Seok Gwang-soo, a 40-year-old single father living in Pohang, North Gyeongsang Province, often feels as if he is forced to neglect his own children.

Two years ago, the divorced father of three was diagnosed with cerebellar ataxia, a rare brain disease with no effective treatment.

Unable to move and work and with no viable help from his families, he relied on government-certified nannies to take care of his kids -― aged 10, 7 and 5 ― in the evenings and on weekends when they are out of school and a state-run day care center.

But things have gotten much more difficult for Seok this year as the Gender Ministry cut its budget for the child care program by 458 million won ($418,360).

With the cut, families with children aged 3 months to 12 years can now utilize the service for a maximum of 480 hours a year, compared to the previous 720. This means a daily nanny can only stay for an hour and 33 minutes a day.

“I need nannies to come in every day because of my medical condition,” Seok told The Korea Herald.

“But after the budget cuts, my nanny can only stay for less than two hours a day ― which is devastating. The weekends are the worst ... They are just at home with me, but I literally cannot do anything for them.”

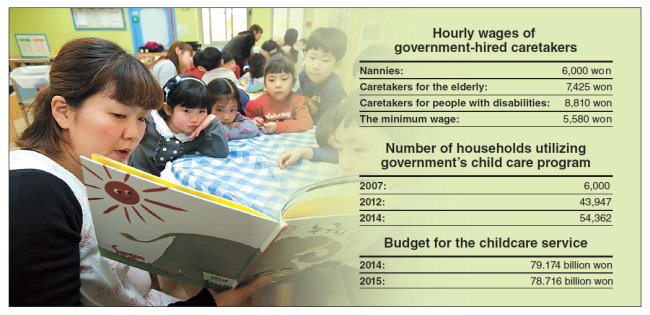

Since the Gender Equality Ministry established the program in 2007, the number of households who use the service increased dramatically from 6,000 to 54,362 in 2013.

This year’s budget cut is expected to deal a blow to such households as well as nannies hired by the government for the service.

For Jeong Seoum-gyul, a 36-year-old working mother in Daegu, the limited hours of the program have turned into a financial burden.

The part-time school teacher who also works at a car washing service had been relying on nannies to take care of her 29-month-old daughter.

While the daughter stayed at a day care center, nannies were Jeong’s only resort when she worked from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m. at a car wash with her husband every morning.

Now, because of the limited hours of the service, Jeong feels she is only left with terrible options.

“I either have to quit my job at the car wash or hire a nanny from a private company to take care of my daughter starting at 4 a.m., though I don’t know if any nanny (from a private company) would be even willing to work at 4 a.m.,” Jeong told The Korea Herald.

“Either way, I would have to spend at least about 600,000 won ($533) more every month. For people like us who have to make ends meet, that’s not a small cost,” Jeong said.

What disturbs Jeong most, she said, is that the government decided to cut back the program without warning.

“I wish they at least had told me in advance so I could have planned ahead,” Jeong said.

“They told us the decision very abruptly without offering any alternative options for us. It feels almost as if I’ve been conned by the government.”

The ministry explains that the latest budget cut was due to “overlapping” child care programs offered by other ministries. The Education Ministry, for instance, offers an after-school child care service where schools look after children of working parents after classes are over. The Welfare Ministry, for its part, provides special child care services for babies aged from 6 to 36 months.

“Parents still tend to prefer having nannies take care of their children at their homes instead of placing the children at day care centers,” Gender Minister Kim Hee-jung had said in last year’s National Assembly meeting. She criticized the Strategy and Finance Ministry for citing similar programs as a way to downsize the budget.

The Gender Ministry said it would continue to seek ways to expand the program.

“We acknowledge that some may find the things (resulting from the budget cuts) difficult,” said Song Young-gwang from the ministry. “We’ll continue to have discussions to tackle the issues.”

Meanwhile, the government’s budget curtailment is also affecting the nannies, who have already been struggling with low wages, weak job security and the government’s unilateral decisions on employment terms. As of February 2014, a total of 13,889 have been hired by the government for the child care service.

Among many welfare workers hired by the government, nannies working for the child care program earn the lowest wages ― 6,000 won ($5.30) an hour. Those who care for the elderly earn 7,425 won, while those who work for people with disabilities make 8,810 won.

Although the government raised the nannies’ hourly wage from 5,500 won to 6,000 won this year, the workers were informed in September that they would no longer receive extra stipends for transportation. Up until September, the workers were given 1,000 won to 1,500 won per commute.

Lee Kyung-seon, a nanny based in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province, now spends about 100,000 won additionally every month because she no longer receives the transportation allowance.

“I make 12,000 won to care for a child for two hours, and I spend 4,000 won on transportation. So in the end, I am only making 4,000 won an hour, which is lower than the minimum wage ― 5,580 won,” she told The Korea Herald.

Observers said the government’s decision overlooks the Labor Law, which states in Article 94 that an employer must consult with the majority of workers when amending rules of employment, and seek their consent if the rules are to be modified unfavorably for workers.

The workers say the Gender Ministry informed them of the cut via text message.

“Transportation cost is just one of many problems,” said labor attorney Kim Min-cheol. “The nannies must be given a total of 15 days of vacation every year by law. If they don’t get these days off, they should be paid extra. But I know many nannies who didn’t know the vacation time even existed.

“The government as an employer cannot go against the nation’s labor law,” he added. “This should be fixed.”

Kwon, a nanny in Gwangju, said she only learned about the country’s Labor Standards Act last year, after almost eight years of working as a government-certified caretaker. After the transportation allowance cut, she commutes by walking, which takes about 40 minutes each way.

“It was extremely shocking and disillusioning to find out that the government, not even a private company, does not follow the labor law.”

The government has been stepping up efforts in recent years to provide a better welfare and support system for mothers nationwide, in an effort to fight the declining birthrate and aging society.

Despite President Park Geun-hye’s renewed emphasis in February on the need to tackle the population crisis, parents say they still suffer from inconsistent policies that fail to fully reflect reality.

Korea’s birthrate stood at 1.18 child per woman last year ― the lowest in the OECD. An inadequate number of state-run child care facilities as well as poor work-life balance for double-income married couples have been considered some of the key contributing factors.

The government predicts that the nation’s military would be short of 84,000 soldiers by 2030, and almost half of the entire population will be 65 or older by 2100 at the current birthrate.

Jeong, the working mother in Daegu, said she and her husband recently decided against expanding their family.

“It seems like having a second child is a privilege for those who have money and resources,” she said.

By Claire Lee (

dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)