Singer-songwriter’s new book tells story of fictional English composer

John Wesley Harding is Wesley Stace.

That is, Wesley Stace is John Wesley Harding.

That is, they’re the same person. Folk-rocker Harding ― intelligent, bardic songwright ― is the nom de rock of Wesley Stace, novelist, whose splendid new book “Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer” is out now.

As usual, all sorts of things are afoot for Stace. He and family moved from Brooklyn to Philadelphia in July. (His wife, the artist Abbey Tyson, is from Philadelphia’s Chestnut Hill neighborhood.) “It seems almost inevitable in a way, doesn’t it, moving here?” Stace says. “I absolutely love it, and it’s always been good to me. I think I did my first gig for (University of Pennsylvania public radio station WXPN-FM), oh, it must have been 1990.”

But the move also was a matter of family, of raising daughter Tilda, 4, and son Wyn, 2. “We loved Brooklyn,” Stace says, “but with children, everything we wanted to do together became a military exercise.”

On top of that, Stace, 45, is doing gigs, as he’s done since the 1980s; book tours, at which he plays guitar, or maybe brings along a classical quartet (“I’m trying to change the whole idea of a book reading,” he says); putting on the Cabinet of Wonders variety shows in New York, featuring artists and musicians such as Janeane Garofalo, Andrew Bird, Jonathan Coe, and Tift Merritt; being an artist in residence at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey; and collaborating across music and literature in a mindload of ways. And since 2005, writing critically acclaimed novels.

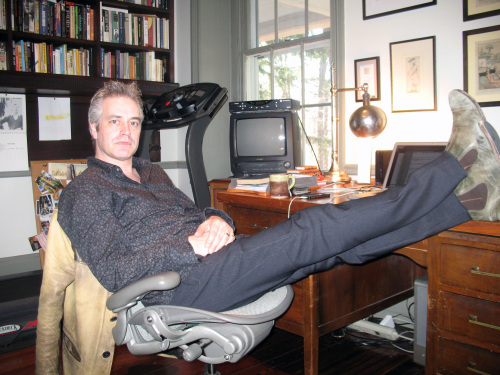

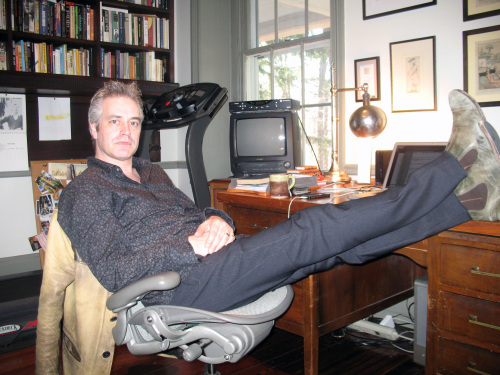

The folkie/novelist fidgets in the spacious, book-lined study of his West Philadelphia house and says, “You catch me at an extremely interesting moment. My entire approach to songwriting has changed ― not in the album I’m finishing now, but it will.” (That album, preliminarily titled “The Sound of His Own Voice,” has as backup band the revered Decemberists, minus lead man Colin Meloy, and should be out this year.) “I think the novels have released me to write songs that perhaps are less literarily focused, and more focused on powerful things in my life.

“I realize now that my life’s project, what I was put here to do, was to put literature and music together in new ways,” Stace says. For years, his songs, which are short stories of the soul, with rich, expressive, surprising lyrics, have done that ― but so, in a quite different way, does his third novel, “Charles Jessold.”

|

Wesley Stace relaxes in the study of his West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania home. (John Timpane/Philadelphia Inquirer/MCT) |

It follows the life of Jessold, a fictional English composer of the early 20th century. His music is first adored, and later not adored, by a hidebound, snarky critic named Leslie Shepherd. Shepherd wants Jessold’s music to tell a certain story, but when it begins to tell another, he can’t forgive it, or Jessold.

“What this book is massively about,” Stace says, “is how criticism distorts art by reducing it to handy narratives that tell the story people like to hear.”

