After Fred Wallace was laid off from a high-paying job in 2011, the 56-year-old knew the odds of landing a comparable position were slim.

He polished his LinkedIn profile and networked like crazy. But his yearlong job search yielded only a handful of interviews and no offers.

So he shifted gears, embarking on an “encore” career by working part time at a child and family services organization in San Bernardino, California.

Wallace is among millions of older Americans launching professional second acts revolving around some form of public service. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, encore careers have caught on among baby boomers, some of whom recoil at the notion of conventional retirement ― or aren’t financially prepared.

Wallace uses the marketing skills he honed during 28 years at HBO to raise funds for a program helping young people smooth the transition out of foster care. It’s high-level work that brings personal fulfillment and a paycheck ― albeit a significantly smaller one.

|

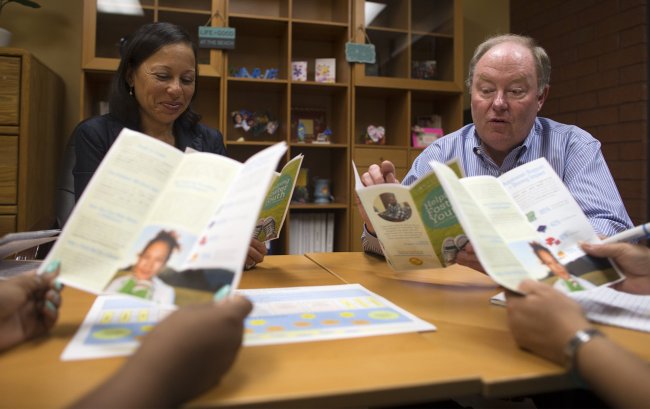

Jamie McCall, a district director for nonprofit organization Aspiranet, looks over a new brochure in San Bernardino, California, with Fred Wallace, an Encore.org fellow and former HBO employee brought in to the nonprofit to put his marketing skills to use. (Los Angeles Times/MCT) |

“It’s terrific to know you can help an organization be better at what they do, you can give back, and you can earn a modest stipend,” Wallace said.

Roughly 9 million Americans ages 44 to 70, or 9 percent of the 100 million people in that age range, work in encore jobs, according to a 2011 survey by Encore.org, a nonprofit organization, and the MetLife foundation. An additional 31 million would like to.

“People are going to live longer, and people of modest means are going to work much longer,” said Marc Freedman, the group’s founder. “How do we make that something people genuinely look forward to, and that could be important to society?”

The share of older Americans in the workforce has risen sharply since the mid-1990s, and polls show millions of people plan to work in years that once were classified as retirement.

Among those 55 and older, 40 percent have a job or are looking for one, according to the Labor Department. That’s hovering around the highest level since the early 1960s.

A survey last month by Merrill Lynch and research firm Age Wave found that 72 percent of people 50 and older plan to work in their “retirement” years.

“In the near future it will become increasingly unusual for retirees not to work,” the report said.

Many jobs in encore fields such as education and social services are relatively low-paying. That limits their viability for people with pressing financial needs, such as insufficient retirement savings or children’s college bills.

Wallace was accepted into an Encore.org fellowship program that places experienced professionals, often moving from the corporate world, into one-year, part-time internships with social-service organizations.

Wallace had a big 401(k), a pension from HBO and a generous severance package. Without those, he said, he wouldn’t have taken the lower-paying job.

“The fact that I’ve been able to save up money allows me the flexibility to work in the nonprofit world at a fraction of what I used to,” he said. “It’s something I can afford to do.”

Leslye Louie, the national director of the fellowship program, said many people who want to can land higher-paying, full-time jobs at the end of their internships.

Advocates say the encore dynamic is an initial step toward solving a critical social problem ― how to change perceptions about a steadily aging population.

“We have not created natural pathways for people to transition into new jobs that enable them to do something meaningful that takes advantage of their skills and enables them to earn a living,” said Paul Irving, president of the Milken Institute and a board member of Encore.org. “That’s clearly something we have to focus on as a society, and it is a challenge for many, many people.”

Despite the moderate pay, encore workers say they get a lot from their jobs.

Wallace, who lives in Playa del Rey, California, wanted no part of mundane or perfunctory volunteer work.

“You go to the food bank and put cereals into crates and you think, ‘OK, this is not really using your mind,’” Wallace said.

He was brought in by Aspiranet, a South San Francisco nonprofit, to develop a fundraising effort for a program that helps children who have grown up in foster homes transition to adulthood. He created a donor database and software before moving to a bigger role helping the organization develop broader strategy.

By Walter Hamilton

(Los Angeles Times)

(MCT Information Services)