Atlanta poet Collin Kelley was at a London gallery in 2010, taking in a retrospective of photographer Sally Mann, when he was gobsmacked by something in the Virginia-born artist’s otherworldly, black-and-white images. He saw eerie parallels to his own work ― the poetry he’d set aside years earlier to focus on writing fiction.

He had a collection of poems that had been “kind of floating around” since 2008, enough for a book. He’d given it a couple of titles, combined different poems, changed the sequencing. “But it just never jelled like I wanted it to,” he says.

Unable to shuffle the parts into place, he put it on the back burner and went on to other things. He signed a contract to write a trilogy of novels about murder and international intrigue for Vanilla Heart Publishing, and dove from one straight into the next.

|

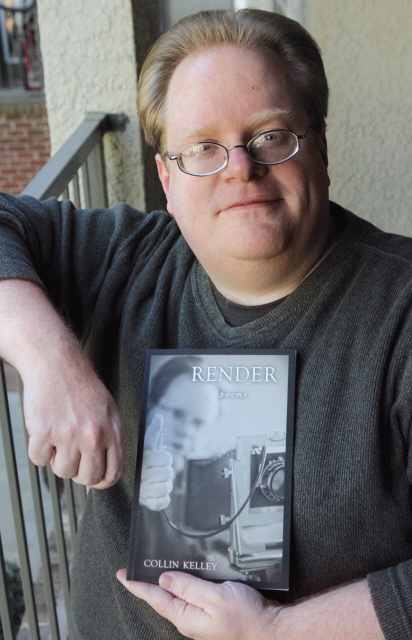

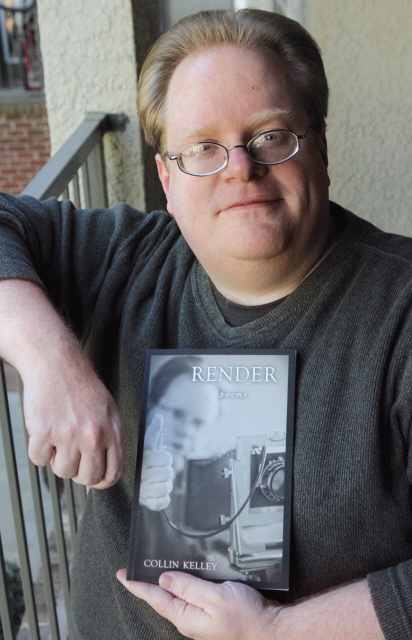

Poet Collin Kelley, who is coming out with a new book, “Render,” poses for a portrait at his Atlanta home, on Feb. 27. (Atlanta Journal-Constitution/MCT) |

Kelley is a familiar face in Atlanta’s literary scene. He won a 2007 Georgia Author of the Year award, along with co-editor Kodac Harrison, for “Java Monkey Speaks: An Anthology.” And last year his novel, “Remain in Light,” was a finalist for the Townsend Prize.

He sits on the board of Poetry Atlanta and on the advisory council for Georgia Center for the Book, where he curates and hosts a regular poetry series.

He’s co-director of the Atlanta Queer Literary Festival, and he’s a frequent presenter at poetry readings around town, across the country and in the U.K.

It was during one of those trips as a guest lecturer that Kelley heard about the Mann exhibit, which included her iconic photographs of her children, Civil War battlefields and the Body Farm, a research facility at the University of Tennessee where human bodies are allowed to decompose in the open air for the sake of science.

Inspired, Kelley came home and wrote “Render,” an homage to Mann’s imagery and process.

“As I was writing that poem and the stanzas that catalog her body of work, something kind of clicked in my head, and I was like, You know what? I’ve kind of written about all of this stuff, in a way. And so I went back and started looking at the poems again.”

He discovered some unexpected coincidences.

“There’s a reference to Sally Mann that I’d totally forgotten about, in my poem ‘Tuscumbia, Alabama.’ And then there was the reference to the Body Farm in the Knoxville poem that I’d written, and several references to visiting Civil War battlefields when I was a kid with my parents.”

