<관련 영문 기사>

‘Diplomacy, reconciliation, only way to handle N. Korea’

By Song Sang-ho

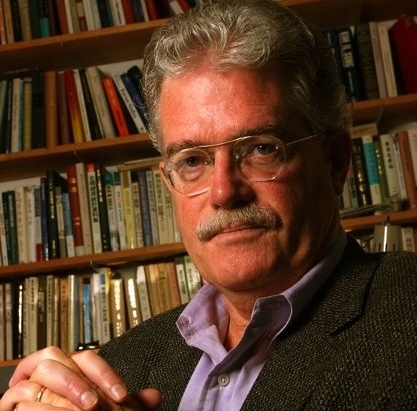

Bruce Cumings, a leading U.S. scholar on Korea’s modern history, said diplomacy and reconciliation was the “only answer” to how to handle North Korea’s nuclear adventurism.

During an interview with The Korea Herald, the historian at the University of Chicago also criticized former President George W. Bush’s hard-line policy as the “major cause” of the current security dilemma posed by Pyongyang’s nuclear armament.

“It (the North) cannot defeat any of its near neighbors, but at the same time, it is still very hard to see how any invading army could defeat the North and occupy and govern it, without tremendous loss of life and fearsome consequences,” he said.

“So the only answer is diplomacy, reconciliation and avoiding specious and premature triumphalism.”

Labeled a “revisionist” historian, Cumings has been attacked by South Korean conservatives for challenging the traditional view of the Korean War: communists were to blame for the 1950-53 conflict.

He expressed frustration, denying that he ever said the South started the conflict.

“Supporters of the (Chun Doo-hwan) regime in and outside the government were running around trying to discredit my work by saying ‘Cumings says the South started the war!’ I don’t know how may times I heard this including demands that I apologize for saying it,” he said.

“But it is hard to apologize for something one never said.”

Following are excerpts of the interview with Cumings. The full transcript is available on the Korea Herald website.

Korea Herald: This year marks the 60th anniversary of the armistice agreement. Can you comment on the armistice agreement -- its meaning, traits, role and past, current and future challenges?

Cumings: This was a most unusual armistice agreement because unlike, say, the end of the fighting in World War I, it was not followed by a peace conference and treaty. Thus it has been the sole legal guarantor of the curious state of no war and no peace between the belligerents for the past six decades. That one of the belligerents never signed it (the Republic of Korea) also made it an unusual way to call a halt to the fighting.

Also strange was the ostensible peace conference, held in Geneva in 1954, where the communist and non-communist sides came to important agreements that ended the first Indochina war (and divided Vietnam politically), but got nowhere on a peace treaty for Korea. After learning in the State Department archives that the U.S. expected nothing to happen at Geneva (in part because the Americans thought the communists would try to get at the diplomatic table what they could not get on the battlefield), in an interview I asked U. Alexis Johnson, who was on the U.S. delegation, how one prepares for a conference where nothing is going to happen. “Oh,” he responded, “you make your speeches and you also try to make sure that Korean Foreign Minister P’yon is well established and knows what he’s supposed to do and ... you don’t let Syngman Rhee sabotage it.”

I doubt that anyone at the time thought the armistice would still be the main guarantor of peace in Korea some 60 years later, but without a final peace treaty or agreement it is still a weak reed. When former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta can say, as he did in the spring of 2012, that we have been “within an inch of war” with North Korea for weeks and months, that is both an admission of a colossal failure in American policy, and of the fundamental weakness of the armistice. It halted a hot war, but certainly did not end it.

KH: Your analysis of the cause of the Korean War has triggered much controversy. Can you again explain your understanding of the cause and characteristics of the war for our readers?

Cumings: The human problem is that people do not read deeply researched books, which mostly appeal to professional scholars, but nonetheless they like to run around acting as if they did -- and gossiping about what they think is contained in such books. I did not write about the opening of conventional war in June 1950 until 1990, when the second volume of my Origins of the Korean War appeared. Yet by the mid-1980s, after the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship had banned my first volume (which appeared in 1981), supporters of that despicable regime, in and outside the government, were running around trying to discredit my work by saying “Cumings says the South started the war!” I don’t know how many times I heard this -- including demands that I apologize for saying it.

