|

“Jamchilla,“ a compound word of Rep. Lee Jae-myung and chincilla and ”Wonder Kun-hee“ are among the memes that capture the enthusiasm among the fandoms of the lawmaker and first lady. (A screenshot from online communities) |

"Fandom politics” is the latest buzzword in South Korean politics.

It made headlines after Park Ji-hyun, a former co-head of the Democratic Party of Korea’s interim leadership committee, said last month that she would change her party to become a party “for the public, not for fandoms.”

Park made the remarks as she criticized the culture that “defended the faults of their own while chastising political opponents for smaller problems” in politics.

She has resigned alongside other emergency steering committee members following a crushing defeat in the local elections last week. But the debate about “fandom politics” shows no signs of stopping soon.

Fandom means the state of being a fan of someone or something but also refers to a group of fans regarded collectively as a community.

In the book “Fanocracy,” author David Meerman Scott argues that fandoms are the most powerful marketing force in the world and no longer just for celebrities, but any business or nonprofit that chooses to focus on inspiring and nurturing true fans.

More often than not, the word is associated with pop culture such as TV shows or artists -- think of the Harry Potter fandom or BTS and Blackpink fandoms known as Army and Blink, respectively.

In recent months, however, the word has kept appearing in political discourse across the political spectrum.

While regular political supporters decide to support politicians who align with their political views, political fandoms alter their views to be more in tune with their favorite politicians, said Kim Nae-hoon, a media culture researcher and the author of “Radical 20s: K-Populism and the Political.”

“Fandom politics is when you keep adjusting your political views in line with the person you support, I believe,” he said.

“Having fans who are voluntarily creating and sharing memes means a great asset to a politician.”

First lady’s fan club

First lady Kim Keon-hee, who is not a politician but a political figure tied to the right wing in power, has a growing online fandom. One fan club on web portal Naver alone has over 94,000 members.

In the online community, talking points refuting criticisms of Kim are listed for people to see, along with posts instructing members to organize and work toward a common goal are easily found.

|

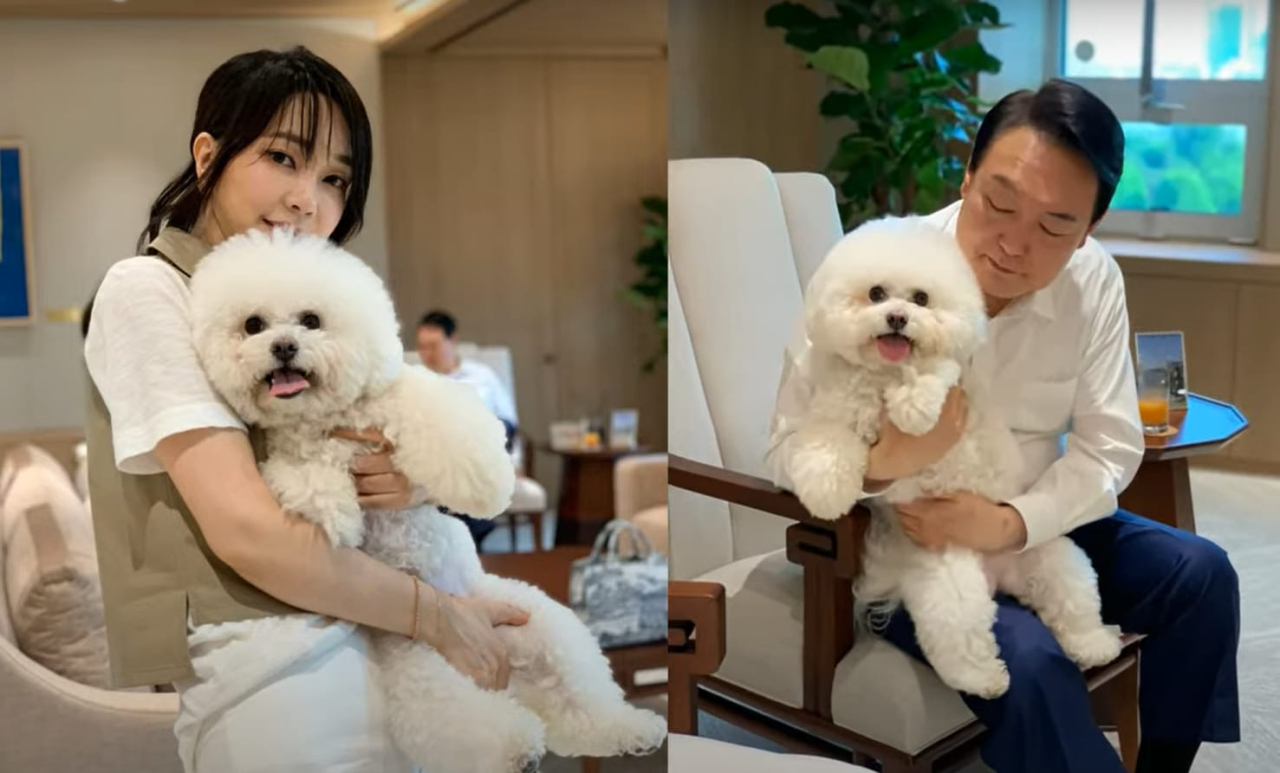

First lady Kim Keon-hee sits next to President Yoon Suk-yeol in the presidential office in a photo released by her personal fan club. (KunheeSarang/Yonhap) |

One pinned post encourages people to leave positive comments on a light-hearted story about Kim’s growing presence at public events as the first lady. Another post written by one member urges people to sign a petition against Seoul’s student rights ordinance, which has been introduced by liberal-minded educators.