The parallels suggested a structure, the idea of “a book of photographs in poetry.” With that as a framework, Kelley found his “entry point.”

This month, Sibling Rivalry Press will publish Kelley’s second full-length book of poetry, “Render.” Like Mann’s photographs, Kelley’s poems concentrate on family, adolescence and pieces of the Southern landscape. Kelley’s shutter opens to moments when the real world interrupts the ideal, when ― with a “sharp crack of bones” ― suburban dreams break apart. His flash reveals the hidden junctures of coming of age and coming out, sexual arrivals and revelations, the secret deliverance found in pop culture and its rich iconography.

And like Mann’s often mysterious landscapes, the poems leave as much unsaid as they reveal. In “Knoxville: Summer, 1982,” Kelley juxtaposes the disappointing wonders of a World’s Fair with a family’s uncertain future and a teen’s shifting sexuality:

“That night I dream ...

a Magic 8 Ball in my hand

I shake it hard, but the same message

always floats to the surface:

better not tell you now.”

Kelley’s voice ― brash, tender, angry, nostalgic, sexy ― is one that now understands and even welcomes the “imperfections and subtle debris” of life.

It’s a voice well equipped to fight a host of demons ― of reaching back to rescue his younger self from “the coming storm” he writes about in many of his poems. But he didn’t find it overnight. When Kelley first started writing poetry in high school, he says, “I felt like I was kind of mimicking Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, who were two of my favorites.”

The budding poet discovered Sexton in 1986 while listening to the Peter Gabriel song “Mercy Street,” which takes its title from Sexton’s last book, “45 Mercy St.,” published posthumously.

Suicidal, confessional, bipolar Sexton became Kelley’s “touchstone,” but he continued to read widely, both classic and contemporary poetry ― Edna St. Vincent Millay, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Walt Whitman, Rilke ― searching for his own voice.

After his first poem was published in 1993, another decade would pass as he worked through his many influences. “I didn’t want to just write more Anne Sexton poems,” he says with a wry laugh. “You can’t top Anne Sexton.” In the meantime, Kelley established a career in journalism, starting out at the Fayetteville Sun at age 16, moving on to the Marietta Daily Journal and ending up at Atlanta Intown, where he is managing editor.

By 2003, Kelley felt he had matured enough as a poet to self-publish his first full-length collection of poems, “Better to Travel.” Two chapbooks followed, “Slow to Burn” and “After the Poison,” as well as two plays and his novel trilogy, the last volume of which comes out next year.

Many of the poems in “Render” will be familiar to anyone who’s spent time at local poetry readings and open mics ― Kelley has performed them frequently over the years. “Wonder Woman,” in particular, is a favorite, Kelley says, as is the “The Virgin Mary Who Appears in a Highway Underpass (“popping up where you least expect her / causing trouble for the locals”) and the cocky “Why I Want to Be Pam Grier.”

“I want to be an idol, a nobody,

a ‘whatever happened to her,’

then put on my Kangol hat, my tight black suit,

look better than I did twenty years ago,

and smoke you one more time good and proper.”

If anyone were giving out awards for good stewardship of the literary community, Kelley would get a few. His name frequently is attached to poetry events throughout the city, including several taking place in April, deemed National Poetry Month by the Academy of American Poets.

“I feel like if I’m going to do it, I want to help other people do it, too,” he says. “I want to go out and hear good poetry. And I want to provide opportunities for people who are doing it. If you want to be heard, you have to listen.” Musician and spoken word artist Kodac Harrison, who hosts a weekly spoken word event at Java Monkey in Decatur, calls Kelley “one of the hardest workers” in the Atlanta literary community and credits him for attracting new voices to the poetry scene.

William Starr, executive director of Georgia Center for the Book, agrees, calling Kelley a “supportive and encouraging spirit.” But to Kelley, it’s just another day in the life of a poet.

“Poetry is still the tiniest of the smallest little niche of American literature, it’s this tiny little speck in the spectrum,” he says. “You’re not going to make a living off poetry. So you do it for the love. You do it for the art. Which is a cliche, but it’s true. There’s a calling.” (MCT Information Services)

By Gina Webb

(The Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)