400-year-old translation still commands a loyal following

CHICAGO ― On its 400th anniversary, the King James Version of the Bible is universally recognized as a literary masterpiece that profoundly shaped both modern Christianity and the English language.

But at the Bible Baptist Church in Mount Prospect, Illinois, it’s accorded a much higher level of reverence.

“Using anything but the King James Version,” said Chris Huff, the church’s pastor, “is like shaving with a banana.”

The suburban Chicago church belongs to a loosely defined denomination known as the “King James Only” movement. Members believe the King James Version is not just another translation but the indispensible underpinning of a Christian’s faith.

“When I’m looking for a church, the King James Bible is non-negotiable,” said Sandra Maio, after a Wednesday-evening Bible study class there.

As it heads into another century, the King James’ achievements are being heralded around the world. Actors will recite every word from Genesis through Revelation at London’s Globe Theatre, this Easter season. Celebrations are scheduled in the hometowns of the 47 British translators who produced a work Winston Churchill called a “masterpiece” and George Bernard Shaw saluted as “magnificent.”

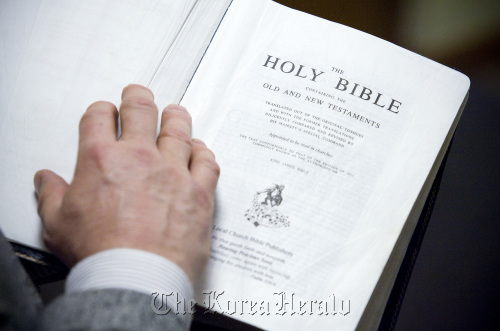

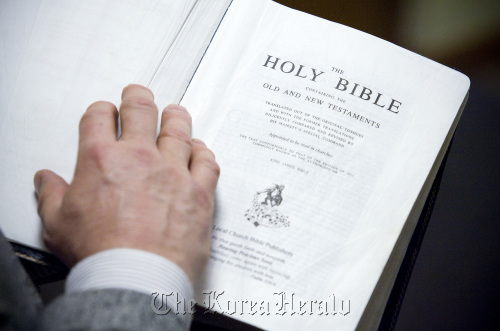

|

Pastor Chris Huff, of Bible Baptist Church, in Mount Prospect, Illinois, holds his copy of the King James translation of the Bible. (Chicago Tribune/MCT) |

At seminars and lectures, it will be noted that the King James’ cadences and phrasings echo in Abraham Lincoln’s speeches and Paul Simon’s lyrics.

Yet on a daily basis, most churches use an updated version or more contemporary translation, reserving the King James’ richly poetic language for weddings and funerals.

When James I of England set his committee of translators to work in 1604, England was on a religious roller coaster.

Under James’ royal predecessors, England had bounced between Catholicism and the Protestant wings of the Reformation Era. With each reign, new articles of faith were adopted, others discarded. Believers whose convictions were momentarily out of date were sent to the gallows or burned at the stake.

From the perspective of the throne, a Bible was needed that would command respect ― an English version that, as the translators wrote in their preface, “containeth the word of God, nay is the word of God; as the King’s speech which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian and Latin, is still the King’s speech.”

Pastors of “King James Only” congregations feel much the same way. Some believe the King James version to be every bit as divinely inspired as earlier Hebrew and Greek texts.

Gordon Campbell, author of “Bible: The Story of the King James Version 1611-2011” reports that more than 1,000 churches worldwide subscribe to a statement of faith that this 400-year-old translation “preserves the very words of God in the form in which He wished them to be represented in the universal language of these last days: English.”

Huff thinks the King James Version was produced at exactly the right moment in history. Renaissance scholars had revitalized Greek and Latin scholarship, producing new texts of the Old and New Testaments. The printing press made it possible to spread knowledge faster than ever before.

And the English language was at a high point of expressiveness ― William Shakespeare died five years after publication of King James’ Bible in 1611.

To that list, David Norton, author of “The King James Bible,” would add the political savvy of its translators.

“It’s most striking the degree to which their text is theologically neutral,” said Norton, an English professor at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. He notes the version didn’t contribute to arguments among churchmen, no mean feat in an age of bitter disputes over religious doctrine.

Norton and most university-based Bible scholars don’t subscribe to Huff’s conception of a once-and-only translation storm.

“The King James Bible is a monument to English poetry and prose at one of its greatest moments,” said Richard Rosengarten, a University of Chicago professor who studies the intersection of literature and religion. “But if it’s so great, why are there so many other translations?”

In fact, the English in the King James Version was already a bit archaic in its own day, according to Rosengarten and other scholars. “Thee” and “thou” were passing out of everyday speech. So to 21st century young people, it can seem as remote as Latin.

Many subsequent translations ― the Revised Standard, Phillips New Testament in Modern English, New English Bible ― were inspired by the idea that language evolves. Ancient manuscripts discovered since King James’ day give modern scholars a broader view of biblical texts.

Such is the power of the King James Bible that even nonbelievers honor it above all others ― as do lapsed Protestants like Frederick William Faber. A 19th century English writer who converted to Catholicism, Faber never forgot the majesty of the King James Bible of his Methodist youth.

“It lives on in the ear like music that can never be forgotten,” he wrote, “like the sound of church bells, which the convert hardly knows he can forget.”

By Ron Grossman

(Chicago Tribune)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)