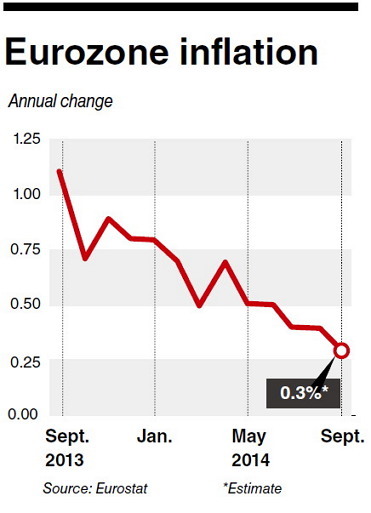

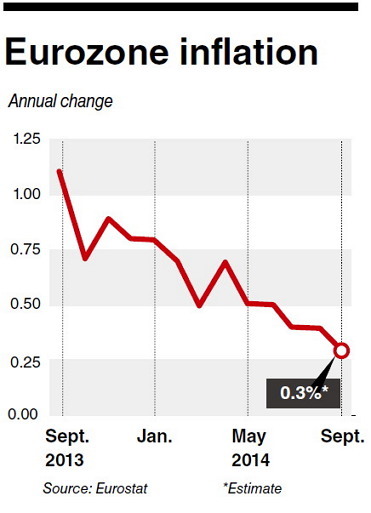

LONDON (AP) ― Inflation across the 18 euro countries dipped further toward zero in September, piling pressure on the European Central Bank to pull the trigger on its biggest stimulus weapon ― a large-scale program to create new money.

Expectations that the bank will back such a program ― similar to the one pursued by the U.S. Federal Reserve ― mounted Tuesday after official figures showed consumer prices in the eurozone rose only 0.3 percent in the 12 months to September.

The decline from the previous month’s 0.4 percent annual rate leaves inflation at its lowest since October 2009 and way below the ECB’s target of just under 2 percent.

Though the fall was largely due to a big 2.4 percent drop in energy prices and was widely anticipated in financial markets, a closer look shows a worrying underlying trend ― the core inflation rate, which excludes energy, tobacco, alcohol and food, fell to 0.7 percent from 0.9 percent.

“This is a serious blow to those still arguing that the weakness of inflation will be temporary,” said Jennifer McKeown, senior European economist at Capital Economics.

Traders think it’s now more likely that the ECB will back large-scale purchases of government bonds with newly created money ― called quantitative easing, or QE ― though not at this Thursday’s meeting. For now, it is likely to want to see whether other stimulus measures it unveiled in June and in September have an impact.

Following the inflation figures’ publication, the euro fell as low as $1.2571, the first time it’s been below $1.26 since the summer of 2012, when ECB President Mario Draghi said the bank would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. By late afternoon, it was down 0.5 percent at $1.2625.

Because QE would increase the amount of euros in the economy, diluting their value, expectations of such a program from the ECB have weighed on the currency. It’s down 9 percent against the dollar since May and its further drop on Tuesday suggests traders are preparing for the possibility of QE in coming months.

Obstacles remain, however.

Some countries, particularly Germany, Europe’s powerhouse economy, are worried that QE would amount to ECB financing for governments. Draghi has also been resisting calls for QE by insisting governments should speed up reforms to make their economies grow faster.

“I believe he will succumb to this pressure eventually, though perhaps not as soon as Thursday’s policy announcement,” said Ben Brettell, senior economist at stockbrokers Hargreaves Lansdown. “Stiff opposition from Germany will need to be overcome.”

The key will be whether economic indicators improve in coming months. If they do not, Draghi has said the ECB is ready to do more to help the economy.

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)