If batteries end up in landfills, it defeats the purpose of buying electric vehicles for the sake of the environment, which is why battery recycling is getting so much attention.

But establishing a circular economy for spent electric vehicle batteries is not an easy task and can’t be compared with doing so for plastic bottles. Due to their complex structures, disassembly can only be done manually, entailing high labor costs and serious safety risks.

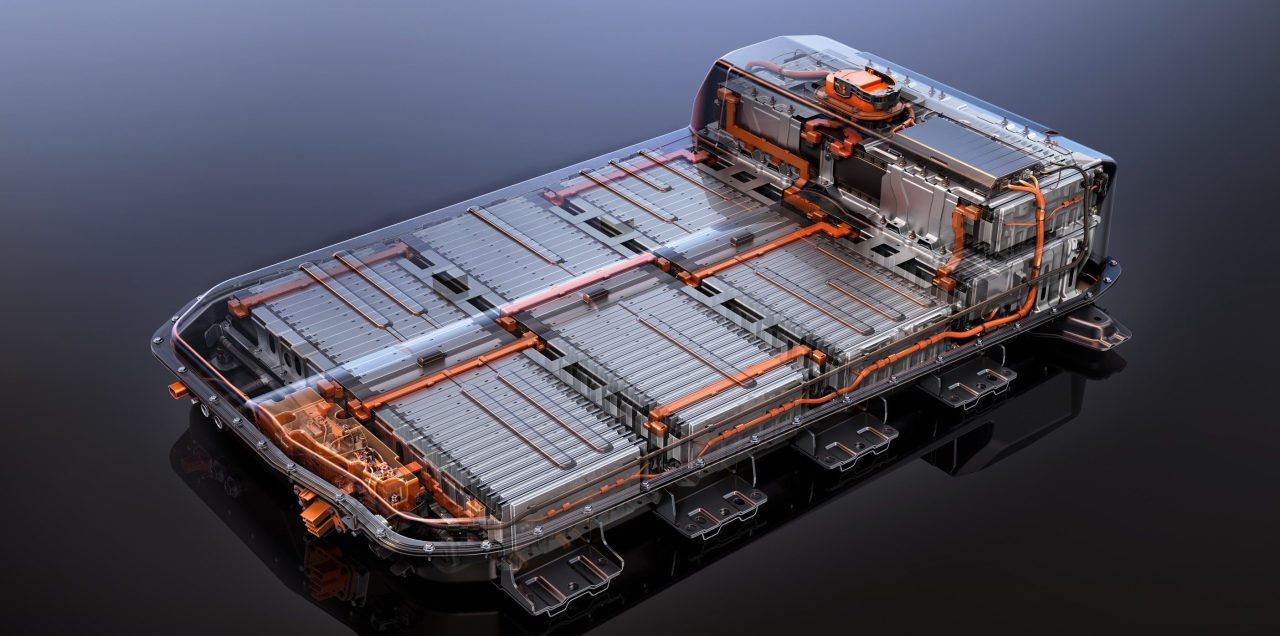

Inside an EV, battery parts fit together like Russian nesting dolls. Hundreds or thousands of cells make up a module, and a number of modules are assembled to make the battery pack.

“Modules and the cells inside are welded together. The process of detaching cells one by one manually is time-consuming and undermines profitability, which is why battery makers shun getting involved in the disassembly process,” said Jin Kyung-soo, an official at Earthtech, the South Korean firm that built the country’s first EV battery recycling center in March last year.

Located in Yeonggwang, South Jeolla Province, the 24 billion won facility can take apart up to 5,000 EVs and process 2,000 metric tons of dead batteries annually. The business model is to retrieve the precious metals, mainly cobalt, and sell them back to the market.

As to why the facility doesn’t automate the disassembly process with robots, Jin pointed out the lack of standardization: The design of each pack, module and cell is different. Different designs require different tools, making disassembly all the more complicated.

On top of differences in size and format, battery packs also contain sensors, circuitry and other electrical and electronics components that have to be disposed of.

