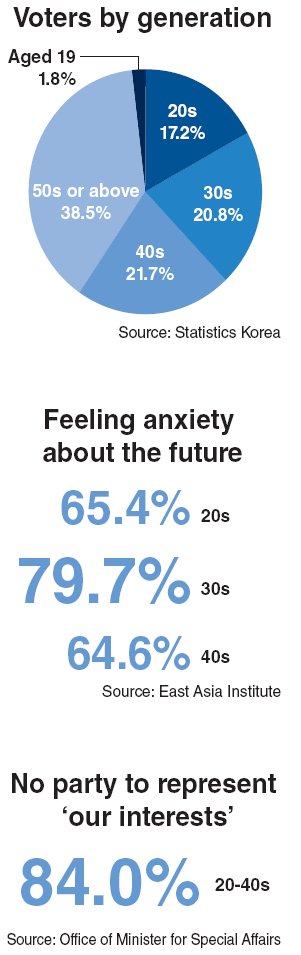

According to a joint exit poll by three major broadcasters, a majority of voters in their 20-40s ― 69.3 percent for 20-somethings, 75.8 percent for 30-somethings and 66.8 percent among 40-somethings ― cast ballots for the liberal civic activist. In contrast, a larger bloc of senior voters ― 56.5 percent among those in their 50s and 69.2 percent for people in their 60s or above ― voted for the GNP candidate.

The election outcome is tantamount to an “outcry from the classes constituting the ‘waist’ of Korean economy,” said GNP lawmaker Won Hee-ryong, a member of the party’s Supreme Council.

What bound the younger electorate in rallying around the nonpartisan candidate, political observers note, was anger with the failure of the political establishment in addressing their immediate concerns.

The support rates for Park among the voters in their 20-40s were closely overlapped with the ratios of people who expressed worries over their future in a survey conducted by the East Asia Institute earlier this year. The survey showed a sense of angst gripped 65.4 percent of 20-somethings, 79.7 percent of 30-somethings and 64.6 percent of 40-somethings.

Sense of marginalization

Going through a string of economic crises over the past decade, those in their 20-40s, described by local media as the 2040 generation, have come to share a feeling of being marginalized from society and deprived of opportunities their preceding generations had enjoyed in the era of fast economic development, analysts say.

Many people in their 20-30s have never gotten on the ladder to lead them to the upper class while those in their 40s were pushed off it midway, they say.

Although they face different problems in different phases of life ― high college tuition fees, unemployment, child care, education and housing costs and preparation for old age ― the 2040 generation share a mounting feeling of frustration that the weight pushing down on their shoulders may be insurmountable for them.

The younger generation feels that their path toward self-achievement has been unduly blocked by vested interests, losing respect for the older generation.

“The generational rift in our society is too extreme,” said Kim Mun-cho, professor of sociology at Korea University in Seoul.

“Younger and older generations have different views of what has caused the current hardships and how to overcome it,” he said.

While older people, who grew in the era of rapid economic development, believe it is mainly up to individual people to go through difficulties, those in their 20-40s think the problems facing them reflect an irrational social structure and result from policy failures, according to the professor.

Analysts also note there is a lack of communication between the younger and older generations, who resort to different means to gain information and communicate with other people.

While those in their 20-30s are adept at the use of social media and instant communication, many people in their 50s or older still rely on conventional media such as newspapers and TV.

Such differences made the two generational groups “two islands separated from each other in society,” said professor Kim.

Those in their 40s appear sandwiched between the groups with some progressive figures trying to spread the sentiment of the younger generation among the age group.

No political affiliation

The 2040 generation, who is now calling for distribution of wealth to be put ahead of growth, feel betrayed by President Lee Myung-bak, whom most of them supported in the previous election, pinning hopes on his pledges to ease their suffering. They now see Lee’s policies have only increased profits for large corporations and made the rich richer, exacerbating the predicament of the low-income, working class. In the EAI survey, more than 70 percent of the age brackets said the Lee government represented the “interests of the few, not the many.”

Their ire is also aimed at the major political parties, which they denounce for having been preoccupied with partisan wrangling, paying little attention to matters related to their livelihoods.

In a survey of about 1,200 people aged 20-39, conducted by the office of the minister for special affairs in June, more than 80 percent of the respondents said there is no party to represent their interests.

“I think there is no difference between the ruling and opposition parties in their insensitivity and inability to address our urgent problems,” said a 32-year-old company employee surnamed Han.

The younger generation’s disillusionment has translated into enthusiastic support for entrepreneur-turned-professor Ahn Cheol-soo, who has taken a nonpartisan stance emphasizing common sense beyond partisan standoffs in resolving the current difficulties facing the nation. Recent opinion polls have shown him far ahead of possible opposition presidential runners and neck and neck with GNP’s presidential front-runner Rep. Park Geun-hye in approval rating.

The main opposition Democratic Party and other liberal groups have courted Ahn to join the efforts to forge a new expanded party in preparation for the parliamentary and presidential elections set for April and December, respectively.

“He can be our standard-bearer in the next presidential election if he continues to maintain the high support rate,” said Moon Jae-in, former chief secretary to late President Roh, who has led the move toward merging opposition forces.

Gripped by a sense of crisis that their party may be trounced in next year’s elections, a group of reformative GNP lawmakers have called for drastic reform measures, with some suggesting Park create a new party, severing ties with President Lee.

New frame of politics

Political experts note the result of the Seoul mayoral by-election may be a prelude to an overhaul of the political landscape through the upcoming parliamentary and presidential polls, with the generational rift tearing down ideological confrontation and regional rivalry, which have framed Korean politics for the past decades since the military-backed authoritarian regime collapsed in 1987.

A major political front can be formed along the generational fault line for many years to come, the experts say.

An increasing number of voters born in the Seoul metropolitan area, which has held the key to parliamentary and presidential elections in the past, are free of regional bondages unlike their parents’ generation. Even considering that Seoul is relatively unaffected by regional rivalry, many observers note, the generational voting pattern has been clearly shown across the country in the recent elections. In the June 2010 election to choose the mayor of Busan, a traditional stronghold of the conservative GNP, a liberal opposition candidate won support from 63.1 percent of voters in their 20s, 61.4 percent in 30s and 53.5 percent in 40s, though he lost to the ruling party contender by a slight margin.

Analysts concede the concept of generation as a political variant is very fluid, affected by income, education and places of birth, and thus it is difficult for them to form a collective identity representing a structure of conflict. But they say the 2040 generation can be bound as such an identity group because they have accumulated similar experiences in growing through turbulent and difficult times.

For their part, those in their 50s or above also have a collective memory of contributing to fast economic growth, which professor Kim indicates led them to show a different attitude from the 2040 generation.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)