Crossing the Hangang River in Seoul on the way to work every morning, 29-year-old office worker Kim Soo-hyun used to enjoy gazing at the vast waterway bordered by panoramic stripes of apartment buildings and skyscrapers.

Although the view is often photo-worthy, the experience has become less and less pleasant in recent years, as a thick smog of ultrafine dust blurs out what otherwise had been an arresting contrast of blues.

“I always carry a protective mask in my bag to wear whenever the ultrafine dust advisories are issued,” she said.

Korea is indeed more dust-shrouded than ever.

|

Students learn how to wear protective masks at Gangseo Elementary School in western Seoul last week. (Yonhap) |

Along with yellow dust from China in spring, ultrafine dust or particulate matter 2.5 ― particles 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter ― have become a major threat to public health.

Last year, the Seoul Metropolitan Government issued ultrafine alerts 11 times, triple the number from the year before, city officials said.

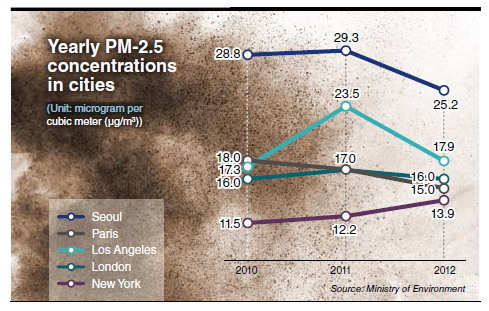

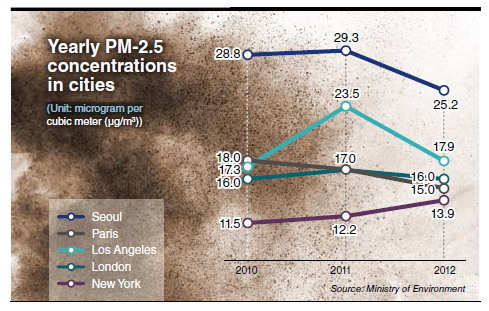

The capital also saw an average ultrafine dust concentration of 25.2 micrograms per cubic meter in 2012, which is more than double the safe level advised by the World Health Organization, according to the Environment Ministry.

In the same year, other major metropolitan cities such as New York, London and Paris reached only around 15 micrograms per cubic meter.

Health concerns are escalating as PM-2.5 can lead to much more serious health problems than other larger particles.

“Ultrafine dust is so small that it not only causes respiratory problems but also enters the circulatory system unlike other types of dust,” said Kim Woon-soo, a senior research fellow at the Seoul Institute.

While China has generally been blamed for the murky air in the case of yellow dust, the significantly lesser-known cause of the ultrafine dust comes from home, experts say.

Recent studies have found that the majority of PM 2.5 here originates from within the peninsula.

In 2013, ultrafine dust from China only accounted for 30 to 50 percent of the total, the government’s data showed. The rest was triggered by local coal-fired power plants and diesel cars.

Ultrafine dust from coal-fired plants

According to Greenpeace East Asia in Seoul, about 60 percent of ultrafine dust came from coal combustion in 2011. Of this, emissions from coal-fired power plants accounted for 3.4 percent.

While the PM 2.5 emission amount from the plants seems minimal, experts noted that other emissions from the power facilities are secondary sources of ultrafine dust.

|

Yeongheung Coal Power Plant in Incheon (Greenpeace) |

“When coal is combusted, nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides are emitted as gases. But the problem is that these gases turn into nitrate and sulphate after chemically reacting with other substances, becoming secondary particles of PM 2.5,” said environmental health professor Lee Jong-tae at Korea University. “It is believed that the secondary ultrafine dust accounts for 20 to 50 percent of the total ultrafine dust.”

According to the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s data in 2009, 41 percent of the ultrafine dust was composed of the secondary products created in the air.

With both the primary and secondary pollutants coming from the coal-fired facilities, Greenpeace has estimated that ultrafine particles could be responsible for up to 1,600 deaths a year.

The death toll could reach 2,800 by 2021 if the government pushes ahead with the construction plan for additional coal-fired power facilities, the global environment organization said.

As of January, Korea has been running 53 coal-fired power stations with a generation capacity of 26,273 megawatts, supporting 40 percent of the nationwide electricity usage.

Having limited options for natural energy sources, the government has mainly relied on coal-fired plants, citing the low-cost and simple operation process.

As part of the state’s electricity supply scheme, 24 additional plants are either under construction or will be built in six years.

“While other countries are putting efforts into reducing the coal usage, the Korean government is anachronously perceiving the situation despite how more people are dying early because of the increasing coal-fired power stations,” claimed Greenpeace campaigner Son Min-woo.

Environmentalists argue that the government should at least tighten the monitoring regulations over the coal-related power stations to protect the public health as well as the environment.

Under Korean environmental law, all facility owners are mandated to keep the emission level of harmful waste under a certain limit. If the limit is exceeded, the facility in question can face a shutdown.

But coal-fired power stations have never been forced to close regardless of the emission level, due to several legal loopholes, the activists said.

According to the Clean Air Conservation Act, the facilities that excessively released pollutants can be exempt from suspension if the punishment is likely to “substantially” impede the livelihood of the country’s residents, national economy and public interest. The Environment Ministry, instead, imposes a fine up to 200 million won ($178,000).

The decision of whether to shut down the facility solely depends on the authority of provisional governors or city mayors, the Environment Ministry said.

“The current regulation only serves as a special favor for the coal-fired power plants,” campaigner Son said. “The state needs to strengthen the anti-emission rules so that the facilities actually work on reducing releasing pollutants.”

Diesel cars ― another culprit of ultrafine dust While coal is considered one of the main sources of ultrafine dust, vehicles -― diesel cars in particular ― are also known to attribute to the phenomenon.

“Compared to other types of cars, diesel vehicles release much more PM 2.5 and other pollutants such as carbon monoxide or hydrocarbon,” said Korea Environment Institute senior researcher Kang Kwang-kyu.

The Environment Ministry’s recent data showed that diesel cars emit about 30 times more ultrafine dust than other vehicles. The WHO has also confirmed that diesel exhaust fumes can cause cancer.

Acknowledging the health risk, the Environment Ministry and some municipalities have put efforts into reducing the number of diesel cars for a decade while encouraging the diesel vehicle owners to equip the cars with pollutant-reducing devices.

In yet another paradoxical move, however, the government announced last year that it would introduce diesel taxis starting this September in a bid to alleviate financial difficulties of cab companies.

Under the plan, the Transport Ministry will provide fuel subsidies for 10,000 diesel cabs every year. Currently, only LPG taxis drivers are eligible for financial assistance.

“Compared to private vehicles, the driving mileage of cabs is eight to 10 times longer, which means that running one diesel taxi is equivalent to riding eight to 10 cars. In other words, allowing 10,000 diesel cabs will be the same as having pollutants from 80,000 to 100,000 cars with much more PM 2.5,” said Song Sang-seok, secretary-general of Network for Green Transport.

Faced by public concerns over the negative environmental impact, Seoul City said it would not implement the government’s initiative to increase the number of diesel taxis.

The Environment Ministry also said it would tighten the monitoring measures over pollutants from diesel cabs, a move experts derided as being wasteful and ineffective.

“Throughout the past decade, the government injected trillions of won to improve air quality. While one side of the government is attempting to save the environment, the other side is putting those efforts to waste,” Song said.

By Lee Hyun-jeong (

rene@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)

![[Herald Review] 'Gangnam B-Side' combines social realism with masterful suspense, performance](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050072_0.jpg)