of "geojunggi," a device developed to move and pile up heavy stones, depicted in “Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" (NMK) |

|

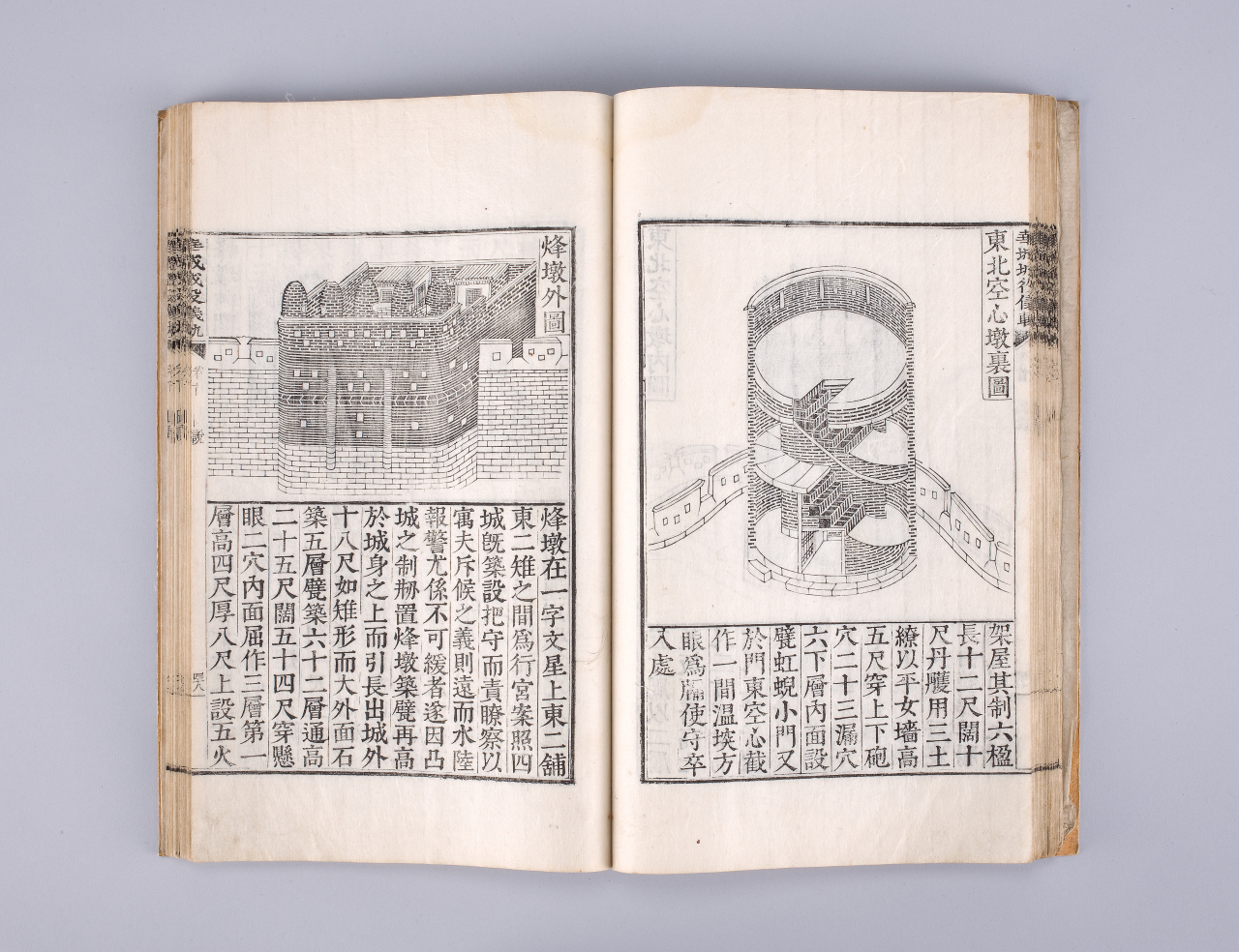

Drawings and descriptions of the Dongbuk Gongsimdon, or the Northeast Observation Tower, in “Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" (NMK) |

The Uigwe not only records buildings, but also provides comprehensive documentation of architectural materials and construction equipment. Detailed written descriptions are accompanied by illustrations, serving as invaluable resources for comprehending architectural engineering, transportation vehicles, and tools from that era.

Furthermore, the Uigwe records the total budget allocated for construction, including labor wages. For instance, 870,000 nyang -- approximately 60 billion won ($46 million) in today’s currency -- was spent on materials and labor. The most important skilled craftspeople were stonemasons, who earned daily wages of 4 jeon and 5 pun (approximately 32,000 won), along with 6 doe (around 10 liters) of rice.

The fortress walls were built from stone and bricks following the natural topography of the landscape. Numerous bricks were used in the "gongsimdon" watchtowers and in secret entrances called "ammun," in order to create structures that were both sturdy and attractive.

The Uigwe also contains written records of the names and instructions for innovative mechanical devices that were employed to efficiently lift and transport heavy stones.

The records in the Uigwe possess another remarkable characteristic in the form of their detailed illustrations. In addition to paintings that depict the various stages of construction, the Uigwe also includes diagrams. Since natural ingredients were used in the drawings, even after hundreds of years the pictures have not been discolored, and still exhibit the vivid hues.

“Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe" was designated a Treasure in 2016.

This is the sixth in a series of articles introducing well-known cultural artifacts from different periods in Korean history. -- Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)