[THE INVESTOR] The Investor and The Korea Herald and are jointly publishing a series of in-depth articles analyzing rising business tycoons and their companies’ governance structures. This is the first installment on Kim Seung-youn and Hanwha Group. -- Ed.

Controversies aside, chairman knows a thing or two about mergers and acquisitions

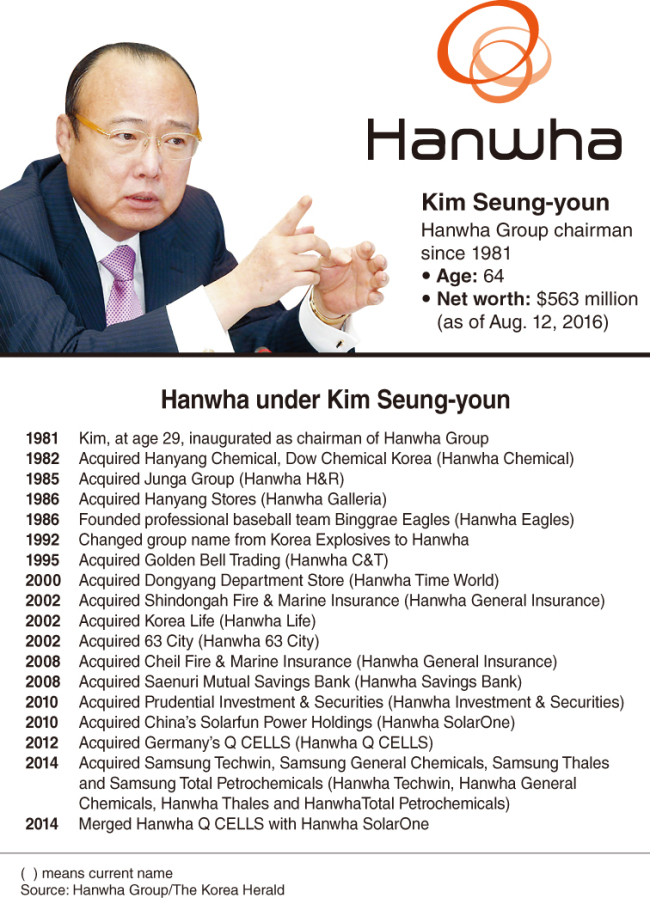

When Hanwha Group announced in late 2014 a 1.9 trillion won ($1.72 billion) deal to buy four assets from Samsung Group, the market sensed the return of Kim Seung-youn, the group’s deal-loving boss who had stayed away from corporate affairs since his conviction of breach of trust two years ago.

The deal, hailed by media as a win-win solution for both sides, was the most fitting comeback for the tycoon whose more than three-decade reign at the group saw its transformation from a gunpowder producer to a hotels-to-finance conglomerate and whose charismatic image was tarnished by scenes of him lying debilitated in a hospital bed inside a courtroom in a thinly-veiled plea for lenience during trial.

With Kim back at its helm, looking just as healthy as before the trial, Hanwha seems to be back on the growth track this year, climbing corporate rankings locally and globally.

“Hanwha seems to be on a roll,” Lee Kwang-ju, a professor emeritus of Dankook University, said in a phone interview. “The chairman has the guts to make bold decisions and the tenacity to stick to them. From the way things look now, he has hit the mark so far.”

Related articles:

Hanwha chairman’s sons in succession race

Looming changes in Hanwha’s governance structure

“Both inherited the businesses from their father and grew them enormously in size. Samsung’s Lee is the winner in this and Kim the runner-up,” he said.

According to Forbes Korea, as of end-2014, under Lee’s 27-year stewardship, Samsung grew 52 times in assets. Kim, who has been at Hanwha’s helm for 33 years, saw the group’s fortunes increase by 48 times.

“While Samsung’s Lee carried on his father’s legacy and sought to gain global competitiveness in the field that his father chose -- semiconductors -- Hanwha’s Kim took his own initiative. He built a business portfolio that looked completely different from his father’s,” Park explained.

“Chairman Kim has his own colors.”

For similar reasons, Lee of Dankook University calls the Hanwha successor “a second founder.”

“Korea’s chaebol tycoons today -- the second or third generation offspring in the founding family -- tend to lean toward risk management. Kim stands out, because he has the traits of a founder -- making bold decisions and enduring pain for a long-term vision,” he said.

"Those traits seem to have translated into acumen in deal-making."

Criticism

Hanwha is not free from the problems of Korea’s chaebol model, which, according to local corporate-governance activists, involves big business groups being run by emperor-like “owners” who come from the founding family, despite their gravely undermined credentials.

With Kim’s charisma and strong drive to push for his vision comes a top-down management style, a lack of checks and balances and other corporate governance breaches, they said.

The most problematic of all is, perhaps, his personal history of legal wrangling.

Kim, during his long tenure as chaebol chief, has undergone five investigations for allegations that include the creation of slush money, the provision of illegal political funds, a violation of foreign exchange rules, abduction and assault.

The chairman was convicted in two of the cases, but in a culture lenient toward law-breaking chaebol chiefs for their “contribution” to the national economy, he was able to continue overseeing the management of Hanwha companies through suspension of imprisonment followed by special pardons.

His biggest ordeal, however, came in 2012 when he received a four-year jail term -- with no strings attached -- for illegally diverting funds from healthy affiliates to weaker companies he owned. After spending four months behind bars and appearing in court as a bedridden patient, he was released for hospitalization due to health concerns. The sentence was then reduced to three years on an appeal and in February 2014 was suspended for five years.

Upon the final verdict, Kim stepped down from seven Hanwha companies where he had held the chief executive’s title, but he has remained as the group’s chairman till now.

“The group chairman is a symbolic post. It has no legal responsibility and receives no payment,” Hanwha’s Lee said.

By law, Kim is barred from taking real positions at Hanwha during his probation period, which ends in February 2019, and for another two years after that.

The group had hoped for a presidential pardon to be granted to Kim. However, he was not included in the beneficiaries of the Aug. 15 amnesty.

“The chairman can’t enroll himself as a registered director, but is back at its management, making key investment decisions like the Samsung deal. This means that he has the power to decide, but bears no legal responsibility for the decisions,” said Solidarity for Economic Reform, a local civic group focusing on corporate governance issues.

“That entails risks for Hanwha’s shareholders.”

By Lee Sun-young/The Korea Herald (milaya@heraldcorp.com)