As jellyfish are appearing in Korea’s coastal waters in increasing numbers each year, the damage caused by the creatures is also on the rise.

With some species found in the coastal waters weighing as much as 200 kilograms, jellyfish can not only reduce fishermen’s catch but also tear fishing nets. In addition, jellyfish have blocked water intake pipes at power stations.

Damages sustained by the fisheries, power and other industries are estimated at over 300 billion won ($264 million) each year.

For the general public, the most worrisome aspect of jellyfish is that they produce toxins as part of their hunting and defense mechanisms. Jellyfish use structures known as nematocysts that contain toxins. When a jellyfish’s nematocyst is stimulated, pressure builds up within the structure while a barb pierces the skin of the victim, and the poison is introduced.

While most species found in Korea do not present significant danger to humans, some produce highly toxic poisons that can result in the death of a sting victim.

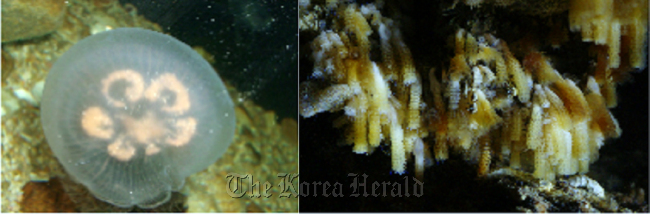

|

Fully grown moon jellyfish (left) and in polyp form. (Yonhap News) |

Of the 30 or so jellyfish species commonly found in Korea’s waters seven species are highly toxic including the Nomura’s Jellyfish, which is thought to have stung and killed a young girl.

This year saw the first death caused by a jellyfish in Korea when an eight-year old girl was stung at a beach on the west coast. Also, the number of people being treated for jellyfish stings in Busan has seen a 10-fold increase since 2008.

However, Yoon Won-duk of the National Fisheries Research and Development Institute’s jellyfish response team, says that jellyfish are much more than a nuisance that needs to be removed from the coastal waters.

“The government and the public regard jellyfish simply as harmful marine organisms but they should be viewed as being organisms with beneficial applications,” Yoon said. He added that removing them as they appear is not a viable answer as jellyfish are likely to continue appearing in large numbers in Korea’s coastal waters for several decades or more.

“We need to find a way to use jellyfish for beneficial ends without affecting marine ecosystems. That is the best answer for benefiting the country, fisheries industry and the public.”

There are examples of past research projects using jellyfish that gave results with long term applications.

Research in 1961 by a Japanese scientist to isolate the green fluorescent protein from a jellyfish species known as “crystal jelly” laid the groundwork for the protein to eventually be used as a marker in genetics experiments.

According to Yoon, another example of potentially beneficial use of jellyfish can be found in their toxins.

“Although it was seen only in experiments, jellyfish poison was shown to have anti-oxidation and blood pressure lowering effects. Also it was shown that jellyfish poison suppressed stomach cancer,” Yoon said. He added, however, that finding applications for jellyfish toxin is complicated by the fact that they consist of 150 or more different polypeptides, a short chain of amino acids, which is also the reason behind the difficulties of producing antidotes to jellyfish toxins.

“Related research was stopped in Korea about six years ago. But once the funding is revived, it is one of the first things that should be done, and fortunately the government is showing more interest in jellyfish issues.”

As for the reasons behind the rapid and continuous increase in the number of jellyfish, Yoon said that the exact cause has yet been identified.

“Jellyfish numbers are increasing rapidly in many areas across the world including the Gulf of Mexico, Alaska and the Mediterranean. However, even countries with 30 years of data have not been able to identify the causes of the increase,” said Yoon.

“We only have a number of suspected reasons, which are depletion of marine resources, pollution and increase in water temperature. For foreign species’ increase, we think that water temperature change is the mostly likely cause.”

While scientists work to pinpoint the cause of the rise in the number of jellyfish, the government is showing increasing interest addressing the problem, and appears to be looking at the issue from various angles.

One such angle is the recently announced plans to look into extracting collagen from jellyfish for commercial use.

However, as with research into jellyfish toxins, Yoon says that government funding is essential.

Saying that extracting collagen from jellyfish is easily achieved, Yoon said that the government needs to establish the necessary infrastructure such as a system for buying up jellyfish caught by fishermen.

“The most important thing is removing water (from jellyfish). Nomura’s and moon jellyfish are more than 96 percent water, and without efficient means for reducing the water content to about 20 percent, the costs (of using jellyfish-derived materials) would be too high.”

By Choi He-suk (

cheesuk@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Korea, don't repeat Hong Kong's mistakes on foreign caregivers'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050481_0.jpg)

![[KH Explains] Why Yoon golfing is so controversial](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050608_0.jpg)