Taking the steep, narrow staircase to meet architect Seung Hyo-sang, or Seung H-Sang as his business card says, one almost fears for one’s life, tottering down the steps in heels with one hand against the wall for support in the semidarkness.

Upon reaching the floor, there is a sigh of relief and a sense of salvation as one follows the sound of choral music to Seung’s office. It is a few days before Christmas, and there is something of a sacred quality to the space, crammed with bookcases and a large desk with all sorts of things strewn over it. There is a sense of order to this apparent chaos -- three Montblanc ink bottles lined up neatly side by side, with the iconic bottle caps facing the edge of the desk.

|

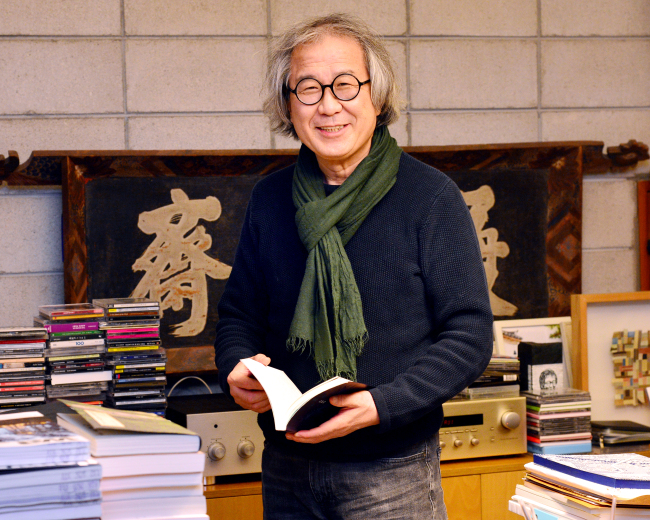

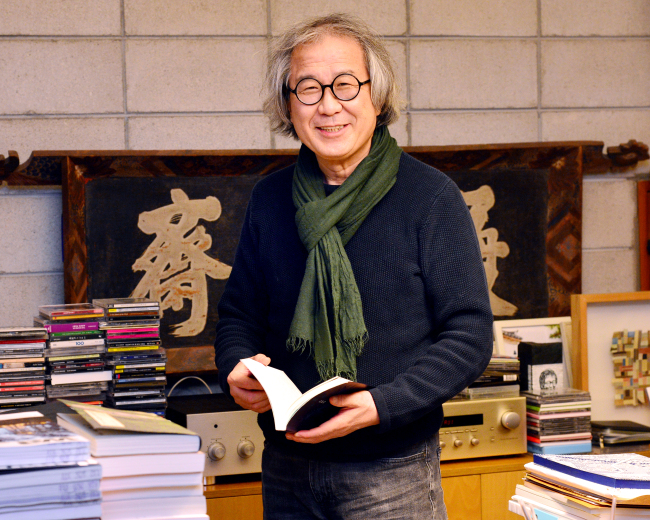

Architect Seung Hyo-sang poses at his office in Dongseung-dong, Seoul, on Dec. 20, 2018. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

|

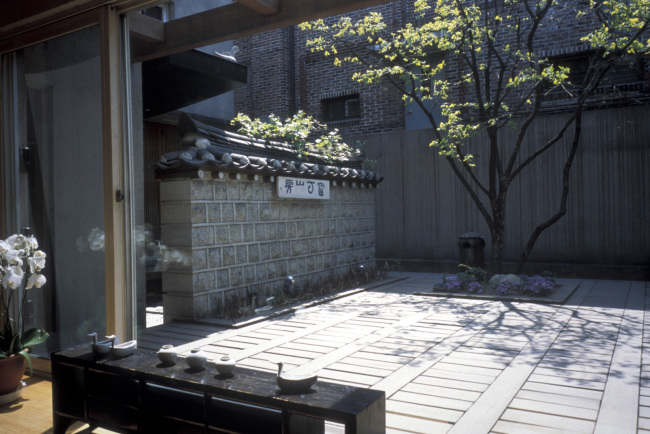

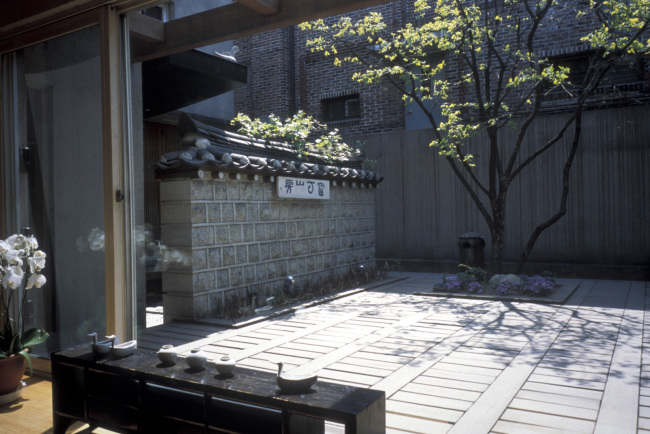

Architect Seung Hyo-sang's office in Dongseung-dong, Seoul, on Dec. 20, 2018. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

Then the sword. A real sword in a sheath that is casually laid across an armchair. “That is used for geomdo,” Seung explains.

