SEJONG -- Household debt in South Korea has hogged the limelight in recent decades.

The nation’s collective household debt has continued to rise in the wake of active credit card issuance, mortgage loans, student loans for college tuition and loans taken by the self-employed.

Apart from first-tier commercial banks, secondary lenders -- such as capital services firms, credit card issuers and savings banks -- have engaged in cutthroat competition for household lending.

Registered private moneylenders, especially with capital from Japan have also expanded their presence. They are classified as a third-tier lender by the Financial Supervisory Service.

The nation suffered its “credit card fiasco” in 2003, with a growing number of defaulters due to the reckless doling out of credit cards irrespective of credit standings.

Still a large portion of credit card holders are engaging in “juggling” their debt, under which they pay existing credit card debt with other cards and resort to cash advance services or credit card loans, both of which levy annual interest rates of about 20 percent.

The more serious issue is apartment mortgages.

|

A commercial bank teller deals with a customer for the mortgage loan process. (Yonhap) |

The previous Park Geun-hye administration drastically eased regulations on mortgages in a bid to boost the economy by invigorating the real estate sector. The key government advice from 2014 to 2016 was “Buy homes by taking out loans!” amid the active coordination by all related authorities.

More households rushed to book apartments on the back of easier lending terms for mortgages. In addition, the government took lukewarm stance toward those trading two or more apartment units seeking huge capital gains.

As a result, commercial banks are de facto owning a large percentage of apartment units now, as many households do not have the capacity to pay the principle and interest on mortgages.

According to a report from the Bank of Korea, the ratio of nonfinancial assets, including lands and buildings, held by Korean households came to 75.4 percent, far higher than in Japan with 43.3 percent and the US with 34.8 percent.

The heavily indebted situation of households is also hampering private consumption and, eventually impact economic growth.

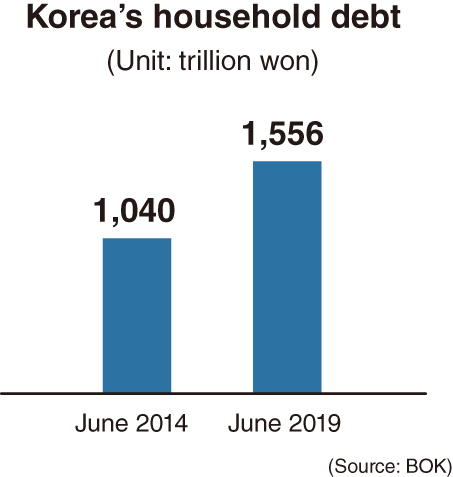

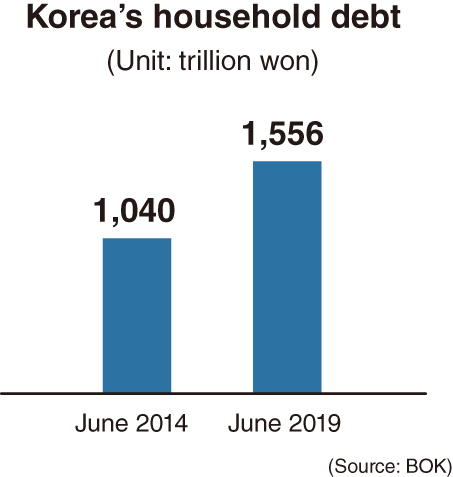

Outstanding loans to the household sector reached a record of 1.556 quadrillion won (1,556 trillion won or $1.29 trillion), as of June 2019, according to the BOK. Though the growth pace has slowed, it posted an increase of 4.3 percent on-year.

Furthermore, compared to five years ago in June 2014, when the outstanding household loans stood at 1,040 trillion won, it recorded a 49.6 percent surge.

|

(Graphic by Kim Sun-young/The Korea Herald) |

The ratio of household debt to disposal income climbed 2.4 percentage points over the one-year period to reach 159.1 percent as of June this year. This means their debt growth rate is still outstripping their income.

According to the Institute for International Finance, South Korea saw the ratio of household debt-to-gross domestic product come to 97.9 percent at the end of 2018. That is much higher than the global average of 59.6 percent.

While household debt-to-GDP inched up 0.2 percentage point globally from 2017 to 2018, the figure for Korea rose 3.1 percentage points. It was 94.8 percent at the end of 2017.

A professor in Seoul was quoted by a news outlet as saying that the nation should be alert to “possible insolvency of loans amid the economic slowdown, or to the opposite direction, any tighter monetary policies for rate hikes in the future (from an improvment in economic indices). The scenario of mounting bad loans could cause financial firms’ insolvency and a financial crisis.”

The debt per household on average came to 75.31 million won as of 2018, according to Statistics Korea.

Since August 2014, the BOK’s benchmark interest rate has stayed under 2.5 percent per annum, which sharply fanned mortgages. It is set at 1.5 percent now.

By Kim Yon-se (

kys@heraldcorp.com)