WASHINGTON (AP) -- Scientists have cracked the genetic code of the Black Death, one of history's worst plagues, and found that its modern day bacterial descendants haven't changed much over 600 years.

Luckily, we have.

The evolution of society and medicine _ and our own bodies _ has far outpaced the evolution of that deadly bacterium, scientists said.

The 14th century bug Yersinia pestis is nearly identical to the modern day version of the same germ. There are only a few dozen changes among the more than 4 million building blocks of DNA, according to a study published online Wednesday in the journal Nature.

What that shows is that the Black Death, or plague, was deadly for reasons beyond its DNA, study authors said. It had to do with the circumstances of the world back then.

|

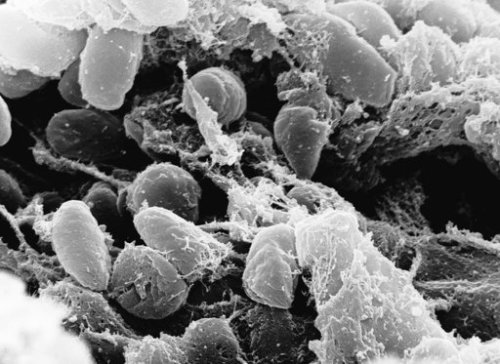

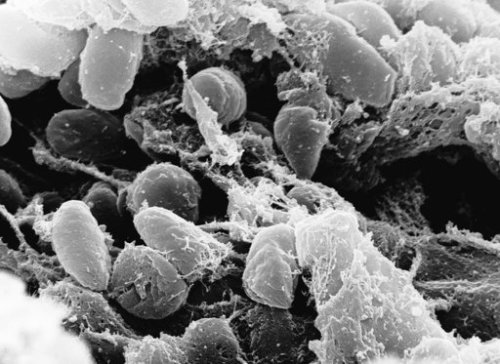

Undated handout image provided by Rocky Mountain Laboratories showing an electron micrograph depicting a mass of Yersinia pestis bacteria (the cause of bubonic plague). (AP-Yonhap News) |

In its day, the disease killed between 30 million and 50 million people _ about 1 of every 3 Europeans. It came at the worst possible time _ when the climate was suddenly getting colder, the world was in the midst of a long war and horrible famine, and people were moving into closer quarters where the disease could infect them and spread easily, scientists say. And it was likely the first time this particular disease had struck humans, attacking people without any innate protection.

``It was literally like the four horseman of the apocalypse that rained on Europe,'' said study lead author Johannes Krause of the University of Tubingen in Germany. ``People literally thought it was the end of the world.''

In devastating the population, it changed the human immune system, basically wiping out people who couldn't deal with the disease and leaving the stronger to survive, said study co-author Hendrik Poinar of McMaster University in Ontario.

But simple antibiotics today, such as tetracycline, can beat the plague bacteria, which doesn't seem to have properties that enable other germs to become drug resistant, Poinar said. Plus, changes in medical treatment of the sick, coupled with improved sanitation and economics, put humanity in a far better position. And there's an immune system protection we mostly have now, Poinar said.

``I think we're in a good state,'' Poinar said. ``The reason we do so well is that conditions are so different.''

People still get the disease, usually from fleas from rodents or other animals, but not that often. There are around 2,000 cases a year in the world, mostly in rural areas, with a handful of them popping up in remote parts of the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To get the original Black Death DNA, scientists played dentist to dozens of skeletons.

During the epidemic in the 14th century, about 2,500 London area victims of the disease were buried in a special cemetery near the Tower of London. It was excavated in the mid-1980s with 600 individual skeletons moved to the Museum of London, said study co-author Kirsten Bos, also of McMaster University. She then removed 40 of those teeth, drilled into the pulp inside the teeth and got ``this dark black powdery type material'' which likely was dried blood that included DNA from the bacteria.

And when she was done, Bos returned the teeth, minus a little DNA, to the skeletons at the museum.

When the same scientists first tried mapping the bacteria's genetic makeup, it appeared to be a distinctly different germ than what is around currently. But part of that was a reflection of working with 660-year-old DNA and newer, more refined techniques revealed less difference between the early day and modern Y. pestis bacteria than between a mother and daughter, Krause said.

That's a surprising result, but the work was well done and makes sense, said Julian Parkhill, a disease genome expert at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Britain. Parkhill was not involved in the research but has studied the bacteria.

``Getting an effectively complete genome sequence of a bacterium that lived nearly 700 years ago is incredibly exciting,'' Parkhill said.

<한글기사>

흑사병균은 모든 현대 병균의 조상

인류 역사상 가장 참혹했던 전염병 가운데 하나인 흑사병의 병 원균 게놈 지도가 처음으로 완전히 해독됐다고 사이언스 데일리와 BBC뉴스가 12일 보도했다.

독일과 캐나다 등 국제 연구진은 런던의 `페스트 공동묘지'에서 발견된 중세인 의 치아에서 채취한 세균의 DNA를 분석한 결과 이것이 무해한 세균의 새로운 변종인 동시에 모든 현대 전염병균의 조상으로 드러났다고 네이처지에 발표했다.

연구 결과 14세기 유럽을 휩쓸어 절정기인 1347~1351년 사이에 5천만명을 죽음 으로 내몬 흑사병은 인류가 처음 겪은 흑사병 창궐 사례라는 사실도 밝혀졌다.

연구진은 벼룩을 통해 유례없는 재앙을 가져온 흑사병 병원균인 `예르시니아 페 스티스'(Yersinia pestis)의 유전자 암호를 해독할 수 있었으며 그 결과 사람에게 감염될 수 있는 모든 종류의 병원균의 공동조상과 매우 가까운 것으로 드러났다고 밝혔다.

연구진은 "예르시니아 페스티스는 오늘날 존재하는 모든 병균의 할머니"라고 지 적했다.

이전까지 학자들은 흑사병이 고대 그리스와 로마 시대로 거슬러 올라가는 전염 병일 것으로 추측해 왔다.

그러나 이번 연구 결과 예르시니아 페스티스의 기원은 12~13세기로 드러났다.

따라서 6세기에 비잔틴 제국을 휩쓸면서 1억명의 목숨을 앗아간 유스티아누스 역병 은 중세 흑사병과 같은 병원균으로는 일어나지 않는 것으로 밝혀졌다.

연구진은 "유스티아누스 역병은 지금은 완전히 멸종한 페스트균 변종에 의해 일 어나 병원균의 후손이 남아있지 않거나 아직 전혀 알려지지 않은 다른 병원균에 의 해 일어난 것으로 보인다"고 말했다.

중세 흑사병 병원균은 아직도 후손이 남아 있어 연간 2천명이 이로 인해 죽지만 14세기에 비하면 위험이 매우 낮다고 할 수 있다.

연구진은 "흑사병 창궐 후 660년이 지났어도 병원균의 게놈에는 변화가 거의 없 었다"고 밝히고 그러나 이처럼 미미한 변화라도 병원균의 치명성에 영향을 미쳤을 수도 있고 그 반대일 수도 있었을 것이라고 지적했다.

연구진은 중세 흑사병이 그토록 맹위를 떨친 것은 병원균 자체의 맹독성, 흑사 병균과 함께 유행한 다른 병원균, 한랭화로 접어든 기후 등 다양한 요인의 영향 때 문으로 보인다고 말했다. (연합뉴스)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)