In Korea’s turbulent path toward independence and nation building, there were foreign nationals who stood steadfastly by the Korean people, although their contributions have been largely overshadowed by those of Korean patriots. The Korea Herald, in partnership with the Independence Hall of Korea, is publishing a series of articles shedding light on these foreigners, their life and legacies here. This is the 11th installment. ― Ed.

|

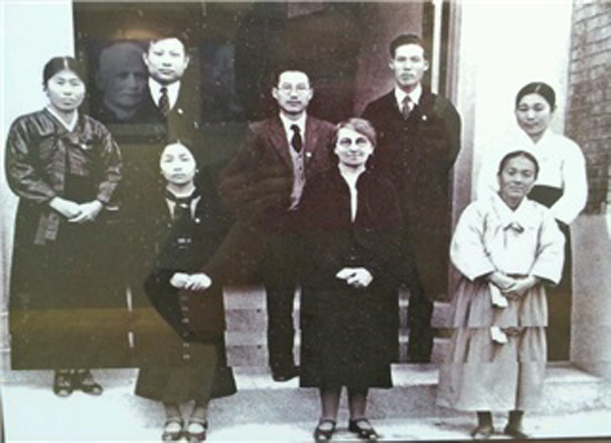

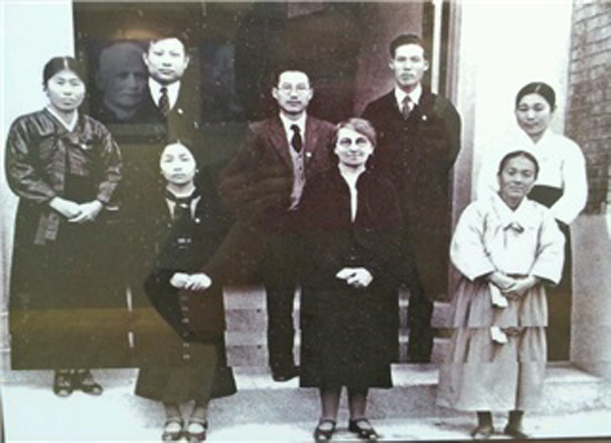

The missionaries and their families in the Busan Missionary Union in June 1937 |

What was in the foundation on which Korea was able to develop its current democracy and education? Although some nationalist Japanese say that Korea was able to develop as it is today thanks to Japan’s help during the colonial period, this is a preposterous claim based on a complete distortion of history. The foundation by which Korea recognized the need for today’s institutions and education systems was laid by the missionaries who came over to Korea and planted the seeds of national education and consciousness and the Koreans who responded to those missionaries’ efforts and exerted their own will.

Busan in the modern period was an important door to the Asian continent and the Pacific Ocean at the same time. Dadae, Busan, Yongdang, and Suyeong were the five representative port cities of Joseon Dynasty as well as critical geographical points of contact between Asia and the Pacific Ocean. Foreign missionaries frequently entered the country through these ports, and their influence spread through direct contact with Koreans.

With the wave of modernity rising after opening its ports, Joseon was at the boundary between the traditional and the modern. The strangers who sent shockwaves through the Koreans were the missionaries. Although they were active all over the country, they were charged with an important role also in Busan. The first organization to set base in the Busan-South Gyeongsang Province region was the U.S. Presbyterian Church, with the Australian missions leading the efforts afterward.

The first Australian missionary dispatched to Busan in October 1889, Joseph Henry Davies, worked proactively for Korean missions in recognition of their urgency. Traveling throughout the entire country, he established a plan for missionary activities. However, after a rigorous march in the vicious cold, he caught pneumonia and died, 183 days since arriving in the country.

|

Ilshin Girls' School teachers pose before the closure of the school in opposition to worshipping at Shinto shrines |

After Davies’ death, the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Union was established in Australia. On Oct. 12, 1891, Rev. James H. Mackay and his wife Sara, and members of the PWMU, Belle Menzies, Fawcett and Jean Parry, were dispatched to Busan.

Their passion continued with the purchase of two plots of land on a hillside in Choryangin in April 1893. There they began to provide opportunities to the marginalized women and children, instigating great changes with various philanthropic work.

Driving force of modern education

The first impressions and thoughts missionaries had about Busan were interesting. James Scarth Gale’s first impression was: “All Koreans wear white clothing, are taller than the Japanese and good looking, but carry smoking pipes with them. However, when the pipes are not in their mouths, they are strapped to the waist of their trousers or on their back.” He was a “Koreanized” missionary who was active for about 40 years until 1927. Seventy-eight Australian missionaries were active in the Busan-South Gyeongsang Province until they were forcibly evacuated in 1942 by the Japanese colonial authorities.