He and his staff practice geomdo, a Korean martial art derived from Japanese kendo, for an hour starting at 7 a.m., Mondays and Wednesdays, in the basement.

“It is mandatory,” he says with a chuckle. Has anyone declined to participate or turned down an offer to join the firm because of this requirement? No one so far, he says, sounding confident that no one ever will.

Seated in front of his desk with hundreds of music CDs and a sound system behind him against the wall, he explains the music. “Something for Christmas,” he says, explaining how all the rooms in the building have speakers that play his choice of music for the day. The music is necessary because there are no doors in the building. Does anyone object to the house DJ’s choices? “Sometimes I find that my staff have unplugged the speakers,” he says with a laugh.

Seung, who likens architects to gods -- after all, they mold how people live within and around the spaces they create -- is obviously the master of his space and firm, named Iroje. Translated as “house of stepping on dew drops,” a phrase from classical Chinese literature, the name was taken from a 200-year-old signboard given to him by Yoo Hong-jun, a prominent art historian, for designing his house.

A box of CDs titled “Sacred Music” stands out among the CDs. One can’t be certain that Seung’s music has anything to do with his projects, but many of his works are related to religion or spirituality. His latest project, a facility for an arboretum in Daegu with a 500- to 600-year-old quince tree, is built for meditation purposes. “It is a small facility but it allows for spiritual reflection,” he says.

|

Myungrye Sacred Hill in Miryang, South Gyeongsang Province (Iroje) |

Then there are the churches and holy sites, such as the Myungrye Sacred Hill in Miryang, South Gyeongsang Province, which commemorates a Korean Catholic martyr.

Commenting on the number of churches and religious facilities he has built -- he has built about 10 churches, including his first-ever building project, which was a cathedral -- compared to commercial projects, which are fewer, he says, “I don’t get many commissions for commercial facilities. This is probably because of my personality. Monetary profits alone don’t move me.”

|

Daejeon University Hyehwa Residential College by Seung Hyo-sang (Iroje) |

Most of his projects in Korea are commemorative halls, religious facilities and cultural facilities, although in China, where the building system is very different, he has been commissioned to design apartment buildings and commercial buildings.

A church elder, Seung is not happy with many of today’s new megachurch buildings. “Church buildings are losing their godliness, they are too commercial,” he says, adding that the essence of Christianity is not about elaborate buildings.

Chief of architectural policy

Seung was appointed the chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architectural Policy in 2018. From 2014 to 2016, he served as the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s first city architect, overseeing many of the capital’s public projects.

As the head of the architectural policy commission, his primary focus is abolishing the building permit system, Seung says. “It often leads to corruption, and no other advanced country has this system,” he says. The abolition of the building permit system would bring about a change in the entire system, including the education of architects, according to Seung. He predicted many changes will begin with public projects. He notes that the changes he instituted as Seoul’s city architect has led to greater transparency and encouraged many young architects.

“If buildings are important, then the lives lived in those buildings are also important,” he says, adding that it is possible to make a life healthier through architecture.

|

Sujoldang, art historian Yoo Hong-jun‘s residence, designed by Seung Hyo-sang (Iroje) |

Indeed, Seung has often expounded on the authenticity of buildings. Criticizing the National Assembly building, for example, for its columns and rotunda that do not serve any function but were added on as last-minute thoughts to give the building “authority,” he has argued for the building to be demolished. “People in inauthentic buildings become inauthentic,” he said in a recent lecture.

Seung also vehemently opposes landmarks, which rulers often resort to in an attempt to burnish their legacy. “The landscape is the landmark,” he says, pointing out that artificial landmarks have nothing to do with daily lives.

Many people quite wrongly disdain spaces for day-to-day living, Seung says, citing the example of public facilities. “Life will be happier when they (public facilities) are improved,” he says, adding that work on changing the law on public buildings will start soon.

What is a happy city in his view? “Everyone is given the same conditions, the sunrise, the sunset. Happiness is about being moved by one’s world. Architecture enables this,” he says.

As the chief architect of the country, Seung intends to voice his concerns about new satellite cities. “I plan to make a serious recommendation against building them like they have so far,” he says. In his view, buildings must suit the land upon which they will be built. “Otherwise we have cities that have no relationship with the land,” he warns. “We need to use the elements of the existing topography.”

He is also anxious about the development of North Korea. “One of my concerns is the South’s developers who want to march on to the North,” he says. But he is even more worried about Chinese capital, warning that Chinese developers could be even more reckless.

He noted that East Berlin, though it was run-down, functioned well as public space. However, things changed after unification. “When I visited last year, the guide, lamenting, said, ‘Don’t allow this to happen when you are united,’” Seung recalled.

Does he have a favorite project? “I don’t visit buildings that I designed,” he says, likening going to dedication ceremonies and awards ceremonies to being dragged to a slaughterhouse.

The one exception is Sujoldang, which he visits from time to time. Built in 1993 for art historian and former Cultural Heritage Administration chief Yoon, the house embodies Seung’s philosophy of “beauty of poverty” with its many voids, including madang, the courtyard.

“It is the first piece of ‘Seung Hyo-sang architecture.’ It is a house that I must remember,” he says.

By Kim Hoo-ran (

khooran@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)