I wrote 33 chapters on the origins of this war, and only one was titled “Who Started the Korean War?” There I presented several scenarios for how the war might have started, based on the existing documentation at the time, with the whole point of the chapter being to deconstruct the idea that the war “started” in June 1950. The theme of both my volumes was that the essential conflict began in the 1930s, between Korean forces resisting the Japanese and Korean forces serving the Japanese, between people who supported a very oppressive land system and those who did not, etc., a conflict that was vastly accelerated by events that occurred from 1945 to 1950.

By 1949, the militants who knew how to use the weapons of war were arrayed on either side of the 38th parallel, with the U.S. having put in place and supported former Japanese army officers like Kim Sok-won (who commanded the parallel during the summer and early fall of 1949), and the Russians and Chinese backing militants who had fought the Japanese going back at least to 1932. Here was a perfect recipe for civil war.

To understand June 1950 one needs to understand the border fighting along the parallel that was begun by South Korean forces in May 1949, and which continued until December 1949 -- the North Koreans initiated much fighting, of course, but according to secret reports by the U.S. commander on the scene, Gen. Roberts, the majority of the fighting was started by the southern side. A real crisis came in August 1949, when the North attacked a hilltop emplacement north of the 38th parallel that was occupied by southern troops, and quickly routed them -- to the point that the Ongjin Peninsula, south of Haeju, seemed about to fall to northern forces. Syngman Rhee wanted to counter that by attacking Cheorwon, north of the parallel. U.S. Ambassador (John J.) Muccio restrained him, worried that a war would break out; at virtually the same time, Kim Il-sung was restrained by the Soviet ambassador from widening the conflict into what the ambassador called a civil war.

KH: What do you think about the implications of the Korean War? Ideological division that seems to be insurmountable could be one example of its impact on Korean society.

Cumings: Well, in the post-Cold War era Koreans made great progress at overcoming the ideological divisions, at least from 1998 to 2008 under Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. Any person under 60 cannot have experienced the terrible struggles that divided Koreans from 1945 to 1953, and this simple human fact is a problem for all the hard-liners and warmongers on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone. Young people do not have -- and really cannot have -- the visceral hatreds and grudges that kept Korea divided for so long, and so they are the greatest hope for finally overcoming the national division.

A little-noted aspect of the Korean War is the way in which it set up a sharp competition for development between the South and the North. The North won this race for about 25 years after the armistice, and the South has won it ever since. With firm big-power backing during the Cold War, both sides were recipients of huge amounts of foreign aid (although the South got much more than the North), and both became avatars of Third World development — the North primarily in the ’60s, and the South in the ’70s and ’80s. Once the North Korean economy is rebuilt on a more contemporary basis, and if the two Koreas can ever be reunited, a real economic powerhouse will be in place.

KH: North Korea has conducted nuclear tests three times and it claims that it is already a nuclear-armed state. Do you think Pyongyang will ever renounce its nuclear ambitions?

Cumings: This renunciation would happen only under very tight guarantees that the U.S. would not threaten it with nuclear weapons, and only if others do not try to roll back the clock on the North’s nuclear programs. After what has transpired in recent years, with both the U.S. and the South dramatically reversing their stances of engagement toward the North, I think any general in Pyongyang would want to maintain ambiguity about how many nuclear weapons they might possess, and how effective their medium- and long-range missiles might be. Through negotiations the North can probably be brought to a point of “useless ambiguity,” that is, they get to keep a few nukes to make them feel secure (outsiders could never find them all anyway), but which cannot be used against others without a holocaust descending on the North; meanwhile the other diplomatic parties would achieve a cap on further production of plutonium, highly-enriched uranium, and long-range missiles.

