What makes portraits different from other paintings?

The substance of its subject, scholar Cho Sun-mie answers.

An English edition of Cho’s book on Korean portrait paintings and their stylistic development ― mainly of the ones from the Joseon Dynasty (1392―1897) ― has been published.

The book, “Great Korean Portraits: Immortal Images of the Noble and the Brave,” introduces portraits of 50 prominent individuals who carry great importance in Korean art history.

The figures include King Taejo of Joseon, Confucian scholar Yi Hyeon-bo, renowned self-portrait artist Yun Du-seo, and the martyred Joseon female entertainer, or “gisaeng,” Gyewolhyang.

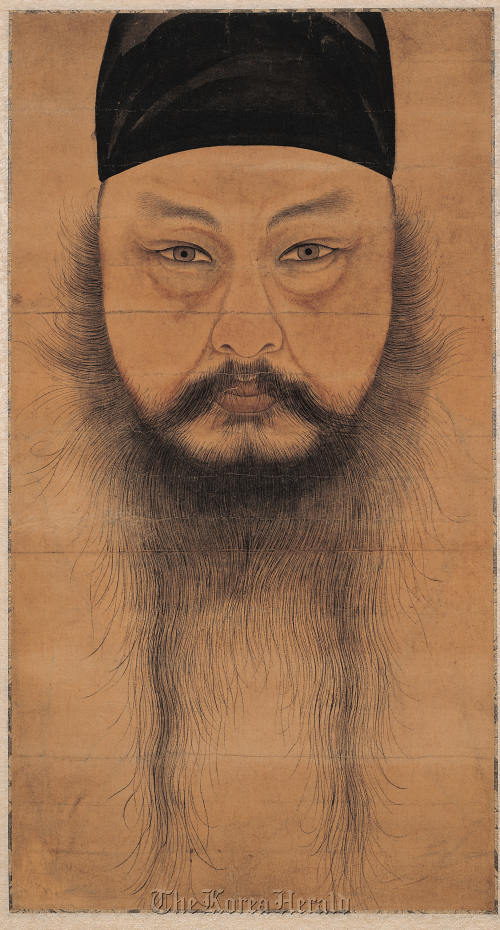

|

Portrait of Gyewolhyang (?-1592), a famous “gisaeng,” or traditional female courtesan, based in Pyongyang. (Dolbegae Publisher)s |

Cho, who spent the last 35 years researching portraits, especially those from Korea’s Joseon Dynasty, says it’s the ancestral rituals that had a deep connection with Joseon’s portrait art.

“Because Joseon was a Confucian society, its people stressed the importance of respecting one’s roots and ancestors,” Cho says.

“As the ancestor rituals became important, portrait paintings became popular during the ceremonial process. As a result, many portrait paintings were produced throughout this time.”

Though Cho had always been interested in portrait paintings, her major concentration of research was on Western art until she completed her master’s degree.

"I even moved to the United States with my husband to do my PhD degree in Western art,” Cho says. “But we had to return to Korea because my husband ran into an accident not long after we settled in the states.”

After she returned to Korea, Cho decided to write her doctoral dissertation on Korean portraits instead.

“If I were to study art for a long time,” Cho said. “I thought it would be more meaningful to study our art.”

According to Cho, Joseon’s portrait paintings exhibit extremely detail-oriented and realistic depiction of their subjects.

“How such trend began is rather funny,” Cho says. “Joseon was greatly influenced by Chinese Confucian philosopher Cheng Yi (1033-1107). And one of his statements said, “If even one hair is not correctly rendered, then the image portrayed would be that of another person.” Cheng in fact said this to discourage painters from painting portraits, as he thought it wasn’t humble enough ― by his strict Confucian standards ― to have portraits during the ancestral rituals.”

Not knowing Cheng’s initial intention, painters of Joseon took the statement literally and applied to their works of art.

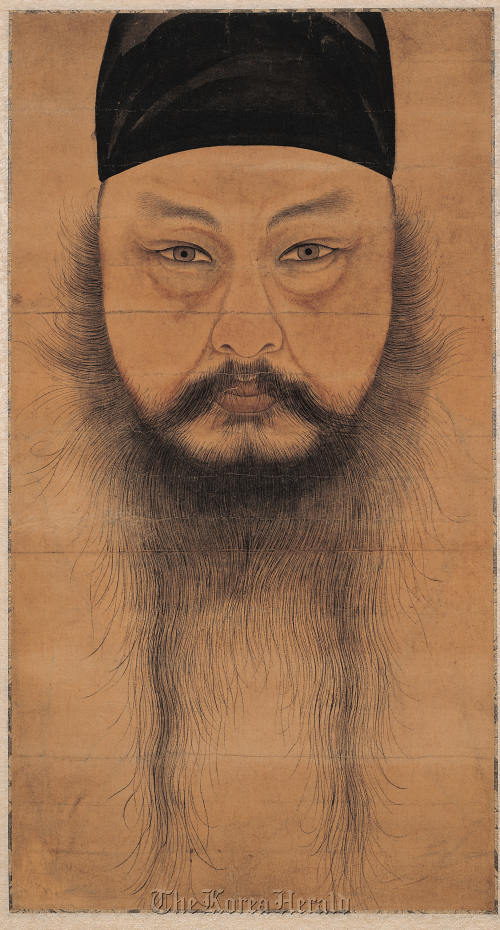

One of the greatest examples that reflects Cheng’s such statement is the famous self-portrait of Yun Du-seo (1668-1715). An extremely detail-oriented work of his own face, it is considered one of the most significant and powerful works of realism.

|

Self-portrait of Yun Du-seo. National Treasure No. 240. Dolbegae Publishers (Dolbegae Publishers) |

“It is a monumental work,” Cho said. “There is no narcissism and no staging. It shows an individual who has studied and analyzed himself strictly from the third perspective.”

Cho says one of the reasons why Korean portrait paintings are so engaging is because of their subjects: “Great painters met great people of the time. These historical figures had such layered and rich inner qualities.

“And the painters caught those substances and showed them in their paintings,” she said.

By Claire Lee (

clairelee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)