Some big titles are used to describe artist Kim Whanki. The artist is called a “pioneer of abstract art,” for adopting simplified compositions in his paintings, and the “Korean Picasso” for his prolific creation of more than 3,000 works.

He is also a best-selling artist in the contemporary art market. One of his earlier works, a painting called “Moon and Plum Blossom,” sold for $663,750, almost double its estimate of $350,000-$400,000, at the Japanese and Korean art auction at Christie’s in New York on March 20.

|

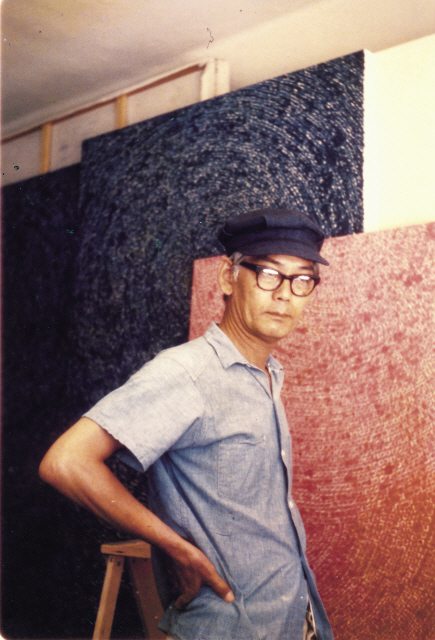

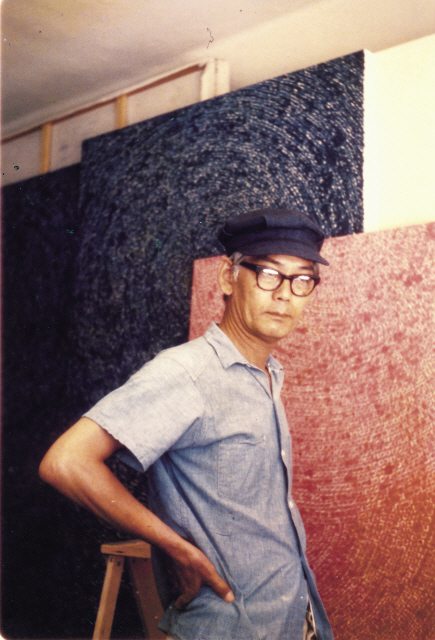

Kim Whanki in his studio in New York, 1971 (Whanki Museum) |

But few remember him as an artist who sought to devote himself to discovering Korean aesthetics and kept challenging his artistic level. Or a great educator and a poet who left a significant impact on his art students.

“He was a very talented man who worked simultaneously as an artist, educator and a poet,” said Lee Tae-hyun, one of Kim’s students, who said Kim still has a great deal of influence on his own artistic practice.

Kim taught at the art college of Hongik University from 1961-63 before he moved to New York in an attempt to challenge his artistic boundaries.

Suk Ran-hi, an established artist in Korea who was in a drawing class with Lee, recalled Kim as a teacher who helped his students find answers to the fundamental questions.

“Why do we paint? Why do we practice art? Kim helped us find answers to those questions,” said Suk at a reception Friday for “The Centennial Celebration of Kim Whanki’s Birth: Where, What Have We Become and Meet Again,” a Whanki Museum exhibition that celebrates what would have been Kim’s 100th birthday.

“His office was always open. When I got stuck in my project, I visited him and had a moment with him and then I continued my work,” recalled Suk.

“Also, I’ve never seen another Korean artist as tall as 180 centimeters,” Lee said, referring to his teacher’s stature.

Whanki Museum, established in 1992 by the Whanki Foundation and Kim’s wife Kim Hyangan in Buam-dong, Seoul, is currently holding a special exhibition that chronicles the life and legacy of the artist. About 70 artworks, including the most representative paintings, drawings and objects, reconnect the viewers with the artist who died 39 years ago.

Each section of the exhibition is named after a place the artist stayed during his lifetime.

The Seoul/Tokyo (1913-1937) section is an archive of Kim’s earlier life and works. Paintings including the printed images of his debut work “When the Larks Sing” from 1935 and “House” from 1936 show the earlier forms of his abstract art.

The “Rondo” painting occupies a meaningful place in Korean modern art history as it is registered as a cultural asset by the Cultural Heritage Administration in recognition of its dynamic composition represented in curving color blocks with silhouettes of figures and a piano.

The exhibition also shows his obsession with white porcelain and wooden craftworks, which filled every empty space of his house in Seongbuk-dong, Seoul, and were buried in a well in the front yard to save them from damage during the Korean War.

|

“Jar and Plum Blossom,” 1957 (Whanki Museum) |

“His house was full of white porcelain and antique wooden furniture. When he had a block while painting, he would touch a jar and that would help him ‘unlock’ and continue his painting,” said Park Jeong-eun, curator of Whanki Museum. Other natural motifs he frequently used were plum blossoms, mountains, deer and the color of the sea in his hometown.

Kim continued to draw during the Korean War and some of the drawings offer a glimpse of life during the conflict.

His favorite subjects continued to appear in his works completed during the Paris years (1956-1959). He chose the city in order to overcome the isolation of practicing art in Korea. In the French capital, Kim’s works were praised as having “poetic sentiments of Korea.” Kim was finally introduced for the first time at the 1963 Sao Paulo Biennale and Paris Young Artists Biennale.

The New York period from 1963 marks an important transitional period for Kim as his usual natural motifs began to disappear and more simplified forms such as dots, lines and planes became the dominant features of his paintings.

The artist’s life in New York wasn’t always happy as he received unfavorable reviews and suffered financial difficulties. He once lost a group of paintings displayed in his solo exhibition and on another occasion was deceived by a gallery owner who sold his paintings without paying him.

The artist, who lived within a tight budget, made collages out of colored paper and painted on the pages of the New York Times newspaper.

Despite the difficulties, Kim left behind several masterpieces featuring dots, lines and planes, including the famous “Where and in What Form are We to Meet Again?” series and “Universe.”

Although blue, the color of the sea in his hometown of Sinan, South Jeolla Province, dominated his paintings, the last painting of the exhibition is in black, a color choice that indicates his deteriorating health due to the intensive labor involved in drawing 100,000 dots.

The unfinished work still has pencil lines he couldn’t erase. He died of a brain hemorrhage in 1974 in New York.

Kim’s paintings are also on view at the nation’s largest portal website Naver. The Whanki Museum and Naver signed an MOU to make the artworks more accessible to a wider audience in celebration of the 100th birthday of the artist.

The paintings are on view at http://arts.search.naver.com.

The centennial exhibition runs through June 9 at Whanki Museum, Buam-dong, Seoul.

For more information, call (02) 391-7701.

By Lee Woo-young (

wylee@herladcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)