In the shadow of Mount Everest and its magnetic lore, a cross-border route with a grand name, the Great Himalaya Trail, is being touted as an epic, untapped alternative to the bucket-list trek to base camp on the world’s highest mountain.

Trekking this trail is an odyssey, not a routine vacation, and even promoters admit that it’s more a theory or consumer product for an untested market than a continuous path. Instead, it’s a web of paths, many unmapped and barely connecting, that meander east to west along the Himalayan range.

Granted, the Great Himalaya Trail lacks the history and utility of the Silk Road, the ancient trade network that linked Asia to Europe, or the cohesion and accessibility of the Appalachian Trail for hikers in the United States.

Instead, it is what trekkers and climbers make of it: a one-time hike through forests and grasslands at lower elevation, an assault on high passes that demand technical skill, or a periodic pilgrimage to sample chunks of the rugged expanse.

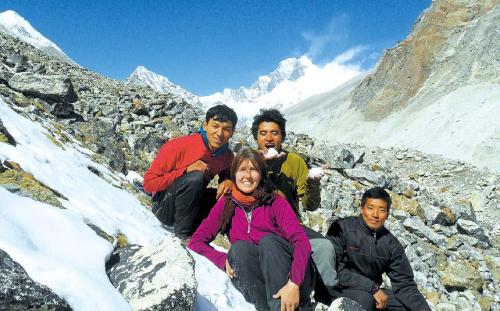

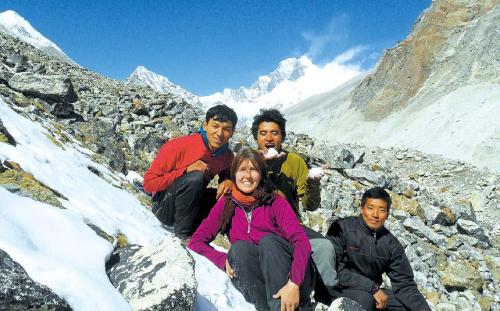

Susanne Stein, a 44-year-old German, completed an eastern trek on Nepal’s section of the trail with three guides in late 2011 and is preparing for the central and western leg in February. When it’s all over, she’ll have covered 1,050 miles (1,700 kilometers) in 165 days.

“One thing I like very much is just to move,’’ said Stein, a health specialist whose assignments for international aid groups have included Sudan’s Darfur region, Pakistan’s earthquake-hit Kashmir region, Afghanistan, and Nepal. “I always have the feeling I want to see around the corner. This keeps me going somehow.’’

Stein set out a week after a deadly earthquake in the Himalayan region. Some paths had been virtually wiped out by landslides, forcing her team to crawl at times. In the past, she visited the Everest region on her own. But Stein prefers guides on the Great Himalaya Trail, or GHT, because they motivate her when she is exhausted and they sometimes have to choose a way forward from several options.

“The GHT goes through areas where there is no guesthouse, no food, and no defined trail. So I guess for the average tourist, it is too difficult to do it alone. Besides the fact that you need to be fit. Probably for people with very good navigation skills, and a good map and GPS, it’s possible,’’ Stein wrote in an e-mail.

|

Trekker Susanne Stein (center), poses for a photograph with mountain guides during a Great Himalayan Trail hike in Nepal. In the shadow of Mount Everest and its magnetic lore, a cross-border route with a grand name, the Great Himalaya Trail, is being touted as an epic, untapped alternative to the bucket-list trek to base camp on the world‘s highest mountain. (AP-Yonhap News) |

A Nepal-based campaign aims to transform the Great Himalaya Trail into a basket of options for adventurers who prefer itineraries without roads and teahouses. It says western districts like Dolpa, Humla and Mugu offer rich scenery and local culture that has little outside exposure.

Promoters have broken the Nepalese stretch into 10 sections that can each be walked in a few weeks. Dorendra Niraula, an official at Nepal’s tourism ministry, hopes repeat visitors will trek parts of the trail over five or 10 years.

