SEJONG -- Compared with past governments, the Moon Jae-in administration has been actively increasing public expenditure to benefit jobless people in their 20s and early 30s.

However, many have cast doubt on the efficacy of its strategy of pouring dozens of trillions of won in taxpayer money into job creation over the past two years since May 2017.

This year, the incumbent government is struggling to prevent the economic growth rate from falling sharply by proposing a supplementary budget bill, drawn up by the Finance Ministry.

|

(Graphic by Heo Tae-seong/The Korea Herald) |

The move has prompted speculation among analysts and online commenters that the government is desperate to prevent gross domestic product growth from remaining below the 2 percent mark this year.

While the free flow of state funds may benefit some economic activities, especially in the public sector, the continual injections of taxpayers’ money have many observers worried about fiscal soundness.

For one thing, the Ministry of Economy and Finance is reportedly considering issuing state bonds for the purpose of reinvigorating the economy. This will inevitably cause a surge in national debt and increase the tax burden, which will ultimately be borne by ordinary households.

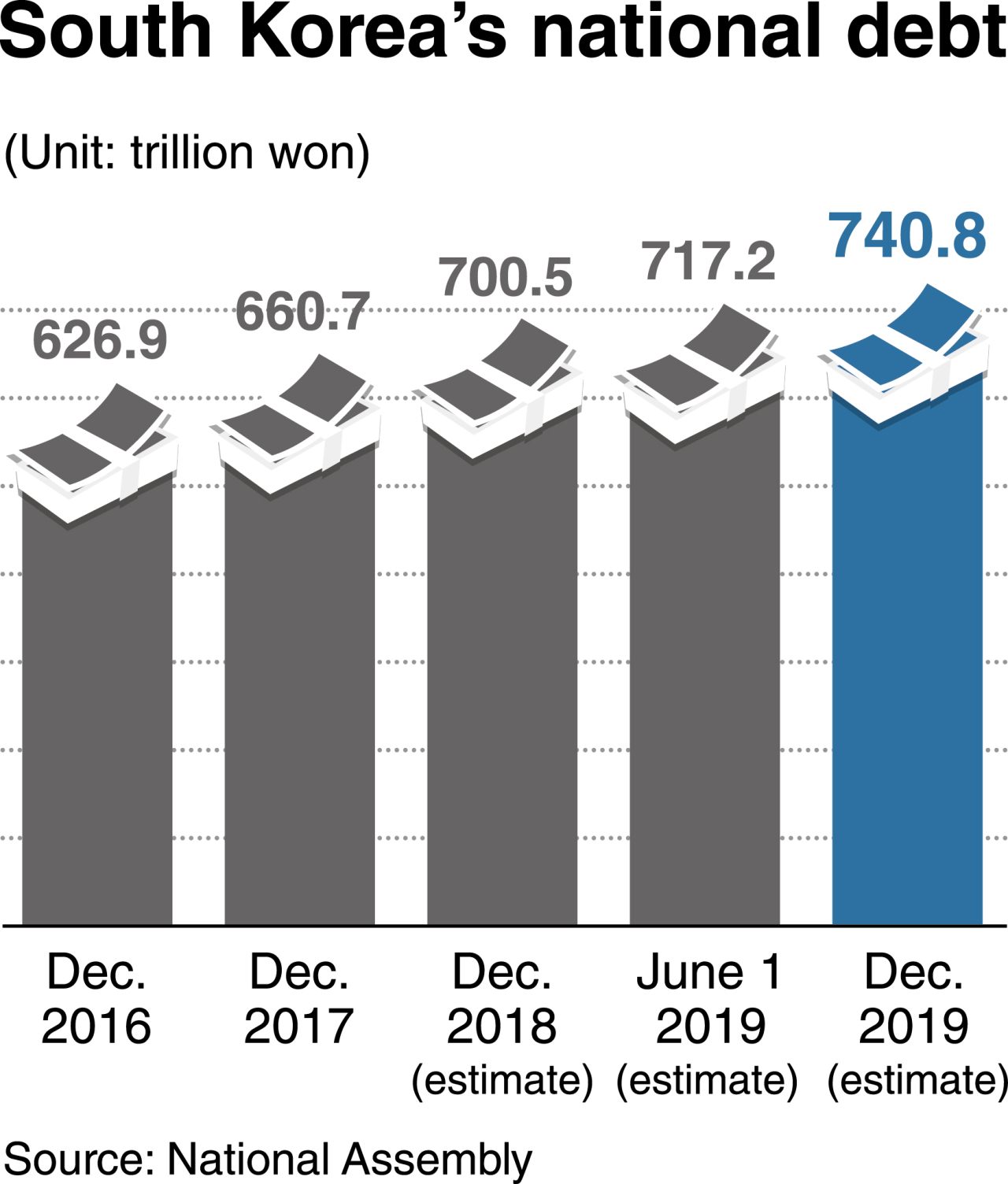

Amid this news, the ratio of public debt to GDP -- an indicator of fiscal soundness, reflecting all debt held by the central and local governments -- is projected to break through the 40 percent mark in 2019 or 2020 for the first time in history, according to the Finance Ministry’s report to the National Assembly on its midterm fiscal policy.

More recently, in a meeting with lawmakers from the ruling Democratic Party, Finance Minister Hong Nam-ki reportedly expressed the ministry’s intentions of pursuing even stronger fiscal expansion in the coming years.

A Democratic Party lawmaker was quoted by a news provider as saying that the ministry was backing away from its earlier plans to limit the national debt-to-GDP ratio to about 41.6 percent for the 2018-2022 period, and was now prepared to tolerate a ratio that approached 45 percent by 2022.

This hints that the Moon administration might possibly continue to use taxpayers’ money too freely and to issue bonds just as freely until the president’s term ends in May 2022.

The sovereign debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to have hovered around 38-39 percent in 2018.

A debt-to-GDP ratio of 45 percent would see South Korea’s debt reach 1,160 trillion won ($976 billion) within three years.

According to the National Assembly Budget Office, the national debt was estimated to be 717.2 trillion won as of June 1.

This marked an 8.5 percent (or 56.5 trillion won) increase in 17 months, as compared with 660.7 trillion won at the end of 2017. Estimates for the end of 2018 range between 680 trillion and 700.5 trillion won.

Parliamentary estimates also suggest that per capita national debt has reached 13.84 million won for a population of 51.81 million this year, having exceeded the 13 million won mark for the first time in February 2018.

A macro-finance research analyst in Seoul compared the recent figure with the 10.52 million in per capita sovereign debt posted in 2014, saying, “The burden of national debt per citizen has increased more than 30 percent over the past five years.”

He also warned of the risk of snowballing liability, citing the eurozone crisis in the early 2010s.

|

The Government Complex Sejong in Eojin-dong, Sejong (Yonhap) |

A great number of business insiders and online commenters have continued to point out that the present difficulty in the overall economy lies in the Moon administration’s “income-led” growth policy.

The policy imposed a tough burden on microbusinesses owned by self-employed professionals in the wake of drastic hikes in the minimum wage for 2018 and 2019. This led to fewer job opportunities for younger workers because business owners hesitated to hire them.

Despite the liberal use of taxpayers’ money to promote job creation, unemployment rates both for young and middle-aged workers are rising.

As a result, the government is obliged to pay out more of its rapidly increasing unemployment benefits, which are set in accordance with the higher minimum wages -- 8,350 won per hour and 1.74 million won per month as of 2019.

The corresponding figures were 6,470 won and 1.35 million won two years ago, when Moon took office.

By Kim Yon-se (

kys@heraldcorp.com)