Such coordinated moves are reminiscent of tactics deployed by some K-pop fandoms, often in hopes of amplifying positive media coverage of their favorite acts or drowning out negative comments.

While K-pop fans use hashtags, fixed phrases and memes to ensure more social media exposure for their favorite groups, political supporters use online spaces to seek to sway public opinion on the internet.

But the phrase “fandom culture” has also been used negatively in recent weeks -- a label to characterize one’s politics as not inclusive.

A recent photo of Kim and her husband, President Yoon Suk-yeol, taken in the presidential office and was uploaded through her personal fan club raised security concerns.

Rep. Lee Sang-min of the Democratic Party of Korea said fandoms amounted to “blind obedience” in a Facebook post on Sunday and called on his party to be revolutionized.

Though the label might be new, fandom politics has been around for a long time, said Kim.

“Politicians were idolized even more in the past. If we take it to extremes, you could argue that fandom politics has always been around, except that the phrase has been abused to disparage opponents in the last 10 years,” he said.

Democratic Party’s part

The first politician whose supporters were described as fans was former President Moon Jae-in.

Known as “Moonppa,” his avid supporters wield a strong presence on social media platforms, including Twitter, coming to his defense whenever he was criticized. Moon’s official Twitter account, the same account he used as president, also boasts 2 million followers.

In the paper titled “Dual characteristics of Moon Jae-in’s fandom,” professor Oh Hyun-chul at Chonbuk National University argues that Moon’s fandom is a typical example of the “new participation wave of political fandom” in South Korea’s political culture. The scholar cites leaving positive comments online, criticizing the media and creating merchandise as examples of fandom activities.

But Moon’s supporters have been criticized for being hostile toward those who do not share the same views as them and allegedly ganged up against critics in cyberspace.

Rep. Lee Jae-myung, a former presidential candidate for Moon’s liberal Democratic Party, has not been free from criticism over fandom politics either.

|

Flower wreaths near the main gate of the National Assembly sent by Rep. Lee Jae-myung’s loyal supporters on Tuesday celebrate the lawmaker’s return to politics. (Yonhap) |

The former Gyeonggi governor has developed his own fandom known as “gaeddal,” which literally means “dog daughters” and mainly consists of progressive-leaning young women voters. As Park Ji-hyun, an activist against digital sex crimes, joined his campaign and Lee went all-out to appeal to young women voters, the fandom began to grow.

While Lee’s avid supporters have proven to be a political asset for him, they have also faced criticism within the party. In an interview with MBC Radio on Wednesday, four-term lawmaker Rep. Hong Young-pyo claimed he has received “up to 2,000 text messages” from “gaeddal” after he blamed Lee for his party’s defeat in the local elections.

‘Solo stan’: When fandom loyalty trumps party loyalty“Solo stans,” or “akgae,” refer to fans whose loyalty only lies with one member of a group, even to the detriment of others. These fans feel that their favorite member has been treated unfairly or is too good to be in the group and would fare better alone. The concept is not alien to politics. During the 2016 US presidential election, some supporters of Sen. Bernie Sanders refused to endorse Hillary Clinton after she won the Democratic nomination. This section of his fan base was called “Bernie or Bust.”

In the 2022 South Korean presidential election, 1 in 4 voters who supported Moon Jae-in in the 2017 election voted for Yoon, a conservative candidate who is now president, according to exit polls by KBS.

As these voters switched party affiliations, surveys showed that some Democratic Party supporters who supported former Prime Minister Lee Nak-yon in the primary were hesitant to back Lee Jae-myung -- the party’s presidential candidate who lost to Yoon by a record-low margin of 0.7 percent.

As the infighting between factions of the Democratic Party continues following its defeat in the local elections, fandom politics could get in the way of party politics, said professor Yoon Jong-bin of International Affairs at Myongji University.

“If our politics is mature, winners and losers would be embraced even within the same party but that does not seem to be the case,” the professor said.

“It would be fine if it were a call for the party to be innovative. But for Lee Nak-yon supporters to just downright say ‘no’ to Lee Jae-myung seems to show that they have not healed the rift caused by an election,” Yoon Jong-bin said.

“It is fandom politics getting in the way of party politics.”

By Yim Hyun-su (

hyunsu@heraldcorp.com)