“In the case of Japan, the industry is making efforts to use standardized modules for the post-treatment of batteries,” Jin said.

Responding to calls for the standardization of battery packs, modules and cells, Korean battery makers acknowledge the need but appear to have few incentives to push for it.

“Modules require customizations on their weight, location of connectors, amount of cells, capacity, power outage, among others. The idea of standardizing modules is equivalent to installing the same engine on all (gasoline) cars. The world can’t suddenly ditch straight-six engines and move on to straight-four engines, for example,” an LG Energy Solution official said.

Samsung SDI, which manufactures battery packs, believes designs will eventually be standardized, but says efforts must be made from both ends, especially from recyclers.

“When EV chargers first came out, they were all different, but now they’re standardized. The same will apply to battery packs. Then the battery recycling industry will take off,” a Samsung SDI official said.

“Recyclers have to make efforts to accommodate any type of battery pack through automation. They can analyze the platforms of the top five automakers, for example, and learn about the right coverage of the automated equipment they need.”

Experts say recyclability could eventually become a source of competitive advantage for battery manufacturers. Currently it is not a primary concern due to price competition and pressure to meet a range of requirements concerning high energy and power density, safety and product lifetime.

Kim Pil-su, a professor of automotive engineering at Daelim University, stressed that lack of standardization can pose grave safety risks to disassembly workers.

“Battery packs have to be fully discharged before they are disassembled. If this isn’t done properly, workers will be electrocuted,” Kim said.

Since battery packs are heavy and have high voltage, specialized tools and qualified employees are needed. If residual energy isn’t drained to a safe level, short circuiting or self-ignition can happen during dismantling.

Another problem is that even if disassembly workers manage to safely dismantle spent battery cells, recyclers don’t know what to do with them due to lack of information and technology, the professor said.

Every bag of chips has a label on the back that shows detailed information about the product -- calories, carbs, fat, protein and so on. But battery packs, modules and cells provide minimal information on their labels, such as their capacity and power outage, and do not mention their specific composition.

This unfriendly labeling makes identification, sorting and grouping of battery cells nearly impossible. As recyclers don’t know what kinds of cells they are dealing with, they cannot extract precious metals in their purest forms.

The labels on the battery products of LG Energy Solution, Samsung SDI and SK Innovation only provide basic information or no information at all.

To address the labeling issue, the Society of Automobile Engineers recently recommended a standardized labeling system, and the Chinese authorities are also considering mandating labeling of EV batteries.

Also, recyclers can’t evaluate the true worth of spent batteries because there are no tools to do so.

“Right now, there is no proper equipment in the industry to precisely measure the state of charge, a ratio of a battery cell’s current capacity to its original capacity. Because of this, recyclers can’t decide which used-up battery cells are eligible to be reused for energy storage systems, for instance. Also, it’s difficult to determine the right price of secondhand EVs because no one knows the exact condition of old batteries,” professor Kim said.

In January, Hyundai Motor Group and OCI installed two ESSs -- one with new batteries and the other with spent ones -- at a solar farm to figure out how well old batteries performed inside an ESS.

Above all, experts warn that as battery technology continuously evolves, by the time a 15-year-old spent battery arrives at a recycling center, it may be of such little economic value that it may not even be worth the hassle of recycling.

For recyclers, cobalt, the most expensive metal inside dead batteries, is their primary target.

But battery manufacturers are gradually shifting away from cobalt due to its high costs and issues regarding the mining process, in particular the negative impact on the environment and on miners’ health.

In June, Samsung SDI unveiled a cylindrical nickel-cobalt-aluminum battery whose cathodes contain 91 percent nickel, as compared with the previous 89 percent model. SK Innovation is also working to increase the ratio of nickel inside the cathodes of its nickel-cobalt-manganese batteries from the current 90 percent to 95 percent within three years. With their higher nickel content, the new batteries would have less cobalt, although the firms do not disclose exact data.

By Kim Byung-wook (

kbw@heraldcorp.com)