Anti-nuclear sentiment grows while government pushes for more reactors, bolsters safety

A string of breakdowns, aging reactors and aftereffects of the Fukushima meltdown have come together to trigger the biggest crisis in Korea’s nuclear industry since its birth.

With a parliamentary election less than three weeks away, some opposition candidates are joining forces to call for the scrapping of atomic energy plants. The intensifying political onslaught, emboldened by safety jitters among the public, poses further challenges to President Lee Myung-bak, who seeks to transform the country into a leading reactor exporter.

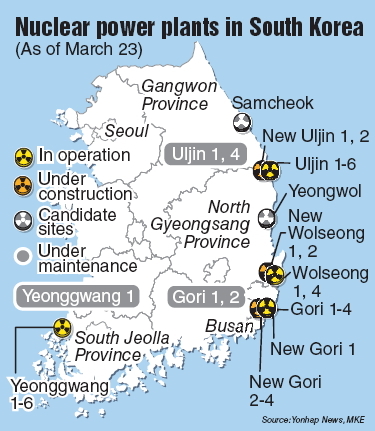

Against all odds, the government is pushing to boost nuclear energy to 59 percent of total electricity supplies by 2030 from some 30 percent now. It plans to add 19 to the existing 23 reactors, the second-largest power source after coal.

The 20-year roadmap is the centerpiece of Lee’s “low-carbon, green growth” initiative, which is aimed at powering the economy and creating jobs through investment in eco-friendly technologies and industries.

Experts say nuclear power is inevitable for a nation with scarce natural resources to keep its economy afloat. Korea, the world’s fifth-largest crude buyer, imports nearly all of its oil needs.

“We spend hundreds of billions of dollars a year to import oil and gas. Given the lower feasibility of other renewable resources, curbing the use of atomic energy will drastically increase imports and heap extra pressure on the national economy,” says Lee Heon-ju, a nuclear and energy engineering professor at Jeju National University.

History

Korea set up its first nuclear reactor at the peninsula’s southeastern tip of Gori, Busan, in 1978, to cater to spiraling electricity demand and trim energy imports.

The number of reactors has since shot up to 23 to date. Another three are currently under construction ― two in Busan and one in Wolseong, North Gyeongsang Province.

With five under regular maintenance, the nation’s aggregate capacity topped 20,600 megawatts as of March 21, International Atomic Energy Agency data shows. That makes Korea the world’s fifth-biggest nuclear power generator, trailing the U.S., France, Japan and Russia.

The capacity factor averaged 90.7 percent last year, far above the world average of 79 percent, according to Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co., the state-run nuclear plant operator.

Capacity factor is a gauge of the performance of a power generator as a ratio of its actual output over time to its full potential. A higher reading implies greater execution.

To better compete with leaders in international markets, the KHNP and KEPCO Engineering and Construction Co. teamed up to craft Korea’s own standard light-water reactor models with a bold investment package. They introduced the Optimized Pressurized Reactor 1000 in 1995 and its upgraded version, Advanced Pressurized Reactor 1400, in 2002.

In 2009, the United Arab Emirates chose to adopt four units of the APR 1400 for its first nuclear plant scheduled for 2020. The $20 billion contract saw Korea join the reactor exporter league alongside the U.S., France, Canada, Russia and Japan.

The landmark deal was inked by the Middle Eastern country’s Emirates Nuclear Energy Corp. and a consortium led by Korea Electric Power Corp., the state-run electricity grid operator. It also entails an additional $20 billion order for operation and maintenance for 60 years.

“We were impressed with the KEPCO team’s world-class safety performance, and its demonstrated ability to meet the UAE program goals,” ENEC chief executive Mohamed Al Hammadi said upon the signing of the deal.

Although a relative newcomer to the global atomic power scene, Korea has earned credit for its safety, cost-effectiveness, technological know-how and quick construction.

Since 1978, the country’s 23 reactors have not had any major accident.

“Thanks to an active national program of nuclear power plant construction, Korea has developed distinct competitive advantages in terms of low cost, high credibility and high performance,” said Michel Berthelemy and Francois Leveque of Mines ParisTech, a France-based engineering school, in a 2010 report.

“At the same time, due to the important barriers to enter the nuclear export market in the UAE, Korea has had to sacrifice its profit margin and has benefited from strong political support from its government through export financing.”

No more nuclear renaissance?

That government backing, however, as well as the coveted safety record, is teetering on the edge of a political abyss.

The Lee administration has been under pressure since the disclosure of KHNP officials’ recent cover-up of a 12-minute blackout at the Gori-1 unit, the oldest reactor here. Neither damage nor radiation leakage occurred but the incident set off a slew of rallies among residents fearing a more serious accident as Japan suffered last year.

|

The landscape of New Gori-1 and 2 in Gijang, Busan (KHNP) |

The incident came on the heels of 11 breakdowns of reactors last year, which fanned concerns about power shortages that resulted in a nationwide rolling blackout in September.

In a poll released on March 6, more than six out of 10 Koreans were against the government’s nuclear energy policy. Almost 80 percent of 1,100 respondents said they oppose lengthening old reactors’ lifespan. These proportions are notably higher on a national scale than at any other point in decades.

Hitching onto the deepening anti-nuclear sentiment, opposition lawmakers are stepping up their attacks on the unpopular president and his ruling Saenuri Party, vowing to phase out nuclear energy should they seize power in the April 11 vote.

“The Fukushima disaster sent a frightening ultimatum to mankind,” Han Myeong-sook, the main opposition Democratic United Party’s leader, told senior journalists on March 12.

“We should abolish atomic power in stages and invest in other renewable sources on a national level. That will create safe and more jobs and technologies.”

Reality check

Many experts see Han’s vision as out of reach, owing to the relatively lower outputs of solar, wind or any other kind of “clean” energy.

“Reassessing the system is one thing, but getting confused over its role is another,” said Chang Soon-heung, president of the Korean Nuclear Society and a professor at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in Daejeon.

“However we try, we can’t raise the share of solar power of Korea’s electricity from the meager 0.1 percent now to that of nuclear energy anytime soon. Demand will also go up further given brisk economic activities.”

A solar power station must be as large as 66 million square meters to produce the equivalent amount of electricity from merely one nuclear reactor, according to Lee of JNU. This makes solar energy highly uncompetitive at a commercial level in a small country like Korea, he says.

While warning of political abuse of energy security issues, Seoul National University’s Hwang Il-soon stresses safety as a priority.

“We need to overhaul everything from hardware to software to governance,” said Hwang, a nuclear specialist.

Since the Fukushima debacle, the government has outlined far-reaching safety tests and contingency schemes at existing stations, while notching up earthquake resistance standards for forthcoming ones.

It also wrote 50 short- and long-term action plans based on worst-case scenarios covering an extreme natural disaster, power failure and severe accident, to which the International Atomic Energy Agency recently gave a positive review.

With the Nuclear Security Summit in Seoul drawing near, the government is rushing to reassure Koreans of the safety and the need for atomic plants.

Knowledge Economy Minister Hong Suk-woo and other involved officials are visiting Busan on Friday to meet with the city’s mayor, council members and residents in a bid to relieve their anxiety.

“People’s safety is 100 times, 1,000 times more important than a couple more export deals,” Hwang of SNU said.

“Ethics is pivotal in atomic power ― state-of-the-art technology without ethics is of no use.”

By Shin Hyon-hee (

heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)