Not to mention the killings, assumed identities, and murder mysteries, an opera that tells the story of the murders, and a layered and relayered story that tells itself in different ways. Add an eerie parallel deep in the past: Carlo Gesualdo, a real 16th-century Italian composer, whose name in English turns out to be ― oh, yeah. As the story and its telling move forward, Shepherd feels it starting to control his life. It’s one of the few thrillers that really does get better as it goes along. The first half is interesting, but the second half fascinates; the first half engages, but the second half compels and obsesses.

Stace, characteristically, has seen the thing all the way through. He got composer Daniel Felsenfeld to write a suite of five “Jessold” songs ― written to reflect the fictional Jessold’s midplace between the “English movement” in music just before World War I and European atonal music. “Jessold’s” music has been played at concerts in Berkeley, Calif., and New York. “The consort sings the tunes, and I read from the book, from Shepherd hating them,” Stace says.

His interest in literature is easily explained. Born in England in 1965, he got a first degree (the highest possible) in English at Jesus College, Cambridge, but left before completing a Ph.D. He has lived in the United States since 1991. He knows huge amounts about folk and rock, but his knowledge of classical music “was a product of a lot of mad studying,” Stace says, “plus some wonderful consultation with Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker.”

Stace is a whirlwind. He speaks of music, literature, and art with the same wide-eyed intensity. He proudly displays his vinyl record collection. He goes into transports when the 1970s Cambridge band Caravan, or any prog-rock, is mentioned ― and again when he rushes to show his original edition of Laurence Sterne’s “Tristram Shandy,” signed by the author. (Sterne and Shandy play roles in the novel.)

David Daniel is the director of creative writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University. Stace, he says, is “totally lovable,” some strange superhuman being who’d be killed by the rest of us out of envy if he weren’t such a nice guy.“

Daniel has roped Stace into a range of activities, including the artist-in-residence gig, and performance in WAMFest, the spring Words and Music Festival at Fairleigh Dickinson. Last year, Stace shared a stage with former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky and that other much-laureled poet, Bruce Springsteen.

“Wes turned it into this fantastic event,” Daniel says. “He’s one of these people who crosses many genres effortlessly, and he’s got a wonderful sense of humor and a lack of attachment or ownership of projects. No matter the project, with Wes there’s always this sense that ‘We’re all going to have a great time.’”

Daniel introduced Stace to another literary rocker, Paul Muldoon, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and Princeton professor. (Muldoon rocked for years with a band of his own, Rackett.)

“I’m a huge fan of Wes,” Muldoon says. “He does seem to be able to do several things at once, and do them very well.”

But people say that if you try to do too many things, you end up doing nothing well, don’t they?

“One of the great delights of being in the world is that you can try several things,” Muldoon says. “And not only does Wes try them ― he’s very good at them.” He’s a fan of both Stace’s music (“he’s a real rocker”) and his words: “The quality of his lyrics is particularly high.”

In fact, Muldoon and Stace are working on an album together. “Paul and I have worked up about 10 or so songs,” Stace says.

Muldoon has put his finger on it: The keys to Stace are fearlessness and a wide-ranging, heady playfulness. Sure, the songs have the lit references, but you needn’t have cracked a book to enjoy them. Same for “Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer”: You needn’t have heard a note of Ralph Vaughan Williams or Carlo Gesualdo to get snagged in the tale. Stace/Harding is a master of the sleight-of-hand that makes what threatens to be merely erudite into something that’s beckoning and enjoyable.

Take the tune “Oh! Pandora” on the John Wesley Harding CD “Who Was Changed & Who Was Dead.” The speaker says to Pandora, who’s trying hard not to open that darn box:

Sister, you just can’t resist

Neither can I

And it never hurts to try

It’s my turn

Wesley Stace, be he Stace or Harding, much-praised novelist or much-praised singer-songwriter, is not afraid to try. It hasn’t hurt so far ― in fact, his turn is working out nicely.

By John Timpane

(The Philadelphia Inquirer)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)