Efforts needed to transform national achievements into individual happiness

During a major forum on international aid in Busan last week, participants from around the world heaped praise on Korea for becoming the first country to transform from an aid recipient to a donor.

“Korea is symbolic,” said Brian Atwood, chair of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee. “It is a successful country. It is proof that it can happen.”

In his speech at the opening ceremony of the Fourth High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, President Lee Myung-bak reaffirmed Seoul’s pledge to double its official development assistance by 2015.

On Dec. 1 when the three-day forum closed, yet another statistic testifying to the country’s achievement came out. Korea shipped out $508.7 billion worth of goods in the first 11 months of this year, becoming the world’s eighth nation whose annual exports have exceeded the $500 billion mark, figures from the Knowledge Economy Ministry showed. In 1948 when its government was founded, Korea’s exports were just $19 million, less than half the figure for Cameroon and 0.3 percent of Britain’s shipments overseas.

It also surpassed $1 trillion in annual trade volume Monday, an achievement made by just eight other countries.

Korea saw its gross domestic product balloon from $3.9 billion in 1960 to $986.2 billion last year, ranking 15th in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund.

With its economic growth coupled with democratization since the late 1980s, Korea has elicited international admiration as the only country made independent after World War II to achieve both an advanced economy and democracy.

Korea’s accomplishments as a nation, however, have not translated well into individual happiness for its people. Intensifying competition and widening polarization have driven many Koreans into anxiety over their future, discontent with social conditions and even family tragedies, in some of which parents have fallen victim to their own children.

Experts say Korea will have established itself as a true model for other developing countries to follow when it succeeds in resolving a heap of problems accumulated through the development process.

Easterlin paradox

Multiple surveys have shown that life satisfaction felt by Koreans has remained at relatively low levels despite increases in their income and other achievements.

According to a recent report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on measuring well-being in its 34 member states, only 36 percent of Koreans felt satisfied with their lives, much lower than the OECD average of 59 percent.

About 62 percent reported having more positive experiences such as feelings of relaxation, pride in accomplishment and enjoyment in an average day than negative ones including pain, worry and sadness, compared with the OECD average of 72 percent.

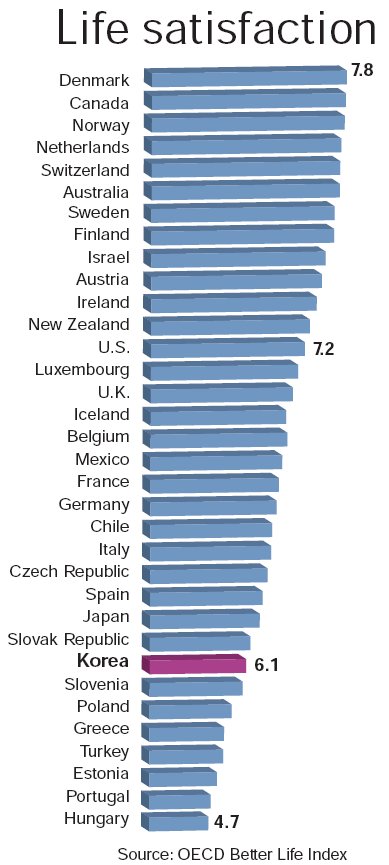

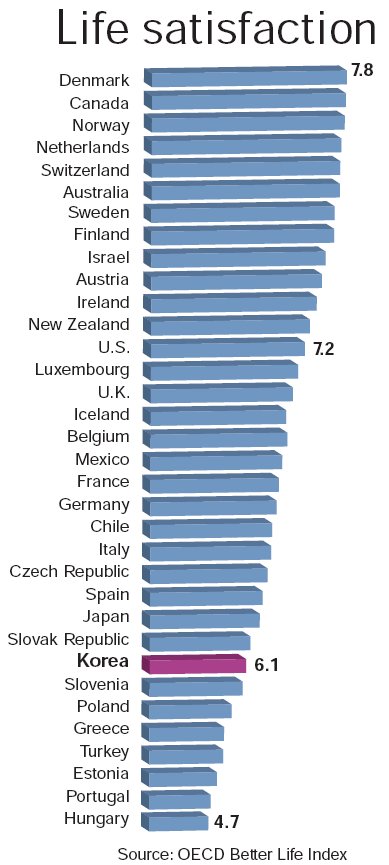

In the average self-evaluation of life satisfaction, one of the 11 topics in the OECD’s Better Life Index based on data from 2010, Korea ranked 25th with Japan, Slovakia and Slovenia at 6.1 on a scale of 0 to 10. Denmark topped the list with 7.8 while Hungary placed the lowest with 4.7. If the scores were recalibrated with Denmark given a perfect score of 10 and Hungary zero, Korea would score 4.5.

A report released by the state-run Korea Development Institute earlier this year put Korea’s quality of life at 27th among 39 countries belonging to the OECD and/or the Group of 20 in 2008, unchanged from the ranking in 2000. The country’s per capita gross national income increased from $10,841 to $19,296 over the cited period, according to statistics from the Bank of Korea. It is estimated to reach $24,000 this year, up from $20,759 in 2010.

Some analysts note that Korea has reached the phase of being subjected to the Easterlin paradox, put forward by U.S. economist Richard Easterlin in 1974. The paradox states that although people with higher incomes are more likely to report being happy, rising incomes do not necessarily lead to increases in subjective well-being.

The KDI report indicated Korea is in urgent need of working out a “development strategy that ensures a balance between growth and social integration.”

