A set of bills designed to raise the country’s corporate tax rates failed to pass the parliament during its regular session that ended Wednesday.

The two major parties remained poles apart on the need to increase the rates, which currently range from 10 to 22 percent. Lawmakers of the ruling Saenuri Party, who opposed levying heavier taxes on corporations, were reluctant to deliberate on the bills submitted by legislators of the main opposition New Politics Alliance for Democracy.

The ruling party’s stance is in line with President Park Geun-hye’s adherence to her campaign pledge to expand welfare benefits without raising tax rates. Economic policymakers in her administration have argued that levying heavier taxes on companies could hold them back from increasing investment and thus further hamper economic recovery.

But the discontent is growing among working-class people that the current taxation policy has only increased their burden while letting large profitable firms hoard huge amounts of cash on the back of low corporate tax rates. Public calls for higher corporate taxes erupted early this year after a revised tax settlement scheme resulted in putting an additional burden on most wage earners.

Experts say that now is the time for the administration and rival parties to undertake a serious discussion, from a balanced and long-term viewpoint, on whether and how to collect more taxes from companies.

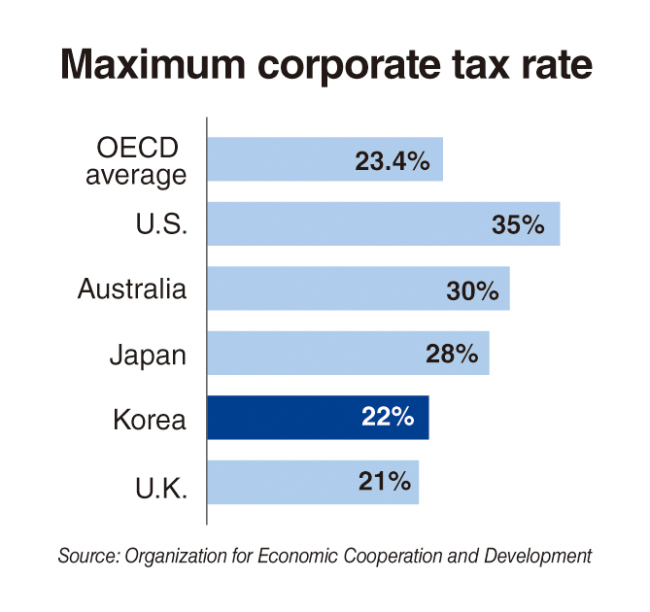

Korea’s corporate tax ceiling has remained unchanged since 2008 when it fell from 25 percent to 22 percent.

The rate is slightly below the 23.4 percent average for the 34-member Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, with corresponding figures standing at 35 percent for the U.S., 30 percent for Australia, 28 percent for Japan and 21 percent for the U.K.

Korea’s ratio of corporate tax revenues to gross domestic product amounted to 3.4 percent in 2013, surpassing the OECD average of 2.9 percent. Corporate tax also accounted for 14 percent of its total tax revenues, the third highest among OECD members.

Noting that the actual tax burdens shouldered by Korean companies are heavier than those for their competitors in other advanced economies, some economists here argue corporate tax rates need to be further cut.

But advocates for corporate tax hikes dismiss the argument as ignoring the fact that the corporate share of GDP and gross national income is far higher in Korea than in other countries.

“Over the past several years, local companies have seen their earnings increase on the back of low corporate tax rates, but the economy still remains sluggish,” said Jeong Sung-hoon, an economics professor at Catholic University of Daegu.

Government data showed taxes collected from wage earners have continued to increase in recent years, while corporate tax revenues decreased from 45.9 trillion won ($41.5 billion) in 2012 to 42.7 trillion won last year.

Jeong, a member of a civic organization campaigning for taxation reform, suggested giving a positive consideration to boosting the economy through an increase in corporate taxes.

A growing number of experts seem to agree that a corporate tax increase cannot indefinitely be excluded from the task of establishing a framework for sustainable welfare spending.

What may complicate their discussion is the difficulty in gauging its effect on tax revenue and corporate investment. Some analysts forecast that raising the rate on corporate profits of more than 50 billion won by 3 percentage points to 25 percent, as proposed by opposition lawmakers, will increase revenue by an annual average 4.6 trillion won over the next five years, while others predict the measure will reduce it by 1.2 trillion won.

Jeong said a modest tax increase might not significantly affect corporate investment plans as big businesses have piled up hundreds of trillions of won in cash reserves.

Experts also emphasize discarding or reducing various tax breaks given to large companies should precede a decision to hike corporate tax rates. They also raise the need to ease quasi-tax burdens on companies. Figures from government agencies and the Korea Employers Federation showed local firms paid 58.6 trillion won in quasi-tax -- including contributions to 95 government-run funds -- last year, with their combined spending on research and development remaining at 43.6 trillion won.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)