“We are in the initial stage of the project,’’ he said. “It’s a challenge. We are trying to diversify tourism.’’

The goal is for people to “go to places they have not thought of going,’’ said Robin Boustead, an Australia-based trekker who traversed 3,700 miles (6,000 kilometers) of Himalayan trails and says he has another 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) to go. He charted his trips with GPS, published a guide book and runs a trail website.

Boustead belongs to a loose alliance of trekkers, tourism agencies, non-governmental groups and Nepalese officials who hope a more even spread of tourist revenue can help a poor, politically weak nation that emerged from civil war five years ago.

These marketing pioneers are still finding their feet. Some efforts overlap; some agendas diverge. There are concerns about the commercial and environmental impact on areas unaccustomed to tourism.

Tourist-friendly Nepal spearheads the idea, and a trail section in Bhutan is on the map. There is less development in Chinese-ruled Tibet, as well as old foes India and Pakistan, which share the Himalayas. The goal of coordination across sensitive borders is immense, but Boustead wrote in an email that “the long-term strength of the GHT lies in its international focus.’’

About 600,000 tourists visited Nepal in 2010, according to government figures. The largest groups are from India and China, though Europeans, North Americans and Australians account for most trekkers. Well over 90 percent head for the Annapurna, Everest and Langtang regions, which offer tourist infrastructure.

“Access is definitely a real challenge and a difficulty that has to be worked on,’’ said Paul Stevens, a Kathmandu-based adviser for SNV, a Dutch non-governmental organization that provides funding and job training to communities on the Great Himalaya Trail. “Many of these places have air strips, but they’re quite hairy and you go in small aircraft and you wind through the mountains to get there.’’

The trail includes the Everest region, but highlighting remote parts is a hard sell. For some, reaching Everest base camp is among “things to do before you die,’’ said Dawa Steven Sherpa, a Nepali who reached the summit twice. In mid-January, he and Apa Sherpa, who has scaled Everest a record 21 times, plan to start a 120-day publicity trek across Nepal’s section of the Himalayas.

“The concept itself of walking along the whole length of the Himalayas is not new. What is new is making a package out of this that can actually be promoted for tourism,’’ Dawa Steven said. Until now, he said, Himalayan treks were viewed in a “very compartmentalized way’’ and the idea of “one trail to rule them all’’ was eclipsed by the fabled trails at the highest peaks.

In 1981, a team including Peter Hillary, son of Sir Edmund Hillary, who in 1953 led the first expedition to climb Everest, walked between two of the highest mountains, Kangchenjunga on the India-Nepal border and K2 in Pakistan.

Lizzy Hawker, a British endurance athlete, began to run the trail across Nepal in October, but quit after losing her bearings and gear.

“I temporarily lost the path between two villages and got in a bit of a tangle in a big dark forest of Himalayan proportions. Never lost but just needed to take my time to find the safe way down to the only bridge across the torrent below,’’ Hawker wrote in an online account. “The getting tangled part wouldn’t have mattered ― just lost time. But what did matter was losing my small sack with all the important things ― satellite phone, permits for my entire journey, solar panel, camera, money, compass, maps for that section etc.’’

Then there is Harald Six, an 18-year-old Belgian. In January 2013, he plans to walk from Istanbul to Pakistan, and pick up the Great Himalaya Trail. He wants to keep walking to Southeast Asia, partly motivated by concerns about poverty and climate change.

Six has a sleeping bag, water filter and GPS device, and hopes to save up 5,000 euros from work at an organic waste laboratory. He said his mother is supportive and his father sees the “seriousness’’ of his plan even though he would like his son to finish studying nature and landscape management at Ghent University.

“A lot of people want to see the world and so on, and they maybe, like, take a plane somewhere and do a world tour if they really are ambitious or are really set behind their plans. But then they see only those little spots of the world, flying from city to city,’’ said Six, who yearns to immerse himself in the mountains. “My interest in nature is too big to stay here.’’

By Christopher Torchia

(Associated Press )

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)