British Prime Minister suffers from ‘rebellion’ within his Conservatives

LONDON (AP) ― British lawmakers on Monday overwhelmingly rejected a motion to hold a national referendum on leaving the European Union, but Prime Minister David Cameron suffered a bruising as several Conservative Party lawmakers rebelled against his orders and supported the bid.

The revolt within the ruling Conservative Party ranks underscored discontent with Cameron’s stewardship ― an unhappiness that has grown following his handling of riots that gripped the nation in August and his decision to hire a suspect in Britain’s phone-hacking scandal.

The motion for a referendum ― which was not binding on the government in the first place― was handily defeated, with 483 lawmakers voting against having one and 111 voting in favor of it.

The government had ordered its lawmakers to vote against the referendum on whether Britain should remain in the EU, leave it, or re-negotiate membership, and said those who backed it would face disciplinary action.

House of Commons leader Sir George Young told the BBC he believed 80 or 81 Tory MPs had rebelled

In a last ditch attempt to sway would-be rebels in his party, Cameron insisted the current economic crisis meant the “timing is wrong” to abandon the EU. But his appeal failed to resonate with several Conservatives ― a fact highlighted by dramatic proclamations from lawmakers during a more than five-hour debate that they would back the referendum despite the personal cost.

Conservative lawmaker Adam Holloway resigned his unpaid post as an aide to Europe minister David Lidington so he could vote in favor of a referendum.

“If you can’t support a particular policy then the honest course of action is of course to stand down, and I want decisions to be made more closely by the people they affect, by local communities, not upwards towards Brussels,” Holloway announced to cheers in the chamber.

|

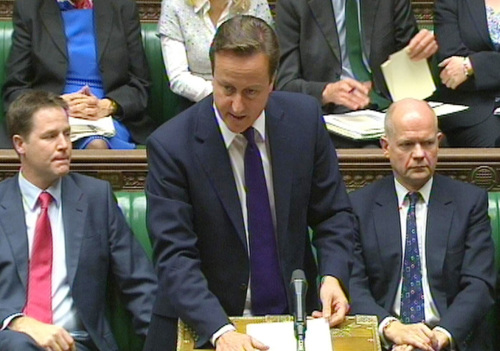

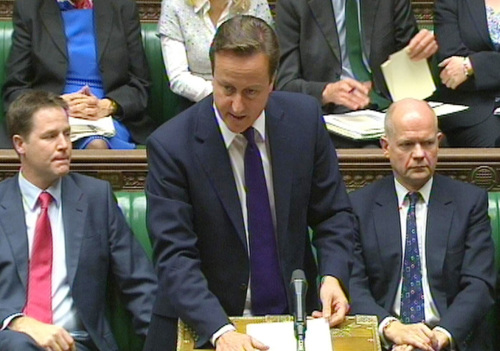

U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron (center) addresses the House of Commons in London on Monday. (AP-Yonhap News) |

Fellow Conservative Stewart Jackson said he was prepared, “with a heavy heart,” to “take the consequences” of rebelling against the government order.

“For me constituency and country must come before the baubles of ministerial office,” he told his fellow lawmakers.

Britain’s role in Europe was once a bitterly divisive issue for Cameron’s Tories, with the 1980s and 1990s marked by internal conflicts between those advocating closer links with the EU and legislators who favored leaving the now-27 nation bloc.

Former Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher famously railed against a “European superstate exercising a new dominance from Brussels,” but found herself at odds with many pro-European cabinet ministers.

The issue of Europe has also split Britain’s current governing coalition. The Conservative Party’s junior partners, the Liberal Democrats, are strongly pro-Europe.

Although a member of the EU, Britain is not among the 17 countries that use the euro single currency and are struggling to hammer out a bailout for debt-laden Greece.

Cameron’s leadership has weathered fierce criticism in recent months for a slew of perceived missteps.

Cameron’s judgment has repeatedly been called into question by his decision to hire as his communications chief an ex-News of the World editor implicated in the phone-hacking scandal at the now-shuttered tabloid. The prime minister’s stature also took a blow when riots swept Britain in August. He was accused of a feeble initial response.

The prime minister also has been accused by critics of changing his tune toward Europe since being elected and doing too little to challenge EU legislation or European court rulings. He pledged Monday to wrest more powers away from Brussels and agreed that there is a need for fundamental EU reform. But he said it is in Britain’s national interest to remain part of the EU and noted that the eurozone is in dire straits economically.

“When your neighbor’s house is on fire, your first impulse should be to help them to put out the flames ― not least to stop the flames reaching your own house,” Cameron said in a statement ahead of the vote. “This is not the time to argue about walking away, not just for their sakes, but for ours.”

Monday’s debate was triggered by a 100,000-signature public petition on the prime minister’s website.

Foreign Secretary William Hague, a longtime euroskeptic, said that with the EU mired in a debt crisis and Britain’s economy fragile, a referendum “would create additional economic uncertainty in this country at a difficult economic time.”

“Europe is undergoing a process of change and in an in-out referendum people would want to know where the change was going to finish up before they voted,” Hague told the BBC. “Clearly an in/out referendum is not the right idea.”

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)