Given how far things have come since 2002, I don’t see how this can occur without the U.S. pledging a “no-first-use” policy on its own nukes, while making much more serious attempts to reduce the thousands of nuclear weapons in its own arsenal. Unfortunately, that seems about as likely as the North giving up its nukes. But a cap on the North’s programs is much better than President Obama’s policy of “strategic patience,” which isn’t a strategy but it is very patient -- patient enough to stand by and watch the North develop a fully-usable nuclear arsenal, with attendant consequences for the Northeast Asian region.

KH: There has been much talk about the possible collapse of the reclusive regime in Pyongyang. But there has not been much talk of reunification. What do you think about the possibility of reunification and what kinds of efforts do you think should be made in preparation for it?

Cumings: I have said and written since the Berlin Wall fell that whoever anticipates or expects or seeks to impose a collapse of the North will be likely to find themselves in the second Korean War. But to the contrary, we have had almost a quarter-century of drivel on “the coming collapse of North Korea.” This even became the policy of the Clinton administration in the mid-1990s, until William Perry and others, with much help from Kim Dae-jung, came to understand that the North was not going to collapse, so it had to be dealt with “as it is, not as we would like it to be.” At the time this phrase struck me as a bolt out of the blue, a sudden glimmer of American sobriety amid a host of ignorant, failed and useless assumptions about the North going back to 1945. This was the peculiar, unexpected, enhanced clarity at the basis of the 2000 missile agreement and the engagement toward normalized relations that should have succeeded it.

The problem in understanding the North and grasping its behavior is hardly ever at the level of facts or daily events or episodes that come and go -- or about which Kim runs the country. It is at the level of scraping our own assumptions to the bone, to try and figure out a place that one may hate and revile, but that specializes in difference from beliefs that we hold dear, that will not do what we want them to do, and that persists no matter how many times we huff and we puff and try to blow their house down.

As to preparations for unification... my own view is that no unification will occur in the next few decades without prolonged efforts at engaging the northern leadership, pursuing sincere reconciliation, treating northerners fairly, and respecting their human dignity and their history.

KH: What frustrates Koreans is the stark reality that reunification is not something Koreans can realize alone given that it is an international issue. What do you think?

Cumings: At the risk of harping on the events of 2000, U.S. support for the missile deal and for President Kim’s efforts at reconciliation, the June summit, etc., was predicated on the U.S. being the guarantor and the facilitator of reconciliation and eventual reunification. Kim Jong-il agreed at the summit that American troops could remain in the South for the foreseeable future, so long as they stayed in the South. He was fearful of Korea’s geostrategic position, with China and Japan both being strong at the same time, for the first time in modern history. The U.S. would thus emerge as the closest ally of a unified Korea, able thereby to balance Japan, China and Russia while maintaining its commitments to Korea and the security architecture that it had built in the region since 1945. This was a matter of bringing the North into that system, as a neutral or innocuous party for some time to come.

This plan would not place South Korean or American troops on the Chinese border after reunification, something Beijing fears, and Korean reconciliation would not come at the expense of any of its neighbors. As a Korean strategy, this idea can be seen as early as the 1880s: to remain friendly with Korea’s neighbors, but to ally with the U.S., which has the virtue of being across the vast Pacific -- and thus less attentive.

China is much stronger in 2013 than it was in 2000, and may demand to be a central part of any Korean reunification. As for Japan, it will do what the U.S. tells it to do, as it has since 1945 (when dealing with major issues). Russia is not strong enough in the region to oppose such an outcome.

Ultimately, Korea is for the Koreans. It always has been, until the past century -- for millennia, Koreans have been the well recognized people who live on the peninsula below the Yalu and Tumen rivers. Since 1953 Koreans have imposed upon themselves (with much foreign help) a division system that, as Dr. Paik Nak-chung has shown in his work, systematically works against unification. I think the record of the past 100 years shows that if Koreans don’t care about their own interests, we can be sure no one else will. If their interest is truly unification, they can surely accomplish it with their own hands.

(

sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)