A restlessness in her soul would not let Gloria House be.

She was a graduate student in 1963 studying French at the University of California at Berkeley.

But how could she study when four little black girls were blown to bits by dynamite that tore through their Birmingham, Ala., church? And when the bodies of three boys ― two white, one black ― who’d gone south to help black people, were found buried on a Mississippi farm?

Those incidents and other examples of racial injustice called House to go to the Deep South in 1965. She planned to go just for the summer to help teach black people to read and to register to vote. But while she was there, a fellow freedom fighter, a white seminarian, was shot and killed right before her eyes.

“Being a graduate student seemed insignificant compared to a life and death struggle,” says House, now in her 60s and living in Detroit. Within a week of returning to school, House was back in Alabama where she worked until 1967 organizing, teaching and protesting as a part of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.

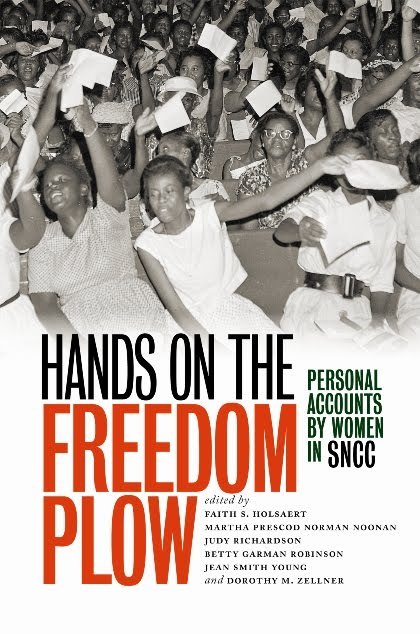

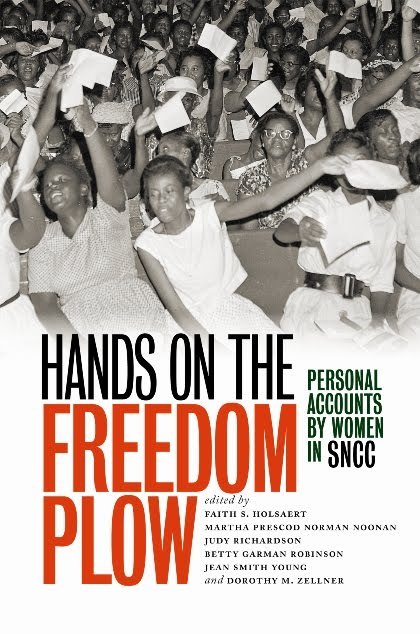

House’s story is one of 52 featured in the new book “Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC” (University of Illinois Press, $34.95). The book is edited by six women, including Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, an activist and history teacher. In sometimes frightening, occasionally humorous and often inspiring accounts, the women featured in “Freedom Plow” tell of the varied and valued roles they played, registering people to vote, organizing and running meetings and teaching in the face of fear.

“A great deal of the existing history has highlighted the roles of men,” says Noonan, who was an 18-year-old University of Michigan sophomore when she first went south in 1963. “Women played key roles and that needs to be recognized.”

Among the women featured in the book are Denise Nicholas, whose successful acting career began when she performed as a part of the freedom struggle in Mississippi in 1964; Jean Wiley, a retired educator and journalist who went to Alabama in the summer of 1964 after completing her master’s degree at the University of Michigan; Marilyn Lowen, a poet now living in New York, and Gwen Patton, a retired archivist who now lives in Montgomery, Ala.

|

“Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC” |

The women were drawn to different places in the Deep South in the 1960s, but they shared a passion and commitment that helped them weather daily dangers. Each one says their involvement not only changed the country, it shaped who they became and it created a bond that connects them still.

“What we did changed the course of American history,” says Nicholas, who also was a U-M student in 1964 when she decided to go to Mississippi. She took a series of trains alone from Ann Arbor and signed up to help on the just-beginning Free Southern Theater project, an effort to entertain, educate and reflect the Southern condition. She offered to help read and critique scripts, but the group said it needed her to act.

The theater company toured small towns throughout the region, eventually settling in New Orleans, often performing in cotton fields and churches and community centers in the black section of town while armed townsmen stood guard on porches to protect them.

“People were very responsive to seeing something about the life they had lived or the life someone in their family had lived reflected on the stage,” recalls Nicholas, who now lives in the Los Angeles area. “It gave a way of speaking thoughts they had been thinking and not been able to express.”

Nicholas says that although they were scared all the time, the students were able to “ride on top of our terror” because of the unity and energy between the freedom workers and the townspeople.

“You could sense, you could feel the awakening of the people themselves,” Nicholas says. “The local people, many of them, were very afraid. But you could feel a change in the air that was palpable. Some of them had already lost their jobs or had their homes burned down and yet they continued coming to our plays and to the schools.

“Oftentimes, they sat on their porches with shotguns in hand to protect us while we slept. I was constantly afraid, but there was fear and a kind of youthful bravado that you’re immortal. And we were surrounded by like-minded people. We felt (that) if these people can live here and do this, we can, too. There was a certain amount of coming-of-age for each one of us.”

Looking back on it, House says she is not sure how they worked in the midst of danger.

“We were traumatized, yet we didn’t stop,” says House. “I truly don’t know how to explain why we didn’t run away. We just sort of pushed back the fear and kept stepping into the next day because there was so much work to do.”

The women dispute reports that female civil rights activists were forced to be second-class citizens in the movement. Women did everything men did, they say, from riding mules and planning strategy to directing field staff on northern campuses and rural plantations.

”SNCC was the only time in my life that my gender was not a barrier to my aspirations,” Wiley wrote in her account.

House settled in Detroit after she left the South and built a successful career as a writer and educator.

She and the others hope the book not only fills in gaps of history, but offers timeless lessons to today’s generation.

“I hope that youngsters today understand that the work they do can have enormous impact,” she says. “The work we did inspired the women’s movement. It inspired other communities of color. You shouldn’t underestimate the impact you can have as young organizers if you’re determined.”

By Cassandra Spratling

(Detroit Free Press)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)