Rep. Sohn Hak-kyu, chairman of the main opposition Democratic Party, also mentioned the economic concept during a parliamentary session in September, urging Strategy and Finance Minister Bahk Jae-wan to shift the policy paradigm from growth to quality of life.

“Improvements in objective indicators do not seem to be much correlated with individuals’ subjective feelings in Korea,” said Kim Joong-baeck, professor of sociology at Kyung Hee University in Seoul.

“In a country like Korea, which has gone through a period of fast growth, many people are left without the accurate sense of their right status and thus likely to feel more deprived,” he said.

Uneasy conditions

The uneasy aspects of Koreans’ lives are reflected in the OECD’s index.

They work 2,256 hours a year, much higher than the OECD average of 1,739 hours and the highest rate among its member states. Koreans spend 55 minutes a day commuting to work, longer than the OECD average of 38 minutes, and devote 3.84 hours to leisure, compared with an average 4.31 hours among OECD members.

The average Korean home contains 1.3 rooms per person, less than the OECD average of 1.6 rooms per person. In terms of basic facilities, 7.5 percent of dwellings in Korea lack private access to indoor flushing toilets, much higher than the OECD average of 2.8 percent.

In Korea, 72 percent of people are satisfied with the quality of air, compared with the OECD average of 81.1 percent.

About 80 percent of Koreans believe they know someone they could rely on in a time of need, one of the lowest rates in the OECD where the average is 91 percent.

Only 41 percent of them say they trust their political institutions, one of the lowest rates in the OECD area. Nearly 65 percent of Koreans believe corruption has permeated their government, compared with the OECD average of 57.1 percent.

At 1.15 children per woman, Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the OECD. Together with Chile, Korea has the highest share (39 percent) of the adult population who are single and have never been married.

With less than 1 percent of GDP allocated to family benefits, Korea is the OECD member with the lowest public expenditure on them. Korea is advised by the OECD report to further develop its paid child care system to help working parents with the cost of young children.

The report praises Korea as an “exceptionally well-performing country in terms of the quality of its educational system.”

The average Korean student scored 539 out of 600 in reading skills, higher than the OECD average of 493 and the strongest performance among its members, according to the latest measuring by the Program for International Student Assessment. In Korea, 79 percent of adults aged 25-64 have earned the equivalent of a high-school diploma, higher than the OECD average of 73 percent. Among younger people ― a better indicator of a country’s future ― 98 percent of Koreans aged 25-34 have obtained the equivalent of a high-school degree, much higher than the OECD average of 80 percent and the highest in the OECD.

Koreans have notably put a high emphasis on the value of education, especially admission into a selected number of prestigious universities, which they believe will ensure success in life.

But the nation’s obsession with educational achievements has resulted in many family tragedies.

Days before the opening of the international aid forum in Busan, Koreans were shocked by a police announcement that a high school senior in Seoul killed his mother who was forcing him to become a “learning machine” and kept her body in their home for eight months.

|

A high school student arrested for murdering his mother re-enacts his crime at their home in Seoul on Nov. 25. (Yonhap News) |

The 18-year-old student said during questioning that he had murdered his mother out of fear that she would find he had fabricated his score on an exam during her planned visit to his school. The mother would hit her son with a golf club or a baseball bat, urging him to come first among all students nationwide in the college entrance exam, police quoted him as saying.

The boy’s father, separated from his wife for the past five years, reported his son’s suspicious behavior to police after his visit to their home last month.

Experts note the case, the latest in a series of domestic tragedies over the past years, illustrates the dissolution of families in Korean society as well as the severe fallout of the obsession with academic achievements.

They say that if the boy had not been left in such isolation that made his mother’s abusiveness all the more unbearable, their distorted relationship would not have led to matricide.

According to figures from Statistics Korea, two-person households accounted for 24.3 percent of the total last year, followed by single-member households with 23.9 percent, those with four members with 22.5 percent and those with three members with 21.3 percent.

Korean households are also under a rising debt burden, with household loans increasing from 797.4 trillion won ($700 billion) last year to 840.9 trillion won in September.

The average annual household income increased by 6.3 percent to slightly over 40 million won from 37 million won over the cited period, with its repayment of the principle and interest jumping by more than 22 percent to 6 million won from 4.8 million won.

“It is becoming really hard to make both ends meet with my salary,” said a 39-year-old company employee surnamed Kim, who borrowed more than 100 million won to buy an apartment early this year.

Emerging as a problem that may further threaten social stability is the retirement of 7.58 million baby boomers born between 1955 and 1963 over the coming years. A recent statistic showed only a quarter of baby-boomer households have minimum assets needed for their post-retirement life.

In a gloomy reflection of the distress weighing on Koreans, their suicide rate has remained the highest in the developed world since early 2000s. The number of suicides per 100,000 people reached 31 in Korea in 2009, compared to 24.4 in Japan and 21.5 in Hungary, which ranked second and third on the list of OECD members, according to figures compiled from data of the World Health Organization.

Indicator of hope

What may be hopeful for the country is that 60 percent of its people believe that their life will be satisfying in five years, representing nearly double the rate, according to the OECD report.

As part of cases backing such belief, local media have shed light on a retired wage worker who donated 100 million won to charity and a couple of female college students who returned a bag containing tens of millions of won to its owner.

“Building a society with a high degree of trust, in which people are assured that they receive due reward for what they have done, is one of the most important things for enhancing life satisfaction felt by individuals,” said Kim, the Kyung Hee University professor.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Health and care] Getting cancer young: Why cancer isn’t just an older person’s battle](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050043_0.jpg)