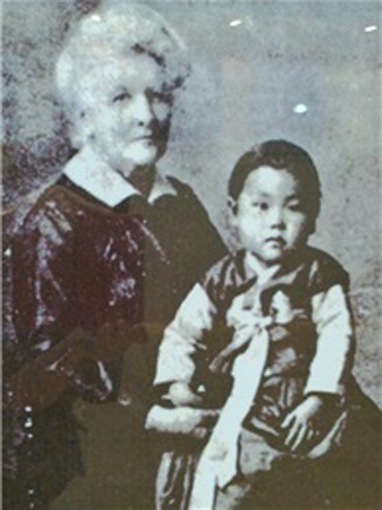

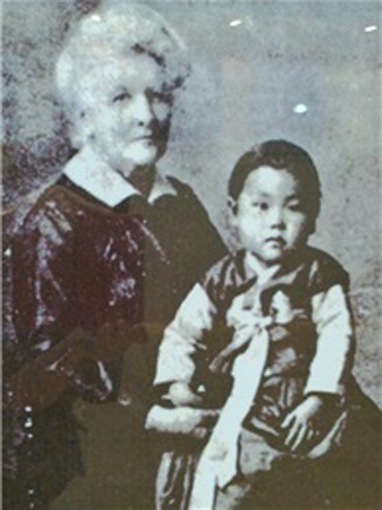

The unmarried Menzies, who arrived in Busan in October 1891, received the respect of the people in Busan until her retirement in Korea in 1924. She laid the embers for female education against the convention of that time, acting as the first principal of Busan County’s Ilsin Girls’ School (now Dongnae Girl’s Middle School). These missionaries not only proselytized to the locals, but worked as the driving force behind the region’s modern education and the change in popular consciousness.

Blue-eyed missionary

The Australian Missionary Union that occupied two plots of land in Busan County set the foundation for missionary activities with vigorous educational projects. In 1892, Menzies and Parry established Myoora Orphanage in a three-room thatched-roof house and raised three female orphans. Their dedication expanded to the operation of a day school that educated orphans and children. The name of the school, Ilsin, meaning “everyday new,” was the forerunner to Ilsin Girls’ School. Afterward, a three year-course elementary school was founded in 1895. This was the first modern female educational institute in the Busan-South Gyeongsang Province region, Ilsin Girls’ School.

Parry and Menzies led the change in the consciousness of children and women through Ilsin Girls’ School. The first principal, Menzies, was the paternal aunt of two-time Prime Minister of Australia Robert Gordon Menzies. She dedicated herself to the modernization of education, Christianity, gender equality, and democracy in the belief that “Wives and mothers need to be educated in order to develop the country.” Living for 33 years in Busan after her arrival in her 20s, she spread modern education faster than in any other region by acting as the godmother of Busan’s female education.

|

Principal Menzie and the girl she raised, Min Sin-bok |

Menzies’ steadfast belief was the source of energy for instilling proper beliefs in her female students. Moreover, education emphasizing Koreans’ self-esteem extended to patriotism. Notably, the Busan March First Movement was led by the students of Ilsin Girls’ School on the dawn of March 11, 1919. The teachers and students gathered in dormitory rooms in order to prepare for the March First Movement, bringing calico and bamboo and drawing taegukki, Korean national flags. On March 11 in Jwacheon-dong, taegukki fluttered in the air. Led by the principal and a female teacher, Ju Kyeong-ae, the female students held taegukki and loudly shouted “Long live Korean independence!” on the main road of Jwacheon-dong.

The movement’s leading students were Kim Sun-i, Pak Jeong-su, Kim Bong-ae, Kim Bok-seon, and I Myeong-si. Graduates such as Kim Ban-su (seventh class), Sim Sun-ui (seventh class), Kim Ung-su (eighth class), Kim Nan-chul (ninth class), Kim Sin-bok (ninth class), and Song Myeong-jin (10th class), and students Kim Sun-i, Pak Jeong-su, Kim Bong-ae, Kim Bok-seon, and I Myeong-si also led the Movement. Although they were all arrested and imprisoned, they were welcomed and encouraged by many Busan citizens when they were released.

In 1924, the Ilsin Girls’ School moved from Jwacheon-dong to Bukcheon-dong, Dongnae. On Jan. 6, 1926, the founder was the preacher J. N. Mackenzie and Miss Davies was the principal. With six faculty members and sixty students, Ilsin Girls’ school resettled with its school and dormitory fully furnished in new modern-style construction.

In 1938, the Japanese colonial authorities promulgated the third Joseon Educational Order, presenting three educational directives: “Clear Evidence of Embodying the State,” “Japan and Korea as One Entity,” and “Endurance Training,” changing the “Education of Subjects of the Japanese Empire” to “Education for Japanization of Koreans.”

The forced worship at Shinto shrines put many missionaries at a crossroads of having to choose between following the policy or shutting down the schools. The Australian Missionary Union conducted an on-site investigation to grasp the situation and concluded, “We refuse to worship the Shinto shrines as it violates the will of God and would rather retire from working in education.” Finally, on March 30, 1939, the Ilsin Girls’ School voluntarily shut down in resistance against the policies of the Japanese Governor General.

Love of humanity

Busan was the gateway into Joseon. To the missionaries, their impressions of Busan were their first impressions of Joseon. They spread modern civilization to Koreans while enthusiastically exerting themselves in many fields such as missionizing, education, and medicine, enlightening Koreans attached to the traditional ideas with new education and contributing to changes in the consciousness of marginalized children and women through education. After entering through Busan, the missionaries went to every region of the country, spreading advanced products of modern civilization and modern ideology as well as respect for humanity and equality.

The Australian missionaries active in the Busan-South Gyeongsang Province region numbered 78 until they were forcibly evacuated by the Japanese colonial authorities. Despite the poor environment, they were consistently active in missionizing. Seven died confronted with contagious disease and difficult environments. The missionaries were together with the Koreans at the scene of their oppression and suffering during the Japanese colonial period. Opposing the forced worship of Shinto shrines with the Koreans, they cannot be seen as strangers to us. They protected liberty and peace and realized the true universal values of humanity.

In 1942, the missionaries were forcibly deported by the Japanese.

By Sim Ok-joo, Director of the Korean Women Independence Movement Research Center