Ever since he hopped in jazz music as a teenager, he wandered and snooped around all sorts of electronic shops, particularly radio stores, to find anything related to jazz. From magazines to LPs.

“I spent every day looking for John Coltrane and Miles Davis’ records, but it was extremely difficult, especially since Elvis Presley was everything in Korea at that time.”

One day good fortune smiled on him, as he was lucky enough to discover lots of jazz records at a small record shop at the country side.

“I found thousands of LP jazz records there that the owner was about to sell for a raw material plant. So I paid 50 won a piece.” Later, he sold some of them for 5,000 won a piece, but he did not make much money ― he couldn’t part with many of them, and bought more records with the proceeds.

His life was nothing but jazz. Once he was kicked out of his apartment as he spent all his rent money on jazz records.

Single-minded as his love for jazz might be, his future was not always bright.

“I got married when I was 22 years old, but one day, my wife ran away because all I did was listen and play jazz in the house. My wife had thought I neglected the family, so she ran away with our four daughters.”

All his energy put in jazz finally began to pay off after he worked in the 8th U.S. Army military band. He spotted a jazz drum contest poster, and when he went to watch the show, a TV producer who knew him recognized him, took him to the stage immediately and introduced him to the big-time percussionist Lee Bong-jo, who then scouted him as one of his band members. Since then, he has shone as a professional jazz percussionist.

“When most of Korean jazz musicians fled overseas because of a hard and poor life for jazzmen, I remained firm. I stayed to struggle for jazz to take root in Korea. I really fought for it.”

During the administration of President Kim Young-sam, there was a law restricting musical performances. The law allowed only cabarets and night clubs to feature bands. The law was applied strictly. No band was allowed to play inside cafs or restaurants, where only solo performances were permitted.

“A band like us would be playing secretly, so we were chased by police. We did that for 20 years. When we were caught playing in cafes or restaurants, we were treated as if we had committed serious crimes. We just performed jazz as a band. Korea was then culturally rotten.”

Ryu did not give up hope. Along with a singer-turned-lawmaker, Choi Hee-jun, and the owner of “For a Thousand Years,” the country’s biggest jazz club, he fought to repeal the law.

“After Kim Dae-jung became president, the government eased the law. Since then, we have been able to play wherever we wanted. It is a great milestone in Korean jazz history,” he said

So, did jazz ever get into the limelight?

“Not so much, at least judging by how much pay we earn from performing.”

The jazz industry has slowed down these days, he said, adding that the jazz market was not out of the recession yet.

“The pay we get is unreasonably low. For old fellas like us, it’s okay, but thinking about how much the young jazz musicians get, it’s ridiculous.

“If I appear on TV as a guest in Japan, they would pay me a guarantee of 50 million won. So, one-time contract would be good for a year of living. But in Korea, I would be paid 500,000 won per appearance without guarantee. And the pay we get for performing at a jazz club in Korea is sadly low.”

According to Ryu, state-sponsored art halls and concerts are reluctant to invite expensive A-class bands any longer.

“Since they can afford to invite more C-class bands with less money.”

Still, he does not mind the low pay. Ryu hold as many gigs as possible purely for his love for jazz and his long-cherished dream to see it bloom in Korea.

These days he can be seen at almost all famous jazz joints in downtown Seoul ― from Once in a Blue Moon in Chungdamdong, All that Jazz in Itaewon, For a Thousand Years in Daehangno, KT Art Hall in Gwanghwamun and Moon Glow in Hongdae.

Despite his busy schedule, he recently released a 50th anniversary DVD album, “Jazz Concert at Jazz Park.”

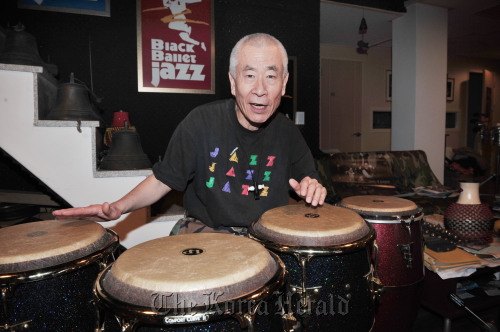

Following the release of the album, he plans to hold a jazz concert as a band of seven legendary pioneers of Korea’s first-generation jazz. They are jazz clarinetist Lee Dong-ki, 75; vocalist Park Sung-yeon, 68; tenor saxophonist Kim Soo-yeol, 73; trumpeter Choi Sun-bae, 71; jazz vocalist Kim Jin, 72; jazz pianist Shin Kwan-woong, 67. Ryu will play bongo and drums.

The gig kicks off at 8 p.m. Jan. 28, at the Concert Hall of the Seoul Arts Center. Next generation jazz artists will also take to the stage together as guests.

The young jazzmen are Lee Jung-sik (saxophone), Malo (vocal), Lim Hun-soo (drum), Jang Eung-gyu (bass), Lim In-gun (piano), Lee Han-jin (trombone), Kim Ye-joong (trumpet) and Lee Kyung-woo (vocal). They will accompany their seniors to bridge between the two generation jazz musicians.

At the performance Friday, vocalist Malo will sing with Park Sung-yeon, and saxophonist Lee Jung-sik will perform with Kim Jun for the song “My Way” to round out their performance.

The master percussionist Ryu will play throughout the concert. “Just because the band name is Latin Jazz All Stars doesn’t mean that we only play Latin jazz.”

With his drums, bongos, congas and timbales, his music covers big band-style swing of the ‘30s and ‘40s, bebop of the mid-’40s, a variety of Latin jazz fusions of the ‘50s and ‘60s, fusion jazz of the ‘70s, and Nu-jazz of the ‘90s.

As always, he will do it with his signature twist. In most gigs, Ryu lines up famous jazz songs and adds self-written Korean lyrics, such as “Mo Better Blues,” which he renamed “I Want to Fall in Love.”

By Hwang Jurie (

jurie777@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)