LOS ANGELES ― No place tells the story of modern aviation better than the skies over the desolate Mojave Desert surrounding Edwards Air Force Base.

This is where a 24-year-old Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier flying a fat orange jet called the Bell X-1 in 1947, and where the sleek rocket-powered North American X-15 became the first airplane to reach outer space in 1963. The space shuttle made its first landings here too.

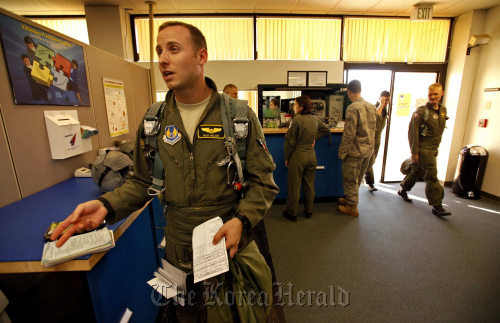

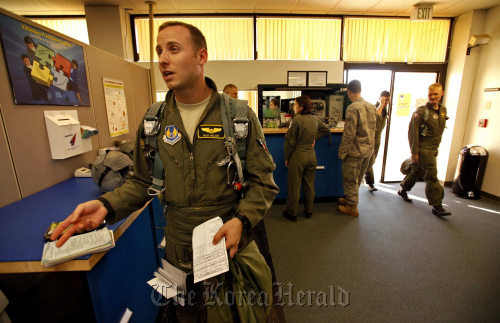

U.S. Air Force Capt. Nicholas “Hammer” Helms is in line to be the next aviator to make history at Edwards. But he won’t be breaking any speed records or risking his life to push the limits of what aircraft can do.

Instead, he’ll do his test-flying from a computer workstation, safely on the ground. Helms is being trained to be the nation’s first drone test pilot.

“Flying at 9 Gs is a lot more fun than sitting in a locked room, I’ll tell you that,” said Helms, 29. “I never expected to be flying anything other than an F-16. But now I’m here.”

|

Air Force Captain Pilot Nick “Hammer” Helms returns from his one hour training flight aboard a T-38. (Los Angeles Times/MCT) |

Helms’ admission into the elite U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards is another sign of the Pentagon’s historic shift to drones, which are cheaper to build and operate than conventional aircraft. Thousands of propeller-powered Predator and Reaper drones are already deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and military contractors are now testing more advanced versions with jet engines and increased lethal firepower.

Shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks more than nine years ago, the Pentagon rushed drones into combat. Unlike conventional aircraft, drones did not undergo the rigorous test regimen that the military typically puts planes such as fighters and bombers through. Drone test flights were conducted by engineers and pilots unfamiliar with the burgeoning technology.

It will be Helms’ job to give feedback to contractors building the drones and develop the protocols for flying them.

“There’s obviously a need for what we do,” said Col. Noel “Shamu” Zamot, commandant of the Edwards test pilot school and a former B-2 bomber pilot. “These are intricate systems that need a pilot’s input to tell a manufacturer what works and what doesn’t.

To some purists, however, Helms will never be in the same league as those who take to the skies in unproved experimental aircraft. More than 320 people have lost their lives in accidents at Edwards, many of them related to test flights.

“He’ll never be a true test pilot,” said Billie Flynn, president of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, who is now test-flying the F-35 fighter jet for Lockheed Martin Corp. “He can never boast that he’s from the land of ‘Right Stuff.’ It’s not his pink body that’s being put at risk.”

Helms never set out to be a drone pilot. After graduating from the U.S. Air Force Academy near Colorado Springs, Colo., Helms wound up training at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona, where he ripped through the sky at 1,500 mph above the sun-scorched Sonoran Desert in F-16s. As an F-16 pilot, he beat out higher-ranking officers in bombing contests and was named the “wingman most desired in combat” by his instructors.

Then on June 29, 2007, the day after his 26th birthday. Helms was home visiting his parents in Apple Valley, Minn., when his commander called to tell him he was being reassigned to Creech Air Force Base near Las Vegas.

His new assignment: piloting Reaper drones by remote control.

“It felt like I was hit in the stomach,” Helms said.

Despite his initial disappointment, Helms grew to like coordinating sorties with troops on the ground.

“It’s very rewarding to hear the guys you’re helping,” he said. “I don’t think you can get the same experience flying fighters.”

Helms learned two years ago that the school at Edwards was offering one of its 12 slots for a drone pilot. He submitted his application.

“I think every Air Force pilot wants to be at Edwards at some point in their career,” Helms said. “It is enthralling to be in the world’s premier test pilot school.”

At the school he flies the old-fashioned way: up in the sky. And he pilots a variety of planes ― including fighters, giant fuel tankers and small turboprops ― to expand his aeronautic vocabulary.

On a recent day, the sun was rising over the desert when Helms, helmet in hand, walked down the flight line and clambered into a T-38 trainer jet. Helms maneuvered the jet onto the runway and took off, climbing to 35,000 feet.

Helms’ mission was to measure the jet’s performance in different configurations. He twisted the plane at high speeds and felt strong G-forces pushing down on the aircraft. Then Helms accelerated and, with that, a sonic boom reverberated over the desert floor as he took the jet supersonic.

An hour later, Helms was finished. Climbing out of the cockpit, an amped-up Helms immediately began analyzing his flight. He talked about the plane as it approached Mach 1, excitedly talking about the effect of pressure building up on the airframe as the speed increased.

Having experience both in the cockpit and at the computer, he knows that remotely piloting planes has its own skill set, which is sometimes at odds with what he learned flying jets.

“My focus is on fixing the design errors and communicating the requirement for good design,” he said.

“Growing up, I had examples of fighter aircraft to dream about piloting ― and that seemed fun,” Helms said. “You’ll have to ask today’s 10-year-old boys and girls which is more fun, fighter piloting or remote piloting.”

By W.J. Hennigan

(Los Angeles Times)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)